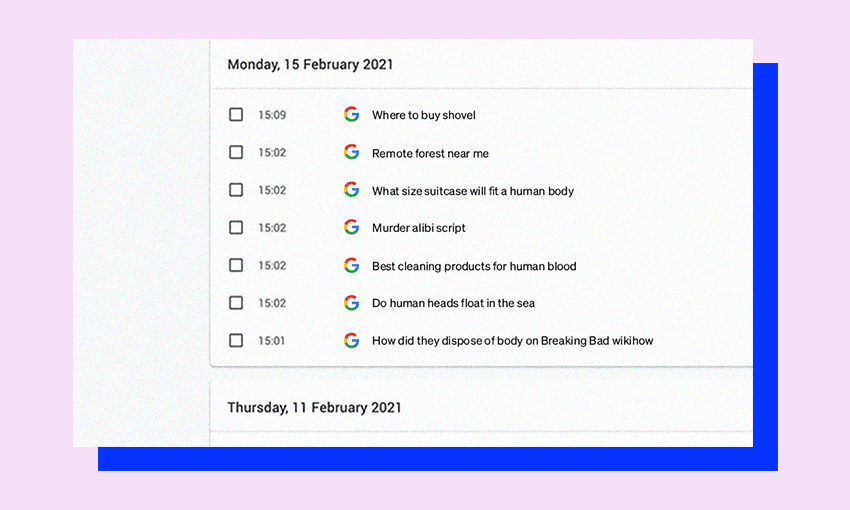

Loath as we are to assist killers, it has to be said: there is no such thing as private browsing when it comes to hiding your crime.

It’s hard to get away with murder these days.

Back in the good old days, you could simply escape justice by hopping on a passenger steamer to the other side of the Atlantic, changing your name, and reinventing yourself as a shady antiques dealer with a mysterious past. Not so in 2024. Even a genius like Agatha Christie would be hard-pressed to come up with an ingenious plot that could survive the rigours of contemporary forensic investigation. Most contemporary detective fiction writers have to go to great lengths to level the playing field for their criminals, such as setting their novels in the first world war, or during a major snowstorm in a remote hotel without any cellphone coverage.

There have been many important advances in forensic investigation since fingerprints were first used as evidence in 1892. DNA evidence has been used in court since the late 1980s. But fingerprints pale in comparison to the astonishingly vast digital footprint each and every one of us leaves behind.

Recently, I watched The Lie: The Murder of Grace Millane. The documentary is harrowing, especially the CCTV footage. But Kempson’s Google searches after the murder are either the work of a complete moron or someone who doesn’t understand how the internet works. Not only did Kempson take photographs of Millane’s body and watch pornography on his phone, but his Google searches following the murder included the terms: “Waitakere ranges,” “The hottest fire,” “large bags near me,” “rigor mortis,” and “flesh eating birds.”

Obviously someone who decided to Google “are there vultures in New Zealand” as a potential cover-up strategy is not the sharpest tool in the shed. While I’m happy that these murders aren’t going unpunished, I feel like this is such a common trend that it calls into question our collective digital illiteracy.

Kempson is not alone in his ignorance. Perhaps the most famous recent instance of someone’s search history being used to convict them of murder was the case of Brian Walshe, who has been indicted for the murder of his wife Ana Walshe, whose body remains missing. Walshe’s search history following his wife’s disappearance included:

4:55 am – How long before a body starts to smell

4:58 am – How to stop a body from decomposing

5:47 am – 10 ways to dispose of a dead body if you really need to

6:25 am – How long for someone to be missing to inherit

6:34 am – Can you throw away body parts

9:29 am – What does formaldehyde do

9:34 am – How long does DNA last

9:59 am – Can identification be made on partial remains

11:34 am – Dismemberment and the best ways to dispose of a body

11:44 am – How to clean blood from wooden floor

11:56 am – Luminol to detect blood

1:08 pm – What happens when you put body parts in ammonia

1:21 pm – Is it better to put crime scene clothes away or wash them

12:45 pm – Hacksaw best tool to dismember

1:10 pm – Can you be charged with murder without a body

1:14 pm – Can you identify a body with broken teeth

1:02 pm – What happens to hair on a dead body

1:13 pm – What is the rate of decomposition of a body found in a plastic bag compared to on a surface in the woods

1:20 pm – Can baking soda mask or make a body smell good?

Jesus Christ.

Walshe made the searches on his son’s iPad, but appears to have made no other attempts to delete his search history. Not that that would have helped.

Usually, I’d be loath to publish anything that could give potential murderers a heads-up. But the truth is that almost nothing you do on the internet is private. At least, not in the context of a murder investigation. There is no amount of digital cleanup you can do that will fully eradicate your suspicious searches and deleted emails from being recovered by a digital forensics team. Not only is it extremely difficult to hide your online activity, anyone who doesn’t have an advanced knowledge of digital forensic techniques isn’t even going to know what to hide, beyond the basics. In order to get away with it, you would have to be smarter than the smartest person whose job it is to scour your online activity for incriminating information, which is an extremely high bar, considering most people still don’t know how to uninstall Bing from their family computers.

Of course, the ability of the police to find digital evidence doesn’t always lead to a conviction.

Casey Anthony was found not guilty of the murder of her daughter, despite searching for information relating to the manufacture of chloroform. Anthony claimed she’d intended to search for “how to make chlorophyll,” despite being physically unable to photosynthesise sunlight. And human error is always a factor. CBS news reported that the digital forensics team in the Anthony case overlooked a search for “fool-proof” suffocation methods.

As I write this, Philip Polkinghorne has just been acquitted of his wife’s murder. Perhaps the most suggestive pieces of evidence in the case were Polkinhorne’s deleted internet searches which were shared in court, including his search for “leg edema after strangulation” the day after Pauline Hanna’s death. But although Polkinghorne deleted his WhatsApp history, searched for how to delete his iCloud history, deleted his searches for how to delete his searches, put his phone into flight mode, and used DuckDuckGo (a more secure browser), whether or not you believe he is guilty, his actions still demonstrate a profound ignorance about how the internet works.

We all know – or really should know – incognito mode isn’t really incognito. The point of using incognito mode is to search for “sexy beautiful naked ladies” and other terms you don’t want popping up in your browser history or autocomplete. But even if you follow Polkinghorne’s example and try to practise good digital hygiene, your methods are unlikely to confound the experts. It’s no good throwing your laptop into the nearest peat bog, because your internet history lives on the cloud, not just your hard drive. Even if you use TOR, a VPN and a secure browser, the information doesn’t just vanish. And downloading TOR or looking up “how to delete search history” after committing a crime is highly suspicious behaviour that will almost certainly raise a few investigative eyebrows.

Even if you use a burner phone, you can be caught. Rex Heuerman, known as the Long Island serial killer, was eventually discovered due to a DNA-covered pizza crust. But the location and pattern of his burner phones in proximity to local cellphone towers and Heuerman’s personal phone was enough for police to prove his guilt. They managed to uncover a staggering amount of incriminating evidence linked to these phones, including frequent searches for “why could law enforcement not trace the calls made by the long island serial killer”, and “why hasn’t the long island serial killer been caught”, “Long Island killer” and “Long Island serial killer phone call”.

Killers of yore only had to worry about eyewitnesses and leaving behind shoe prints. These days, the modern criminal has to contend with CCTV, traffic cameras, ring cameras, browser history, location history, IP addresses, Eftpos transactions and that’s just the tip of the digital iceberg. Many websites that claim not to track you are notorious for tracking you. It doesn’t matter whether you’re logged in as “longislandkiller97” or browsing anonymously. Many websites record not just the obvious stuff, like user accounts and IP addresses, but the size of your computer screen, the settings you have enabled, the time of day you’re online and many other identifying pieces of information which I’m too stupid to understand.

Even if you are a technical mastermind, and for some reason have devoted your life to murder, instead of doing the sensible thing and getting a six-figure job, it’s highly unlikely that any victim of your heinous and reprehensible crimes will have the same levels of data protection in place, and you can expect the police to comprehensively scour their digital histories too.

Private browsing is perfectly serviceable for day-to-day activities you don’t want to share with others using the same computer. But when it comes to covering up evidence of a crime, a good rule of thumb is never google anything you don’t want to be read out and used against you in a court of law one day. Or better yet, don’t kill anyone, you absolute munter.