It’s pretty confusing on the surface, but if you had 30 hours to spare, you would have learnt a lot about the Regulatory Standards Bill from its week in the select committee.

The finance and expenditure committee’s hearings on the Regulatory Standards Bill (RSB) came to a close on Friday, following four days, 30 hours, 208 submissions and a whole load of takes. Submissions spanned perspectives from the environment and energy sectors to individuals living with disabilities or in poverty. It’s a contentious bill whose name and purpose tends to return puzzled looks, because really, what does it all mean?

There’s been much to say about the public perception of the bill and its many vocal opponents from its architect, deputy prime minister David Seymour. There’s been “so much misinformation” despite it simply setting out a framework for better regulations, Seymour reckoned on Monday, though his accusations of the bill’s opponents having some kind of “derangement syndrome” haven’t really been helpful, either.

Meanwhile, opponents have been campaigning against the bill with the same ferocity shown in the lead up to the justice committee’s hearings on the Treaty principles bill earlier this year. While the emphasis on property and individual rights have raised immediate alarm bells, there’s also a lot of interpretation about what the bill could do, like giving corporations the power to take the government or the little guy to court when they believe their property rights have been impeded on.

Realistically, the truth is somewhere in between. Because elements of the RSB are so vague – its scope, its principles and its purpose – it’s hard to tell what Aotearoa will look like after the bill comes into full force on July 1, 2026. Ideally, this select committee process will take into account the concerns shared by submitters, and shape the bill into something we can visualise a little better.

Until then, here’s everything that I learnt about the bill and its submitters from these hearings:

- If oral submissions are anything to go by, most of the public opposes this bill.

- But there’s also a decent chunk sitting on the fence because, yeah, Aotearoa does need improved regulations, but there’s sufficient doubt that the RSB will actually achieve this.

- Subpart 5 of the RSB clarifies that the bill does not impose legal rights nor does it require compliance. Despite this, many submitters who opposed the bill feared it could give large corporations too much power in the court room, like in the case of Phillip Morris (tobacco) v the Australian government over plain packaging legislation.

- There is a genuine argument that the longer this bill stays in statute, the more influence it could gain over time, and the more likely certain courts may look to its principles as guidelines.

- There’s often a lot of dissonance between the way the courts have interpreted the law and how parliament interprets it.

- If a Phillip Morris v Australia situation played out in Aotearoa because of the RSB, parliament could just draft an amendment to make the bill’s legal restrictions tighter.

- And Seymour can very easily claim no blame for what the courts have done.

- But there’s also the potential of the RSB becoming like the Bill of Rights Act, which is a part of our unwritten constitution but is more-so quasi-constitutional: it’s not entrenched in law, but it’s been around long enough – and has enough influence – to impact on the law-making process.

- There is a genuine case for including the Treaty in the bill. Seymour and the man who dreamt up the bill’s blueprint, Dr Bryce Wilkinson, both claim there’s nothing in the bill that wouldn’t uphold Māori rights, but it’s a bit deeper than that – the principles of responsible regulation just don’t align with a te ao Māori worldview.

- The principles of responsible regulations do need a broader appeal if we want legislation that will actually improve our regulations, not a law that will be chucked out when the next Labour government is elected.

- Only applying the bill’s principles to primary legislation will make this palaver far less of a headache.

- Treating everyone as “equal” under the law is actually not a great way of helping our most vulnerable communities.

- Essentially everything in your life is regulated, from the air you breathe to the clothes you wear and the home you return to every night and what you’re eating when you get there. Maybe this is a pretty juvenile thing to realise at the ripe age of 25, but it’s also not something the layman often thinks about.

- Regulations aren’t necessarily a bad thing, either – they can keep us alive.

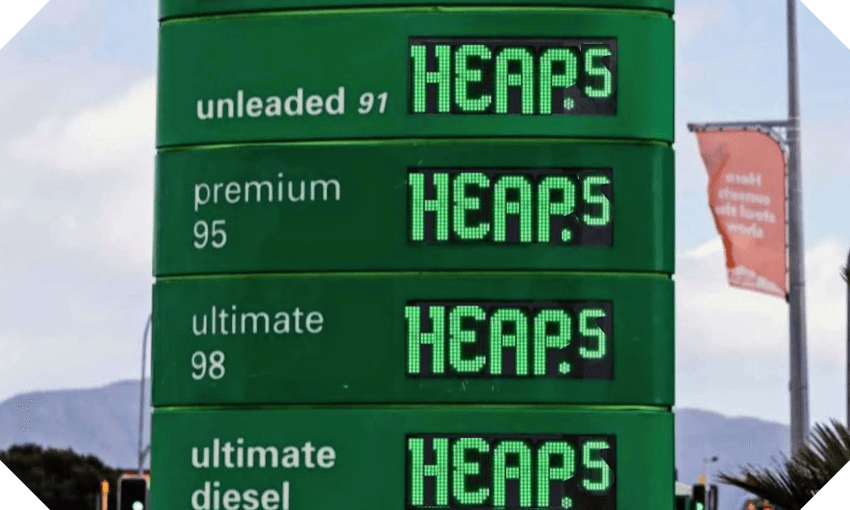

- Certain industries, such as the energy sector, are set to benefit a lot more from the RSB than others.

- Much of what the proposed regulatory standards board will do is already covered by the regulatory review committee.

- The Clerk of the House can submit on bills, and in this parliamentary term the Clerk has submitted in person on three occasions. When deputy clerk Suze Jones showed up to the RSB hearing on Wednesday, Labour’s Deborah Russell (who joined parliament in 2017) claimed it was the first time she had seen the Clerk submit to the select committee in person.

- Geoffrey Palmer likes to be punctual – he showed up an hour early for his submission.

- Russell has a PhD in political theory. And is familiar with Jean Rousseau.

- Donna Huata, founding member of the Act Party, has some shame about what the party has become.

- Most submitters show up just before their allotted speaking time and leave right after, but there was one submitter who stayed for hours to hear multiple perspectives: Tex Edwards, of Monopoly Watch NZ.

- Trickle down economics is like pissing on people and telling them it’s rain.

- Ministers aren’t supposed to attend select committees unless they’re invited, which is why you can’t really blame Seymour for not showing up.

- But, it makes a big difference to a submitter to have the committee actually show up. Holding the RSB hearings in a non-sitting week meant the MPs were all back in their electorates and listening on Zoom, and this didn’t go down smoothly with a few submitters who hoped they could make their case face-to-face.

- You probably won’t get a heads up that no one’s in the room if you’re showing up to parliament to submit, either.

- The online discourse around this bill is already having real life implications, with lawyer Tania Waikato needing a security escort to make her submission at parliament.

- The select committee can play pretty fast and loose with allotted speaking times, like cutting some submissions short, or letting others stretch past their allotted time, as was allowed for the NZ Initiative.

- Even our politicians forget to turn the mute button off/on. It’s not just you.

- The administrative staff who run these hearings are very lovely people. They didn’t have to answer stupid questions from journalists (or a single journalist, aka me) but they did anyway.

- It’s possible for something to have the potential to be both really good, and really bad.