Which side spent more and why? Jihee Junn crunches the numbers and finds a few misleading claims along the way.

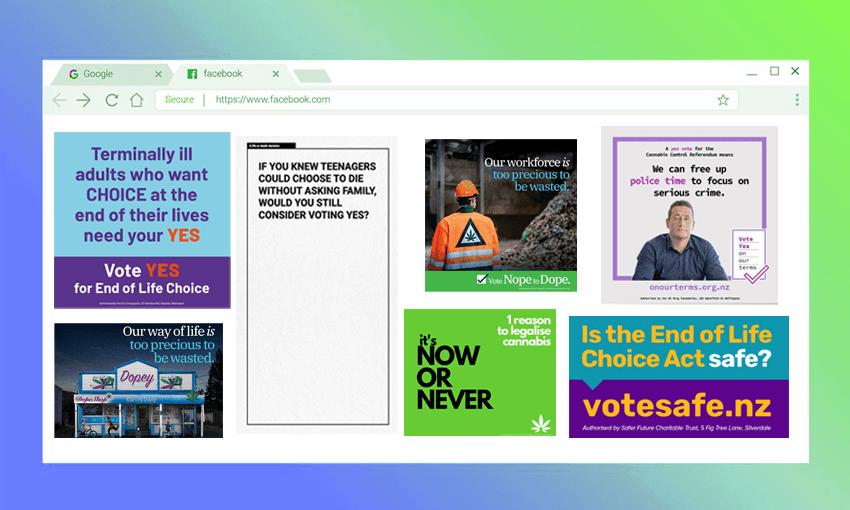

Ahead of election day, a handful of interest groups took to Facebook and Google to lobby for their respective views on the assisted dying and cannabis referendums. In the end, New Zealanders voted decisively for the former and narrowly against the latter. So what, if any, impact did these groups have on the final result? Along with information provided by First Draft, a nonprofit organisation that provides investigative research to newsrooms tracking and reporting on misinformation and disinformation, we break down who spent what, where and why on Facebook (including Instagram) and Google (including YouTube) from August to October.

Note: Data has been taken from August 2 – October 30. Figures are rounded to the nearest $100 and only groups which spent $10,000 or more during that period have been included.

Cannabis referendum

Make It Legal

The biggest spender on digital advertising overall was Make It Legal, a pro-cannabis legalisation group funded by donations and run by a community of volunteers. While the group spent nothing on Google despite being a verified advertiser, it put $121,000 into advertising on Facebook – the most out of any referendum group and the fifth most out of any political advertiser this year (more than the Act Party but less than the Greens).

From August to October, Make It Legal ran 427 ads which touched on a range of reasons to vote in favour of cannabis legalisation, indicative of an A/B-tested, data-led approach to maximise reach and value for money. But as First Draft points out, some ads used partial-context quotes from public figures and cherry-picked statistics. For example, one ad has Jacinda Ardern quoted as saying: “Personally I’ve never wanted to see people criminalised for cannabis use”, leaving out the second half of her sentence in which she says, “but equally I’ve always been concerned about young people accessing it”. While Ardern has since admitted she voted “yes” in the referendum, she repeatedly refused to take a stance prior to the election saying she wanted New Zealanders to make up their own minds on which way to vote.

Another example First Draft points to is an ad stating 80% of New Zealanders had tried cannabis. More specifically, the data refers to a longitudinal study which found 80% of a 1,265-strong “cohort” who were born around the 1970s had used cannabis by their age of 21. This means the statistics roughly refer to the 1990s instead of the situation in recent years. The point is made clearer in this video ad featuring Professor Joseph Boden, director of the Christchurch Health and Development Study, who also wrote on The Spinoff explaining the research back in June.

NZ Drug Foundation

Supported by donations from its members, government funding, and corporate and private grants, the NZ Drug Foundation is a charity working to prevent and reduce drug-related harm. Recognising that “drugs, legal and illegal, are a part of everyday life experience” for New Zealanders, the group takes a harm reduction approach in all its work and took a pro-cannabis legalisation stance for the referendum.

On Facebook, the group spent $23,200 on 58 ads over the three month period promoting animated explainers on how the law would work and making the most of a series of high profile endorsements for the yes campaign from former prime minister Helen Clark, former drug squad detective Tim McKinnel, and actor Sam Neill. One seemingly innocuous ad urging voters to “change cannabis laws for the better” was flagged by Facebook although it’s unclear why.

Meanwhile, on Google, the group spent $10,400 on 18 paid Google search results. Spending peaked at the end of August, presumably in anticipation of the election at its initial date (September 19), and again in the week of the newly scheduled election date on October 17. In total, the group spent $33,600 advertising online.

Say Nope to Dope

As the name suggests, Say Nope to Dope is a group opposed to legalising “drug use, drug growing and drug dealing at any level”. Affiliated with organisations such as Family First and Smart Approaches to Marijuana (SAM), its “Kia-Ora Dopey” ad attracted plenty of attention over the course of the campaign for implying that cannabis would be available from dairies and sold to children if legalised. However, despite receiving more than 30 complaints, the Advertising Standards Authority ruled there were no grounds to proceed since it “assisted with conveying the advertiser’s view of what cannabis retail outlets may look like and how the New Zealand way of life might change if the bill is passed” and was allowed to stay in print and on Facebook.

In total, Say Nope to Dope spent $31,200 on 39 Facebook ads, several of which, First Draft points out, used statistics out of context. In this ad, the group stated that “30% of drivers who had crashed and died had cannabis in their system” but with no indication as to how much cannabis was present or whether there were other substances. One version of this ad was taken down by Facebook for violating the platform’s advertising policies.

Other ads taken down by Facebook include a quote from a GP stating she’d seen “too many patients with severe mental illness triggered by cannabis use” (the link with mental illness remains debated) and another citing the legality of medicinal cannabis in order to urge users to vote against legalising recreational cannabis (likely taken down for its depiction of smoking).

Assisted dying referendum

Risky Law

Spending $47,200 on 81 ads over a roughly three month period, anti-euthanasia group Risky Law was the second-biggest spender among referendum groups. It was also the eighth biggest spender among political advertisers on Facebook, spending more than Greenpeace ($38,800) on environmental campaigns but less than conspiracists Advance NZ/NZPP ($57,400). Like the latter, Risky Law’s page has since been deleted. It’s unclear why, but it’s repeated policy violations suggest it may have been deleted by Facebook – it had 18 ads removed due to a violation of Facebook’s advertising policies, although 11 reappeared despite the takedown.

One such ad featured frightening and dramatised portrayal of “poor old mum”, petrified and lying in hospital, as she overhears her children discussing “the best thing for everyone”. Another ad incorrectly claimed a person would have no time to change their mind once doctors approved the assisted dying process (the act states that those deemed eligible can change their minds at any time). It also used misleading language in some of its content, using the term “teenager” in one ad to obscure eligibility criteria (only 18 and 19-year-olds would be eligible under the law).

On Google, Risky Law – advertising under the name Vote No to the End Of Life Act Incorporated – spent a further $29,400 for a total online ad spend of $76,600. Spending peaked during the week starting October 4 when polls opened for advanced voting, and while the group ran 59 ads from August to October, 46 of these were removed by Google for policy violations.

According to its website, Risky Law is a non-profit incorporated society made up of 22 members who are “professionally qualified in medicine, hospice and palliative care, nursing, law, disability, ethics, advocacy, and social policy”. Funded by donations from private individuals, Risky Law states it isn’t aligned to any religious, civic or professional organisations.

Votesafe.nz

Also on the opposing side of the assisted dying act is Votesafe.nz (or Safer Future Charitable Trust) which spent $33,600 on Google – the most out of any of the referendum groups. It ran almost 180 paid banners, search results and videos from August to October, eight of which were taken down for breaching Google’s advertising policies. Meanwhile on Facebook, the group spent $14,200 on 154 ads. In total, the group spent approximately $47,800

In contrast to Risky Law’s alarmist and negative campaign, Votesafe.nz opted for a more emotional and slightly less confronting approach highlighting real life stories from those with terminal illness. One video tells the story of Vicki who says in 2011, when she attempted suicide, she would’ve opted for assisted dying. “Had it been available, I wouldn’t be here and I’ve enjoyed so many special times since then. You’re not just voting on a law, you’re voting on whether you should kill someone like me.”

DefendNZ

Promoted by New Zealand’s oldest and largest pro-life organisation, Voice for Life, DefendNZ lobbied against the assisted dying legislation and spent $19,900 on Facebook advertising in its efforts to do so. It ran a total of 81 ads, some of which compared the End of Life Choice Act to other assisted dying laws overseas in an attempt to highlight its flaws.

Former prime minister John Key, who supports the legislation, was also quoted as saying in at least two of its ads: “In every law, you can never cover every situation. There could be someone that’s coerced, there could be someone who makes the wrong call”. While Key’s comment is presented as speculation in response to concerns raised during a Newshub panel discussion, the group somewhat misleadingly takes it an admission that “there will be euthanasia coercion”. The quote also obscures Key’s larger point as he continues on to say that “if you looked across the wider population, the massively overwhelmingly majority will get it right, and if they choose [assisted dying], it will be a very small group and it will be very near the end”.

DefendNZ also ran an ad later taken down by Facebook stating that “1,700 Kiwi doctors have publicly come out and said they will be voting no in the euthanasia referendum”. It likely refers to an open letter signed by thousands of doctors saying they believe assisted dying to be unethical. However, their stance on the referendum isn’t explicitly mentioned in the letter.

Yes for Compassion

On the other end of the spectrum is Yes for Compassion, a non-profit organisation funded by donations with support from a number of prominent public figures including former prime ministers John Key, Helen Clark and Sir Geoffrey Palmer.

In the lead up to the election, the group spent $38,900 on 237 Facebook ads, suggesting a more granular campaign than the one carried out by Risky Law. Yes for Compassion’s campaign also had the benefit of being much more positive – its ads stressed the benefits the legislation would have (or would’ve had) for both families and individuals. For example, Heather, whose husband took his own life because of the “unbearable pain” caused by liver cancer, frequently features in the group’s advertising. The campaign also made use of the “yes” campaign’s numerous high profile endorsements with ads quoting politicians from both Labour and National.

In addition to its Facebook spend, Yes for Compassion was one of just four referendum-related groups to advertise on Google, investing $12,000 into 23 ads – a combination of paid search results and YouTube commercials. In total, the group spent $50,900 on online ads.

Key takeaways

With pro-cannabis and anti-euthanasia groups outspending their counterparts on Google and Facebook, it’s clear that those on the backfoot of the referendums’ expected results made much more of a concerted effort (at least financially) to sway voters in their favour. In total, groups who lobbied for a yes vote on cannabis spent $154,600 on online advertising while just $31,200 was spent by their opposition. Groups who lobbied for a no vote on assisted dying spent $144,300 while just $50,900 was spent by the yes campaign.

Six-figure spending from those in favour of the cannabis legislation seems indicative of the uphill battle the yes vote was forced to climb in order to catch up with the more visceral campaign waged by the opposition. In fact, the no campaign was criticised by cannabis researcher Professor Joseph Boden for creating “a field of misinformation” which made it difficult for to voters to discern what was right and wrong. In end, however, it was too much of a hill for the yes vote to surmount – the final results favoured the no vote by 2.3%.

Sensationalism characterised much of the no campaign for assisted dying with dramatised portrayals and sometimes misleading statements used in ads in order to elicit an emotional response. The campaign also clocked up a record number of transgressions with Facebook and Google removing dozens of ads over the roughly three month period. Ultimately though, their efforts to sway the vote failed: 31.4% more New Zealanders voted to legalise assisted dying which will come into effect from next year.

Read more: NZ’s election, online: What did each party spend – and how effective was it?