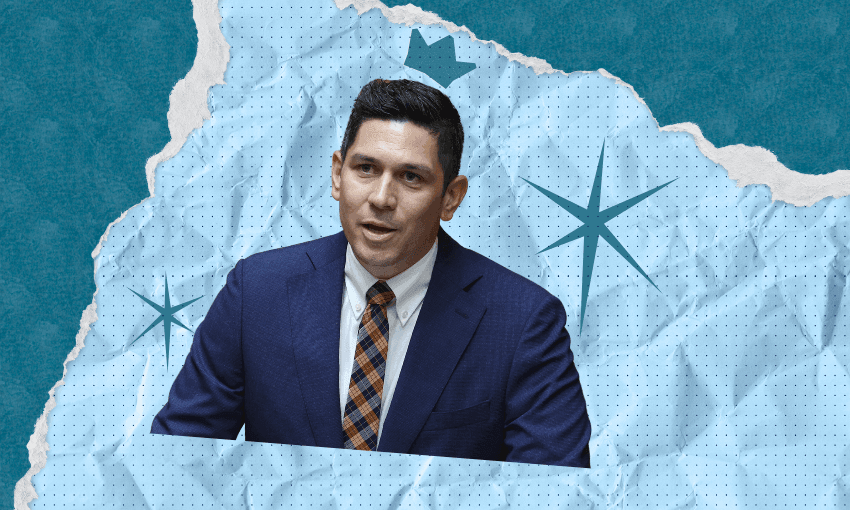

After an acclaimed maiden speech, the new National MP for Rangitata faces his biggest test in politics yet: chairing the committee hearing Act’s controversial bill. He sits down with Toby Manhire to discuss the hearings ahead, and his own path to politics.

Few MPs have such an eventful first 12 months in parliament. A year ago today, James Meager, the National member for the Canterbury seat of Rangitata, kicked off the maiden speeches for the new term in some style. Audrey Young, doyenne of the press gallery, declared it the best debut address she’d seen. “Affecting and uplifting,” it served also to “help lift the fog that has sat over the government since it was formed”, she said.

The stormiest cloud of the new coalition is the 37-year-old former lawyer’s next challenge. As chair of the justice select committee – no small achievement in itself for a first-term MP – he will lead the group tasked with considering and hearing submissions on the Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill, easily the most controversial legislation of the term to date.

It’s a daunting task, logistically and politically: one likely to scale the heights in terms of volume of submissions, rhetorical heat and public scrutiny. Speaking to the Spinoff for a special episode of the podcast Gone By Lunchtime, Meager is careful in his language. The project is “interesting”; the work ahead will be “significant”. As chair, he stresses, he is determined as far as possible to remain above the fray.

It’s a remarkable bill not just because of the tide of indignation it has stirred, most visibly seen in the record-breaking hīkoi to parliament, but its strange status: the prime minister has declared, in language that has steeled over time, that irrespective of what takes place in select committee, it will be voted down on its return to the house. “It will not become law,” Christopher Luxon says.

How do you deal with that? “I think as a select committee we have to treat it as though it will go through the normal process,” Meager said. Part of the process was offering “an opportunity for people to make their views heard and to try and influence members of select committee”.

“Now in this instance, that might be slightly different, because everyone has their positions laid out and they will not change, but it is still, I think, worth having the conversation when it comes before us and treating it with the respect that you treat any other piece of legislation.”

The committee doesn’t just make recommendations for amendments; it also makes a recommendation on whether the bill be passed. “You may want to improve the bill, but the majority of the committee still might determine that they don’t want the bill to pass, or they recommend the house not pass the bill,” he said, adding a cautious: “That could be one outcome of the process, but I can’t preempt it.”

Submissions on the legislation remain open until early January, but one of the early decisions taken by Meager and his committee is to advise that it will not accept contributions containing “racist material, particularly overt racism and characterising people as racist”. That’s quite a call, isn’t it, given that the strongly held view from people with different views in the debate is that they are confronting a racist antagonist? “We’re very much aware of being in favour of people having their views and being as free speech, as far as possible,” said Meager. “But I think there’s a distinction between accusing an individual of being racist and accusing someone’s policies or someone’s ideology of having racist undertones, or, you know, a government policy being racist. I think that stuff will still go through, but it’s once you make direct reflections – ‘person X is a racist, and that’s why they’re putting this bill through’ – that’s the kind of stuff that we don’t really want to see.”

Meager threw together his maiden speech in just a few days, having got a call from the prime minister inviting him to go first, in what is formally cast as a reply to the governor general’s address. And so he “scrambled down a lifetime of thoughts into 15 minutes worth of speaking”. Why did it garner so many accolades? “It managed to just come out in a way which I think reflected who I am and what I stood for, and hopefully managed to find some commonality with people who may not have thought they would have things in common with someone like me,” he said. “Part of my speech was talking about all the stereotypes we make about people in their backgrounds and saying that, you know, it doesn’t really matter who you are or where you come from, it’s the ideas that matter to me. And people who come from very similar places can have very different ideas, and that’s OK.”

In the speech Meager talked about the financial strain on the family growing up, his mum a single parent of three, on a benefit in a state house, making it work against the odds. And he talked about his father. He said: “Dad wasn’t around much growing up and that’s put a strain on our relationship, which has never healed and which may never heal, but I don’t blame him for that. We are products of our upbringing.”

He’d run through the speech with his parents the night before. “My parents have been split since I was very, very little, and I wanted to give them the due respect of telling them what I was going to be saying, and giving them the opportunity to say if they didn’t want that shared. Because ultimately, part of that story was part of their story as well,” he said. “I wanted to try and share that side of my life with the rest of the public as well, and put it out there ahead of anyone else, asking: Where have I come from? What have I done? And what do I deserve to be in this place?”

As for the time since, “Dad’s actually living with me at the moment. So part of our story has almost come full circle, and it’s given us a chance to maybe reconnect and build a more of a father-son relationship. And I am a little bit hesitant about talking too much about it … I was just very thankful that both my parents said that they were proud and were happy for me to share my story. It is what it is.” And, half kidding: “It’s certainly unique to start that therapy in the public eye like this.”

It is not the only complicated part of his own story Meager has laid out in public. In the leadup to the election he told journalist Hamish McNeilly about getting thrown out of his Otago University hall. He was in second year, and he was a bit of an obnoxious dick at the time, by his own admission. He’d tipped a drink over another student and fritzed their computer. “I outlined a lot about some of the mistakes I’d made during my time at university … just to try and demonstrate to people that wer’re all flawed, and we’re all human, and it is a House of Representatives, and if you don’t have people there who have made mistakes in their lives, then you’re probably not going to get anyone there at all.”

It came in the slipstream of the revelations around Sam Uffindell, his boarding school attack on a classmate. Was that in his mind, too, when he decided to front-foot his own skeletons? “I was going through my selection immediately after Sam was going through his issues,” he said. “There was a heightened scrutiny of essentially putting out there anything that you think might be embarrassing to you that has happened throughout your past. It’s a difficult line to draw … how culpable are you for the actions of a 17- or an 18-year-old who is still finding their way in the world and is making sometimes pretty big mistakes? And at what point are you allowed to try and say sorry and have regrets and repair the wrongs of the past and move on?”

Meager decided to “put that all out there” at the time, but it had another function: “For me, it was probably a way of also letting people know what had changed since then. So I haven’t drunk for four-and-a-half years. And that was a professional decision that I made.” He was working as a lawyer before politics and had “come to a realisation that I wasn’t fully in control of my ability to handle alcohol. I think I’d never been taught how to drink responsibly, and so, for me, I made the decision to stop completely.”

Back to the story of his upbringing: a Ngāi Tahu kid in a poor but not impoverished household, single parent, state house, the support of social welfare, his dad toiling away at the freezing works – these are formative years that many might expect to lead into the embrace of leftwing politics. It’s something he took on in that maiden speech. “Members opposite do not own Māori,” he said. “Members opposite do not own the poor. Members opposite do not own the workers. No party and no ideology has a right to claim ownership over anything or anyone.”

But what was it that directed the product of that environment to the centre-right of politics? It’s something he’s mulled over the years. “There’s always been something in me which I think had a bit of skepticism or concern about the role of the state in everyone’s lives, which I understand is ironic because of how much support that we got from, in particular, the welfare system growing up.”

He said: “But I look at what happened when I grew up, and I looked at who made the biggest differences in my life and our lives, and yet we got support from the government when we needed it as a fallback and as a safety net. But ultimately, I don’t think I would be here where I am today if it weren’t for the fact that it really was Mum that made those decisions, and she was the one that was always sort of out there, hustling, trying to get a bit of work here and there, making sure that we were well fed, and that we went to school with book bags and that we did our homework.”

Meager digresses from there into an exhortation on the value of community groups and clubs – if it doesn’t sound like a fully formed philosophy, it comes with a disarmingly frank curiosity. As for being tangata whenua, he said his Māoriness affects his politics “probably very little”.

“Because I struggle with that concept. I struggle with the idea that you can define it as being a certain thing or having a certain essence. We get submissions all the time [at the select committee] where people will say, ‘this is the Māori worldview on x’, or ‘this is what it means to be Māori’. And the reason I struggle with that is because if all of a sudden you don’t fit that criteria, or you feel like that label doesn’t apply to you, does that then mean you’re no longer Maori, or you no longer have that identity?”

He continued: “What is undeniable is whakapapa and ancestry. But what I think people talk about is a cultural sense, or almost a cultural stereotype of what it is to be Māori or to be part of the Māori world. And I struggle with the idea that there is such a thing. To say that you count as a Māori if you believe this, but you don’t count if you believe other things, I think that leads to very, very problematic outcomes.”

What about the hīkoi that brought tens of thousands, Māori and non-Māori, streaming through Wellington? Did that make any special impression, watching from parliament? Not emotionally. He admired that democratic feat of expression, and that “it will have sparked different things in different people” but “nothing in that particular protest sparked anything in me”.

The hikoi culminated after another powerful expression – the debating chamber haka by Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke, viewed more than half a billion times around the world. That unannounced intervention, launched with the ripping in two of a copy of David Seymour’s treaty principles bill, triggered disciplinary action from the speaker. But is there room for haka, say, or waiata, as an expression before the select committee hearing submissions on that same bill?

The committee hadn’t discussed the question, he said. But, “unlike in the debating chamber, there are fewer restrictions on things like waiata and haka and how you want to present your oral submission. So I wouldn’t think we’d put any restrictions on that. I guess the thing they’ve got to toss up when you’re making an oral submission is how do you make that submission in a way which is going to best advocate your position?

“If people want to express themselves like that, I think they they should feel entitled to but I’ve still got to run a process, and I’ve still got to make sure that people who come, if they get 10 minutes, that everyone gets 10 minutes, and so if that’s how they want to use the time, I think that’s entirely up to them.”

Written submissions close on January 7, with oral submissions scheduled to begin in the week of January 27.