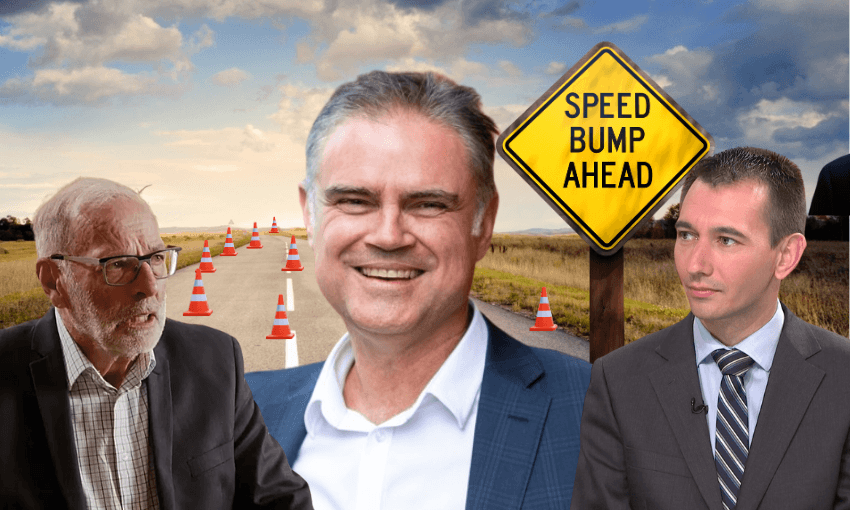

Dean Kimpton thought he was turning Auckland Transport around. Then his political bosses spent a week telling everyone how much it sucks and needs to be put in its place.

Dean Kimpton is definitely hurt, even if he won’t say so. The Auckland Transport chief executive has spent a week watching his political bosses hurl insults at his organisation, telling everyone all the ways it sucks as they move to strip it of all its responsibilities except running public transport.

“Today is a great day for Auckland,” said minister for Auckland Simeon Brown as he fronted a September 5 press conference announcing the imminent defenestration. “Aucklanders have become sick and tired of decisions being made in regards to their transport policies, their roading corridors, without their direct involvement.” Auckland mayor Wayne Brown followed suit. “Auckland Transport are not accountable in the same way as elected officials. You can’t vote out faceless bureaucrats,” he said, in an honestly excellently produced social media video which his team should be proud of.

In an interview in a plain corner office by his standing desk on the fourth floor of AT’s Fanshawe Street headquarters, Kimpton seems slightly baffled by the onslaught. He took over as chief executive two years ago, when AT’s reputation was in the toilet. Progressives were mad at it for squandering years of political support for decisive change. They accused it of surrendering to cycleway haters and dragging its feet on reallocating road space away from cars. Conservatives were pissed for pretty much the opposite reasons. They accused the organisation of lowering speed limits and scattering concrete humps around willy nilly without any regard for car-loving community views.

Kimpton thought he’d charted a path between the two camps, coming up with compromises that would make everyone a little less steamed. “I’m proud of what this organisation has achieved,” he says. “We’ve knocked out of the park a significant amount of things, all of which we’ve agreed with the council that we need to focus on and deliver.” Now the politicians were acting like none of that happened. “Despite my very clear frustrations, expressed by myself and the public, AT have failed to change their ways,” said Brown (Wayne) in his really quite expertly put-together video. “They haven’t listened and they haven’t had to.”

Obviously, Kimpton doesn’t agree. He can point to a list of stats that suggest AT has been making an effort to turn things around. Though the mayor probably isn’t among their number, the number of customers who say the organisation listens and responds has risen from 23% two years ago to 36% in the last result; still in the toilet, but no longer most of the way to the Māngere Oxidation Ponds.

When it comes to relationships with local boards, the figures are more impressive, with satisfaction rising from 41% to 78%. Kimpton attributes that in part to a new approach he’s implemented, which boils down to “if they don’t want it, don’t build it”. AT will present the evidence for interventions like lower speed limits or bike lanes, but if a board rejects its advice, it will move on to the next one. “There is far more demand for those improvements than there is money available,” he says. “So if one board doesn’t want to move on it, there’s five other improvement projects we can go to.”

Kimpton thinks the politicians are abolishing the AT that was, rather than the one that exists today, and immediately after the two Browns held their press conference putting the organisation on blast, he went out and told his staff as much. “This is about the politics of transport, not the performance of the entity I know,” he says. “And people will yell back at me on this one, saying, ‘you haven’t done this and haven’t done that and haven’t done the other thing’, but we implemented all the speed changes the government wanted. We have reviewed how we deliver raised pedestrian crossings. We have fixed up the potholes. We’ve fixed a lot of the things that really annoyed Aucklanders, but there was this legacy that we can never resolve.”

The Browns clearly didn’t think the agency, and Kimpton, had done enough, and AT is now in a wind-down phase. The government’s bill stripping it of most of its powers will likely pass in March next year, after which there will be a six-month handover period. Kimpton won’t say whether he’s going to resign, only that he’s considering his future. “The current role of chief executive for Auckland Transport has fundamentally changed,” he says.

Still, he’s at pains to insist he wants to hand over a “high-performing” organisation to the council. Why though? His political bosses have almost gone out of their way to be as insulting as possible. Isn’t there at least a temptation to check out, kick back and wait for the end? “It might be a personality defect,” he says, before expanding a little. “I’m not a narcissist. I actually believe in what we’re trying to achieve here. So yeah, they’ve made a decision, and whether I think it’s right or wrong is not material. What is material is how I behave and what I do with it.”

All that sounds pretty honourable, but if you listen closely you can also hear a hint of schadenfreude in the background to some of his comments. AT has spent 15 years getting hammered from all sides. It sits outside the tent, trying to balance the demands of the council, local boards and the government – which Kimpton points out are often contradictory, and in some cases completely or partially unfunded.

Politicians criticise it constantly, even when it’s implementing strategies they voted for. Soon those same politicians won’t be able to divert people’s ire to the big bureaucratic blame sponge down the road. They may actually have to be accountable for their own actions. “They’ll have to own the outcome, and that’s what the people of Auckland have been asking for, and that’s what the governing body has been asking for,” says Kimpton.

If he takes some pleasure at someone else finally sitting in the hot seat, he won’t say. Two years as the chief executive of one of the nation’s most hated organisations has given him a good bureaucratic poker face. But when asked to comment on the difficulty of pleasing everybody, even when they want completely different things, he can’t help but smile thinly.

“That dilemma now sits with Auckland Council,” he says.