The auction house’s first attempt to sell NFTs resulted in bad publicity and accusations of ‘cultural vandalism’, all because of a tongue-in-cheek stunt. Dylan Reeve interviews the auction’s creator for IRL.

Earlier this year, Auckland auction house Webb’s dipped its toes into the cyber-waters with its first NFT auction. It was the first local auction house to do it, and the people behind it were hoping to grab attention with the sale of two NFTs of century-old photographs of New Zealand painter CF Goldie.

They certainly did grab attention, but perhaps not quite how they imagined.

Some described the Webb’s auction as “cultural vandalism”. It wasn’t the NFTs themselves that were the problem, but a decision the company made about what to package alongside the digital collectables.

“Look, put it this way, if I had known that it would have resulted in you, Dylan, from The Spinoff, contacting me like this, I wouldn’t have done it,” Charles Ninow, Webb’s director of art, told me as we sat together in the company’s meeting room surrounded by impressive art and collectables.

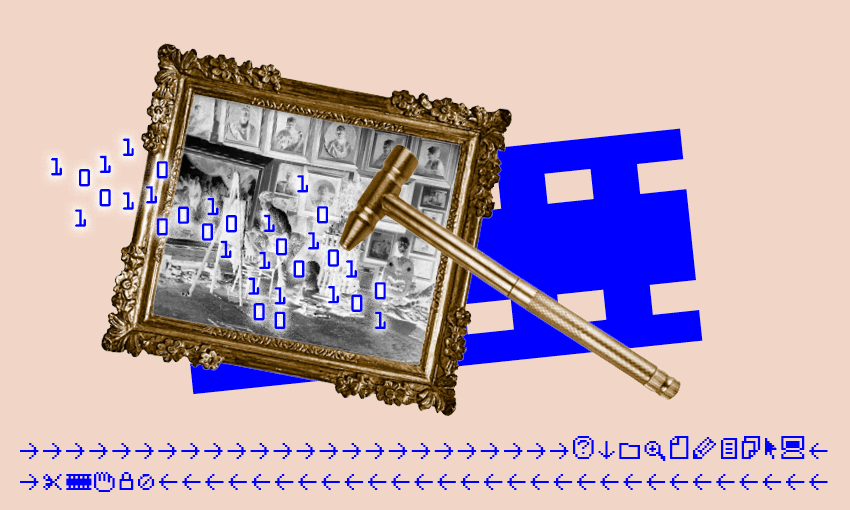

The “it” in question was the not-entirely-explicit suggestion that the 100-year-old glass negatives included in the sale should be destroyed by the winning bidder. It was an implication made by Webb’s opting to include a small brass hammer in the auction – exactly the sort you might use to smash a century-old glass photographic plate.

Ninow did himself no favours when, in a Newshub interview, he addressed the hammer by saying, “Perhaps you might like to make it permanently digital.” Newshub reporter Simon Shepherd went straight for the unspoken implication: “Smash it?”

“Smash it,” said Ninow, with a wry smile and a shrug.

This caused outrage among a select group of art fans online, and even attracted international attention. It was that reaction that got me interested in the auction, and led me to be sitting down with Ninow.

Webb’s historic NFT sale was a hybrid offering, mixing the digital and physical in a single auction. There were two lots on offer, each consisting of an NFT of a black-and-white photograph of acclaimed New Zealand painter C. F. Goldie at work in his studio, along with a high-quality framed print of the same image, and the original glass negative. The negatives were, perhaps, especially significant as they were physical artefacts that had been present more than a century earlier in the camera that took the historically significant photographs.

And there was, of course, the hammer.

Looking back on it, a short while after the two NFTs (and associated physical manifestations) sold to a single bidder for an expectation-defying $127,500, Ninow seemed slightly regretful about what he suggested was supposed to be a playful nod to the emerging digital future. “It didn’t rely on the hammer. It didn’t need to be there.”

Indeed, the hammer wasn’t actually there in the end. It was quietly removed from each lot in the listing, and no hammers were included among the final sold items.

Ninow and I spent more than an hour discussing NFTs and the esoteric nature of art when I visited the Webb’s showroom. He’s an enthusiastic believer in the potential of crypto technology to deliver for artists and collectors and, being anchored mostly among the world of physical art, he is excited about finding ways to merge the digital and physical.

For many people, the first time they heard the term “NFT” was in global news coverage about a record-breaking digital art sale that saw famed auction house Christie’s sell an NFT of ‘Everydays: the First 5000 Days’ by prolific digital artist Beeple for a staggering US$69 million almost exactly a year ago.

NFTs are a well-established concept in the mainstream now, with stories appearing regularly about new ventures, big sales, scams and strange parties. The inbox of any journalist who writes about technology is routinely filled with PR-company pitches for new NFT and crypto products. Companies promoting new NFT offerings have to do something to stand out; somehow make their new cyber-offering unique and special. For Webb’s, that was a number of things: the hybrid nature of the auction, the historic nature of the images.

And the hammer.

“I’ve spoken a lot to people about NFTs in relation to the age of mechanical reproduction, and so it was only meant to further illustrate those ideas,” Ninow tried to explain.

“So it was a metaphorical hammer?” I queried.

“Yes, yeah, well, no,” Ninow paused. “Look, maybe the idea was just overcooked.”

While the NFTs sold by Webb’s went for well above the listed estimates, the final numbers involved weren’t enough to pull in the attention of the world’s media. Unlike Christie’s massive Beeple sale, which allowed bidding in various cryptocurrencies, the Webb’s auction terms are a little more traditional, requiring payment in NZD by direct transfer, EFTPOS or credit card – although Ninow says the company was negotiable on the matter. “If the buyer had wanted to pay in crypto, we would have accepted crypto,” he said.

For Ninow, the opportunity to merge the worlds of digital and traditional art is what’s most appealing at the moment. At a time when talk of NFTs so frequently revolves around procedurally-generated pictures of apes and 3D rabbits, Ninow wants to find ways to tie the online and physical words together.

Despite attracting some online rage, Webb’s first foray into the world of NFTs was a success, according to Ninow, and it definitely won’t be the last. “I can’t say yet what they are, but I’ve got lots of very interesting plans,” Ninow said confidently. “The most important thing for us is that we want to do things that are culturally meaningful and, I think, mean things for the future.”

“But absolutely no more brass hammers,” he added resolutely, having clearly taken on board at least that key lesson from NFT auction number one.