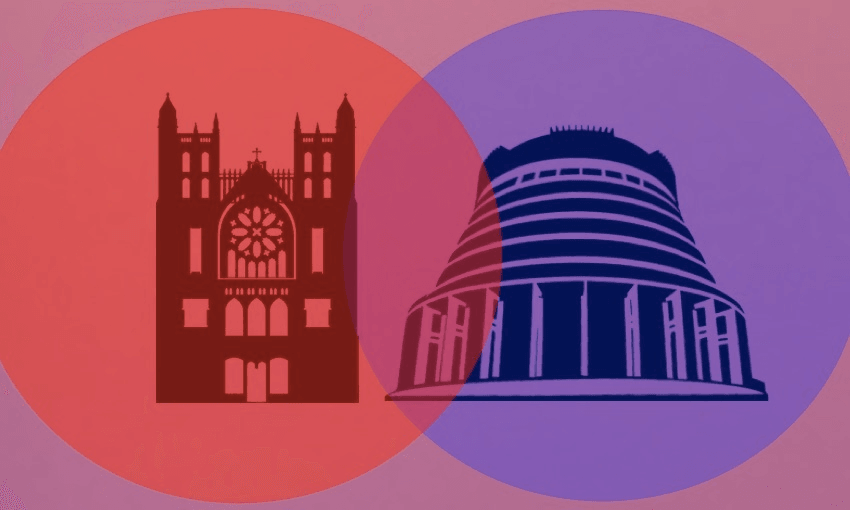

National leader Judith Collins’ newly prominent display of faith is a risky strategy, but, as Marion Maddox writes, that hasn’t stopped her overseas counterparts from giving it a go.

“As a Christian, I do believe in miracles.” Looking at Labour’s recent polling, some might take Judith Collins’ leaders’ debate comment as referring to her own party’s chances.

She certainly echoed Australian prime minister Scott Morrison’s triumphant election-night declaration, after his unexpected 2019 victory: “I have always believed in miracles.”

After asking “God’s blessings” on defeated Labor opposition leader Bill Shorten, Morrison described his wife and daughters as “the three biggest miracles in my life”, adding, “and tonight we’ve been delivered another one” (the election victory).

A further parallel came when Collins was photographed in church before casting her vote, just as Morrison was in the lead-up to Australia’s 2019 federal election. Morrison invited the media into the church, whereas Collins merely “didn’t want to stop” the media coming in, because going to church “is a good thing for everyone”.

Collins and Morrison also share something even more profound: a reluctance to answer questions about how their faith relates to their politics. “That’s between me and God,” Collins replied, when asked what she had prayed about during that pre-poll photo. Morrison similarly insists that his faith is private.

Except when it isn’t, and if it can be snapped in a church. Critics pointed out that Morrison’s calls to the nation to pray for rain during Australia’s recent drought sat oddly with his government’s refusal to develop a climate policy, for example.

Never mind his often-quoted statement that “the Bible is not a policy handbook”. In the case of climate, seemingly, prayer was the policy.

All this religious positioning on the part of leaders of broad-based parties might seem unlikely. After all, both Collins and Morrison address rapidly secularising electorates: New Zealand’s 2018 census found nearly half of respondents (48.2%) claiming “no religion”; the “no religion” figure in Australia’s 2016 census was 30%.

Moreover, those still ticking the various “Christian” boxes cannot, of course, be gathered into a single political bundle, nor yet a theological one. Not all churches “believe in miracles”, in the sense of direct divine intervention in this world’s affairs. At the other extreme, some believe that divinely appointed church leaders, rather than the popularly elected democratic ones, should govern.

But New Zealand’s MMP electoral system, encouraging niche parties, has fostered a succession of conservative Christian or Christian-inflected parties, some of which briefly thrived (remember United Future?). For all the dreams of a unified “Christian vote”, such parties seldom hit the 5% threshold and tend to fragment and fizzle.

The latest, New Conservatives, is unlikely to win seats; but, as Collins warned, might “waste” votes (take them away from National).

Her newly prominent Anglicanism has been widely interpreted as a welcoming signal to voters tempted further right. Collins, who describes herself as a liberal Anglican who only “sometimes” attends church, sees her support for both abortion and legalised euthanasia as “entirely consistent” with her faith; so she won’t find much common ground on the New Conservatives’ culture wars topics.

Instead, religious allusions allow a politician to hark back to a seemingly more settled time when Christians made up a comfortable majority.

It’s a risky strategy. For one thing, it can send a worrying message to those who were never part of that majority.

Take Collins’ assurance that going to church “is a good thing for everyone”. Everyone? What about the 6% of New Zealanders who identify with a religion other than Christianity?

So what’s the alternative? Leaders praying, or dropping religious allusions, often produces calls to “keep religion out of politics”, implying that politicians should self-censor their religious views.

Such a solution seems undemocratic – why should religious people uniquely have to keep out of public debate, or else keep their deepest motivations quiet? Furthermore, putting some motivations (religious ones) out of view and therefore beyond the scope of public debate might even be dangerous. At the very least, telling politicians to keep their religious views quiet seems like telling them they have to be disingenuous or dishonest.

And when religion is treated as ripe for political symbolism, but too private and personal for questioning or debate, it easily lends itself to dog-whistle politics. The extreme version is Donald Trump, happy to brandish a Bible but replying it’s “too personal” when asked to cite a favourite verse. Instead, his Christianity signals white nationalism.

As I’ve argued elsewhere, we should treat religion as we do other aspects of political debate. If leaders want to bring it up, fine. But, having done so, it’s a bit much to then refuse to discuss it further. Just like we ask them to explain other important things such as their economic theories, party ideology, voters should expect them to explain where their religious stance comes from, and how it fits into their politics.

Collins herself did so in relation to abortion and euthanasia. Indeed, in international comparison, New Zealand’s election campaign looks refreshingly civilised. These days, that feels like a miracle.