The hearing into the expulsion of Te Pāti Māori MP Mariameno Kapa-Kingi saw lawyers offering their own interpretations of the party’s governing document.

It’s a story most Māori know pretty well by now, the one about the two groups fighting over a document with multiple interpretations. The hearing inside Wellington’s high court on Monday morning challenged Justice Paul Radich to take a “holistic” view in a case of party against party member, where the stakes are higher than just representing the kaupapa. It’s a hearing that also may just decide a political party’s constitution, and its treatment of an MP, is a total dud.

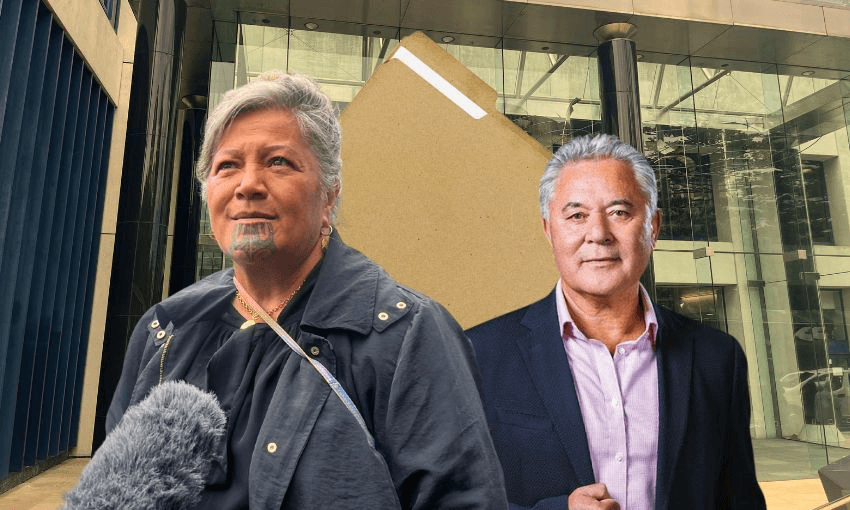

In the case of Mariameno Kapa-Kingi, expelled Te Pāti Māori MP, against John Tamihere, current Te Pāti Māori president, tales of infighting, money troubles and confusing clauses abound. The last time Kapa-Kingi and Tamihere faced off in the high court, during urgent hearings in December, Radich acknowledged “tenable arguments” about “mistaken facts and procedural irregularities” over Kapa-Kingi’s expulsion in November.

Those hearings ended with Radich issuing an interim order for Te Pāti Māori to reinstate Kapa-Kingi as a member. But as of February 2026, Te Pāti Māori have yet to notify the speaker of the House, Gerry Brownlee, of Kapa-Kingi’s reinstatement – in the eyes of parliament, Kapa-Kingi still exists as an independent.

At the heart of the case is the party’s constitution. The 32-page charter uses the terms “cancel”, “expel” and “revoke” pretty much interchangeably, with clause 3.6 allowing the party’s national council (which includes Tamihere) to “cancel” memberships should a number of criteria not be met. These include acting within the party’s constitution and supporting its kaupapa – on the latter, Kapa-Kingi’s lawyer argued, she’s never wavered.

Clause 9 calls for the party’s national council to provide a written notice of expulsions (which, Kapa-Kingi argues, she didn’t receive), and clause 10 rules that those misusing pāti funds “shall be immediately expelled” from the party, and those using funds for personal gain would “have their membership revoked”. Radich mused: “It’s not an easy constitution to follow.”

It’s an “ungainly way to run a party,” lawyer Mike Colson, representative for Kapa-Kingi, told the court of the party’s constitution. The “only serious complaint in the dispute” was the allegation of Kapa-Kingi’s misuse of party funds “for personal gain”, Colson noted. But at the same time that Parliamentary Service alerted Kapa-Kingi’s office to the projected $133,000 overspend in her office, her co-leader’s office was also in a deficit to the tune of $42,286.

Kapa-Kingi couldn’t have misused party funds anyway, Colson argued, as it was funding provided by the Parliamentary Service. As for that personal gain point? Sure, it was going to her son – Eru Kapa-Kingi, who was working in his mother’s office at the time – but he was also an employee receiving pay for the work he did.

“Ultimately, a party created to fight injustice has visited a serious injustice upon one of its own, Ms Kapa-Kingi,” Colson told the court.

After the lunch break, Tamihere’s lawyer Davey Salmon, wearing a salmon-patterned tie, presented his evidence. He argued that despite these words having a “slightly different lean”, taking expel, revoke and cancel to have different meanings within the constitution “plainly wasn’t intended in the drafting of the document”.

And if not a misuse of party funds, how else could one describe what happened in Kapa-Kingi’s office? “Are they seriously saying misusing parliamentary funds is not a [breach] of conduct?” Salmon asked. Did the party intend to mean parliamentary funds as well as party? It’s a “key source” of funding, Salmon argued – there’s no way they couldn’t have meant for it to all mean the same thing. “The most sacred of things is parliamentary expenses,” Salmon told the court.

Salmon urged Radich not to take a “straitjacket view” of the case. The court wasn’t “fit to judge” how the party and its “tough political actors” should have expelled Kapa-Kingi, “because we are not experts in politics and PR”. The “dark arts” of party politics couldn’t be decided by judicial review – “it’s pure contract issues”.

On the legitimacy of Tamihere’s presidency – which Kapa-Kingi is also legally challenging – Salmon argued there was no challenge within the party to remove Tamihere. Despite his three-year term ending in June 2025, Tamihere remains in the role. But there was no complaint and no nomination over Tamihere’s presidency, Salmon said, and the party would have been “rudderless” had it sacked its own president without a replacement. “It’s not like being a mayor where you don’t do much,” Salmon said of Tamihere’s position.

There were efforts made over the summer break by Te Pāti Māori to reinstate Kapa-Kingi as a member, through vote by the party’s national council. According to Salmon, Kapa-Kingi declined the invitation – had she agreed to the vote, she would have had to drop her legal action against Tamihere’s presidency.

The hearing ended just before 5pm on Monday evening, with Salmon noting the “loud ticking of the election clock”. Radich promised the delivery of his verdict would be treated as a real priority – by the time of adjournment, both Tamihere and Kapa-Kingi were long gone, to head off to Northland as Waitangi Day looms.