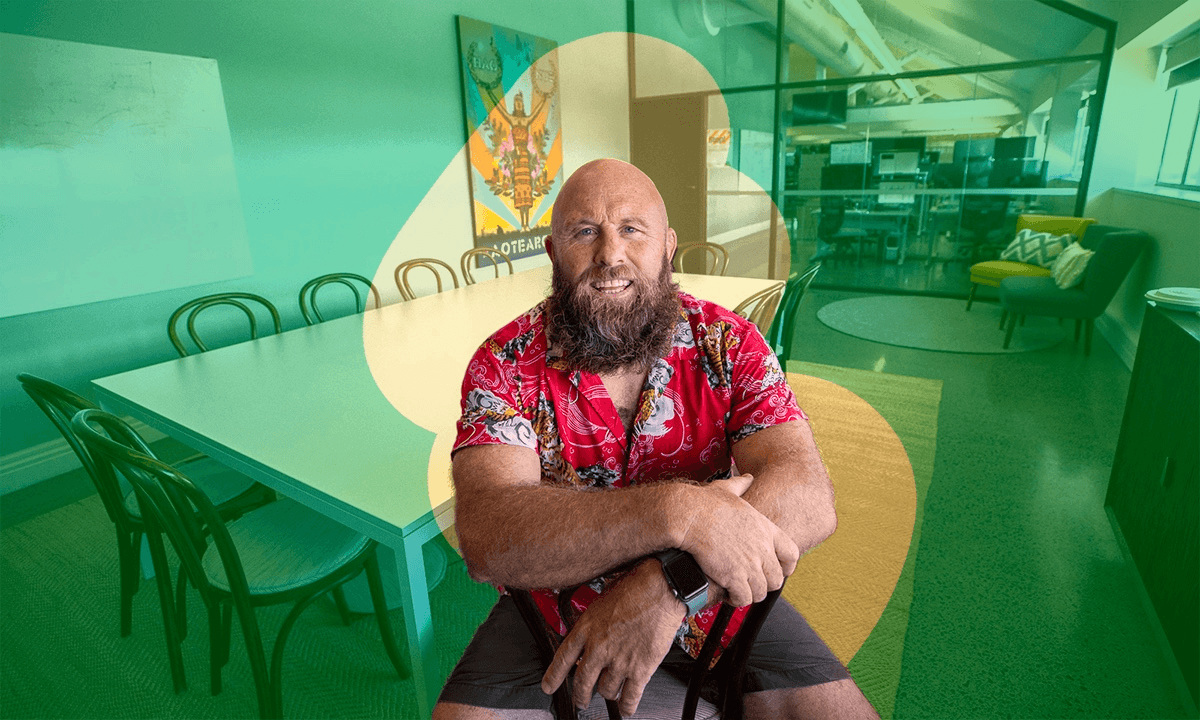

Electric Kiwi wants to lead change in our power market. Ellen Rykers meets the man in charge of making that change happen.

Luke Blincoe doesn’t look like your typical CEO. He’s wearing a short-sleeved patterned shirt and jeans, and says he’s put “longs” on instead of his usual shorts especially for this interview.

I’m flattered that he put on his good pants, especially after he shares a story about visiting Megan Woods, the minister for energy and resources, in Wellington last year. “I was up early, getting dressed, and I was pulling my jeans on, and my partner said, ‘You can’t wear those jeans to the Beehive!’ I was like, ‘OK, I’ll get my tidier jeans.’

“Most days I’ll wear shorts and a T-shirt, but I’ll put on my best jeans to go see the minister.”

Luke has smiling eyes and an impressively bushy beard, which apparently doesn’t require a great deal of maintenance, “except for stealing my partner’s expensive shampoo”. As we sit down to chat in the boardroom of the Electric Kiwi office, overlooking the waterfront in central Auckland, he commits to cut out any swearing.

Blincoe says he fell into the Electric Kiwi CEO role “by accident”. Straight out of university, he got a grad role at PepsiCo when it was owned by Lion Nathan, selling soft drinks to dairies in Hawke’s Bay. Then he moved to massive multinational corporation 3M, maker of Post-It Notes.

For several years he climbed the corporate ladder, until one day he looked around the executive table and noticed everyone was over 60. “I was 36, and I thought, can I do this for 30 more years? There’s no frickin’ way,” he says. He had a young child and wanted to stay put in Aotearoa – and contribute to the country’s future.

So, he shifted into energy – a domestic sector with room to move, which Luke says he found “an intellectual challenge. Eighteen years later, I’m still learning every day,” he says.

His jump to Electric Kiwi came five-and-a-half years ago, when the three founders of the homegrown company recruited him as CEO. The idea behind Electric Kiwi was born over a yarn at a backyard barbecue. Huia Burt, Phil Anderson and Julian Kardos were three high school friends from Whakatāne and they reckoned they could offer New Zealand power consumers more bang their buck and a better deal for the environment.

New Zealand has come to pride itself on our clean green image, bolstered by clean, green, renewable energy. In the OECD, our renewable energy generation of 84% ranks third, behind Iceland and Norway. But on a cold winter’s night when everyone has their heat pumps blasting, electric blankets warming, and dryers spinning, we end up needing to burn fossil fuels to meet demand. (Plus, there’s the issue of market monopolies forcing us into fossil fuel territory – more on that below.) Electric Kiwi figured: couldn’t we engineer a better solution, one that keeps us on the renewable side of things more often?

Blincoe arrived once the fledgling company had attracted around 7,500 customers, and had aspirations to expand. “My final interview was over a quiet beer, at a little corner pub up the road. I said to Phil, “Look, mate, I don’t have a PhD. And if I did, it’d just be in common sense.” And he said, “I think that’s what we need.””

While the founding trio had plenty of technical know-how, Blincoe supercharged the consumer-centric ethos of Electric Kiwi: zeroing in on the wants and needs of customers, and then putting those at the heart of everything the company does. Rather than holing up in a slick corporate office, Blincoe is a CEO of the people – he’s an average bloke, the kind who wears jeans to visit the Beehive. His ability to keep his feet (usually in jandals) firmly on the ground helped the brand resonate with New Zealanders and expand fast. Its base has grown tenfold since Blincoe took the reins, with more than 80,000 customers across the motu.

If people are at the heart, technology is the backbone of everything at Electric Kiwi. They build their own software, which enabled them to commercialise a mainstream product based on smart meters. By 2016, smart meters were installed in around 70% of New Zealanders’ homes – and nearly everyone has one now. Your traditional electricity meter was read once a quarter, but smart meters capture usage data every half-hour and send it remotely to retailers, removing the need for in-person meter readings. But most retailers weren’t smart enough to realise the full potential of the smart tech.

“We can do what we call ‘time-of-use pricing’ – the ‘hour of power’ is a good example. We actually know when people have used the energy so we can give them a different price for different times of the day,” Blincoe explains. This incentivises people to use electricity when the grid is more likely to be running greener, enabling decarbonisation.

That’s another part of the Electric Kiwi ethos. They’re big on actually doing stuff to reduce emissions happening in the first place – rather than purchasing carbon offsets once greenhouse gases are already in the atmosphere. “It’s really about giving people an opportunity to take action, not to buy a clear conscience,” says Blincoe. “Buy carbon offsets and someone somewhere else on the other side of the world might plant a tree? That’s not going to change anything.” Relying solely on offsetting to achieve carbon neutrality is better than nothing, for sure, but not burning coal is way better, he says.

Blincoe also reckons that complacency is “one of our biggest risks to decarbonisation” here in Aotearoa. He sees us as prone to relying on our 84% renewable energy credentials, and as a result we’re just not that motivated to take the last few steps away from fossil fuels.

According to Blincoe, part of the challenge comes from what he describes as New Zealand’s “dysfunctional electricity market”, where a group of big players create a massive imbalance in market power. These are companies that generate electricity – think big hydropower schemes or coal plants – and then sell both on the wholesale and retail markets.

“They control such a significant amount of New Zealand’s electricity storage, which gives them the opportunity to influence prices more than 90% of the time,” Blincoe explains.

Therefore these so-called gentailers have an incentive to always keep electricity supply on the precipice of a shortage, which in turn keeps prices higher. In 2021 a report by Electricity Authority, an independent Crown organisation responsible for regulating the electricity market, expressed concerns that behaviour by the gentailers meant consumers could be paying too much for electricity – and it could be costing households $200 every year.

This is why you see Electric Kiwi in the media calling out “stuff we think is wrong, and we think Kiwis have a right to know,” says Blincoe. Helping New Zealanders understand the impact on them of the market’s flaws and what the solutions look like has become an important part of his role. And he’s not afraid to go into battle for the little man. “I’m the youngest of six kids, so I grew up having to scrap for everything – and that hasn’t changed. I don’t mind having a scrap if I really believe in something.

“This is an important industry for New Zealand’s future from an environmental and economic point of view. It’s an industry that New Zealand needs to get right. And if we can help by shining some light on some things that would otherwise be kept in the dark, we’re not afraid to do it.”

Ultimately, the “dysfunctional electricity market” needs decision-makers to step in and break up the monopoly. “It’s no different really to what the government did in breaking up Spark, back when it was Telecom,” he says. “Look at us now, consumers have benefitted massively. Cross-subsidisation doesn’t serve consumers well.”

Blincoe wants Electric Kiwi to play the role of your friend who tells it like it is – cutting through the opaque web of corporate-speak to tell an uncomplicated story. It’s a fight that he is happy to take on as an average-bloke-turned-CEO, storyteller and champion of underdog energy start-ups. But at its heart, his mission is driven by a deep-seated duty to secure a safe future for his four kids, aged between 10 and 21.

It’s home life that keeps him motivated, but also grounded in what’s really important. For Blincoe, that’s “all the usual kind of family stuff”, like coaching his son’s rugby team, or walking his two Labradors, Colin and Roger. Or spending nearly every weekend at the beach with a surfboard tucked under his arm.

“You get out in the ocean and actually have to be in the moment, have to make a decision on the spot, and have to be present. That’s a really healthy thing for me,” he says.

As with many New Zealanders, the ocean has been a constant in Blincoe’s life. He grew up a short walk from the beach on Auckland’s North Shore, and watched his older brothers and sisters surf during summers at Whangamatā and sail on the Hauraki Gulf, naturally following their lead into the sea. “I haven’t grown out of it yet. Over 40 years’ surfing and I’m still average, which is part of the quest isn’t it?” he laughs

The ocean is his place to connect – to our shared big blue backyard, to purpose, and to family – and he’s passing on that love of the sea to his kids. All four of them surf, including his son at university in Dunedin, who braves the frigid southern waters even in winter.

It’s this brave new generation that gives Blincoe hope for our future. “I look at the youth of today and it gives me huge optimism that they are switched on, sensitive and aware – more than our era and certainly more than our parents’ era,” he says.

“But our generation also needs to take responsibility for giving them opportunities to be their best and make a difference.”