In the first episode of The Spinoff’s new monthly podcast, Actually Interesting, Russell Brown explores the world of A.I. and the way it’s already affecting our lives.

Subscribe to Actually Interesting via iTunes or listen on the player below. To download this episode right click and save.

When you hear the words “Artificial Intelligence” your mind might turn to science fiction – a vast army of robots with aspirations to rule over us – but we already experience AI in our lives every day. When Netflix recommends something we might like, Facebook recognises us in a picture or Spotify builds us a playlist, that’s AI at work.

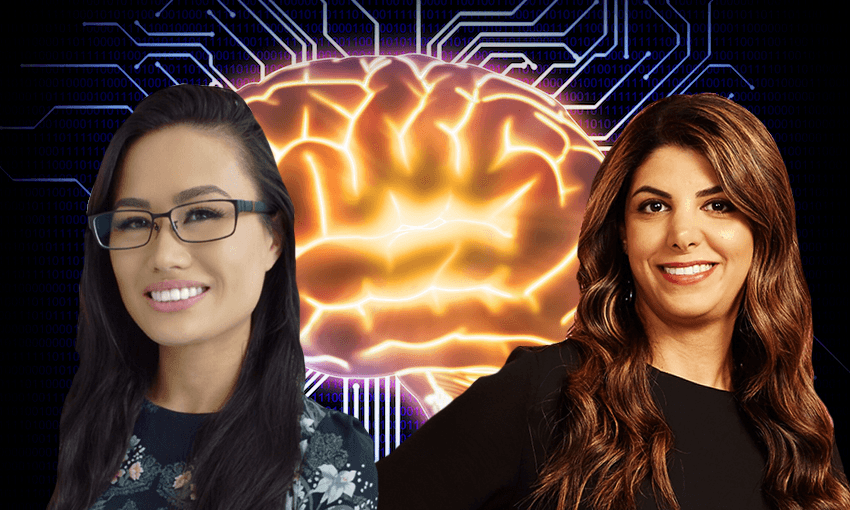

In the first episode of Actually Interesting, brought to you by Microsoft, I talk to AUT’s Mahsa Mohaghegh and Microsoft big data and AI expert Chimene Bonhomme about what AI, algorithms and machine learning actually are – and what they imply for our future.

We also talk about the way that AI works is a product of the assumptions – conscious or unconscious – of the people who design the rules. (That’s what algorithms are: sets of rules.) And the problems that can create when humans are teaching machines about the world.

“Algorithmic bias is the systematic and unfair discrimination or favour towards a certain group,” says Mahsa. “And it’s largely unconscious at the computing level, but in reality, it’s just a reflection of unconscious bias at the development point – or a lack of diversity on development teams.

“Unconscious bias at the human level is coded into the computer system. And one of the easiest ways to tackle it is at the human level. So the more diverse your development team is, you will enter less bias into your dataset.

The same issues are explored – and expanded on by experts in this week’s University of Otago report on government and AI, which focuses on predictive algorithms. The report says that “some degree of input from those most likely to be adversely affected by algorithmic decisions” will be “vital” as official use of this kind of AI expands, and cites research into diversity training.

But Mahsa has a more down-to-earth example:

“A few years back when I was at Google, some friends were telling me a story about the YouTube app. So when they released the YouTube app in iOS and people started uploading video to YouTube, they noticed that a big proportion of the videos were upside-down. So the reason for that is that if you’re right-handed you hold the phone in a way that your camera is up and if you’re left-handed you hold your phone so the camera is down. They didn’t have any left-handed person in the development team, let alone the testing team, to check that!

“Diversity is not only gender diversity, it’s ethnicity, culture, age. So the more diverse your team, the better the performance.”

Chimene – who is “Chinese-Irish-Australian” cited another example: the facial recognition technology at airport border control that instructed one subject to “open your eyes” for scanning. He was, but he was Asian. His eyes were a different shape to those of the faces the machine had been trained on. Yes, it was fixed and no real harm was done. But it could have been fixed before deployment.

AI now does things – facial-recognition included – that only a few years ago some people thought it would never be able to do. It holds extraordinary promise. But we shouldn’t ever forget the simple truth that what you get out of AI is all about the assumptions you put in.

Cultural issues are also entwined in the way AI presents itself. You might have noticed that the voices of digital assistants like Siri and Alexa are almost always female – and, by nature of the job they do, subservient. That was highlighted in a Unesco report last week. One solution: the genderless AI voice.

Chimene says another solution is simply expanding choices: “when I got my new iPhone I changed Siri to an Irish, male voice, because I thought that would be funny.” And maybe she’s onto something. It’s already possible to buy Snoop Dogg as a voice option for in-car GPS systems. Why not go the whole way and have Snoop tell you the weather forecast and the state of the financial markets?

This content was created in paid partnership with Microsoft. Learn more about our partnerships here.