How a Trumpian beef about interest rates spilled over to New Zealand.

When the ancient Roman Republic was facing a crisis such as a war or internal rebellion, the senate could temporarily appoint a single leader with near-absolute power. Their title was dictator.

It was widely accepted that in an emergency, one person could take action faster and more effectively than following the usual process of senate debates and legislation. Dictators got things done. But the downsides were clear: absolute power corrupts absolutely. When one person controls everything, they can destroy a nation with their own selfish desires.

That’s why most modern democracies emphasise the importance of checks and balances and the separation of powers. That can come with inefficiency and inaction, but it reduces downside risk.

That’s especially important when it comes to monetary policy. Politicians always want low interest rates because it leads to short-term growth. House prices go up, unemployment goes down, and people feel richer. When politicians have total control, they have an incentive to over-egg the money supply, leading to inflation and severe long-term consequences.

To prevent this, most modern nations developed the norm of central bank independence. The people responsible for creating money shouldn’t base decisions on their re-election chances.

The United States has historically had a major focus on separation of powers between the various branches of government – and especially the Federal Reserve, the equivalent of New Zealand’s Reserve Bank. Under President Donald Trump, that is changing. With effective control of the Supreme Court and both houses of congress, Trump has consolidated an extraordinary amount of power in the presidency – as shown by the recent military action in Venezuela to arrest dictator Nicolás Maduro without congressional approval.

Now, Trump has set his sights on the Fed. He’s made it abundantly clear that he wants Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell to cut interest rates further, but Powell is wary that further cuts could lead to inflation.

Christopher Luxon’s re-election strategy is similarly based around lower interest rates. He, too, has been accused of undermining reserve bank independence by sharing his “reckons” with the bank before OCR announcements.

Earlier this week, US federal prosecutors opened a criminal investigation into Powell. Ostensibly, it was about cost blowouts during renovations to the Federal Reserve’s Washington D.C. offices, but many observers have called it out for what it is: a barely-concealed attempt to pressure Powell into doing his bidding – or set the stage for him to fire Powell and replace him with a patsy.

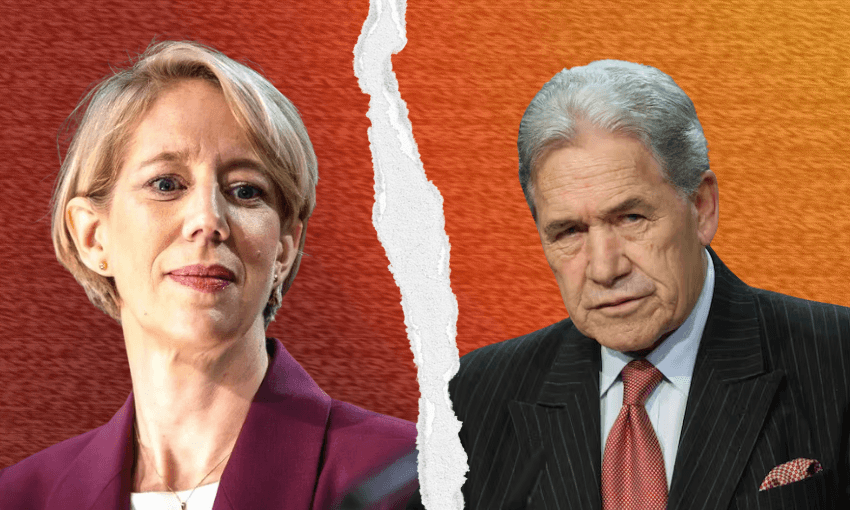

In response, 14 central bankers signed a joint letter offering “full solidarity” to Powell and emphasising the importance of independent banks – including New Zealand’s newly appointed Reserve Bank governor Anna Breman. This set off yet another power struggle, this time between herself and foreign minister Winston Peters.

In the past, Peters has been a proud champion of reserve bank independence. But in this instance, he admonished Breman for speaking out – literally telling her to “stay in her lane”.

There are a few ways to read this. It could be that Peters is especially nervous about Trump lashing out at New Zealand. It could be that he secretly approves of Trump’s decision. But it’s most likely that this is about personal power.

Peters has jealously protected his role as foreign minister. He doesn’t like anyone stepping on his turf. He gave David Seymour a public telling off for “talking out of his field” on Palestine, and has repeatedly rebuked Luxon for talking about tariffs and trade deals without his sign-off.

However, in telling Breman to stay in her lane, Peters has made the line of reserve bank independence blurrier. Breman could fairly argue that the letter wasn’t all that controversial – she’s a central banker commenting on central banking policy, and the letter mostly just emphasises the well-established position that central bank independence is important.

For Breman, it was a minor gaffe. She – or one of her advisors – should have known that Peters would throw his toys if she signed the letter without consulting him. The bigger miscalculation may have come from the European central bankers who wrote the letter in the first place. The disapproval of globalist bankers is hardly something that scares the Trump administration. It’ll just embolden them further.

As Trump unapologetically tramples upon the international rules-based order, liberal opponents often sound like esoteric process nerds. Voters want the government to get stuff done, they don’t know or care how it happens.

While most voters may not be paying attention, the market certainly is. Investors are spooked by Trump’s actions, afraid that he will trigger further inflation or some other chaos. Gold and silver, two assets which are popular at times of uncertainty, both hit record highs this month.