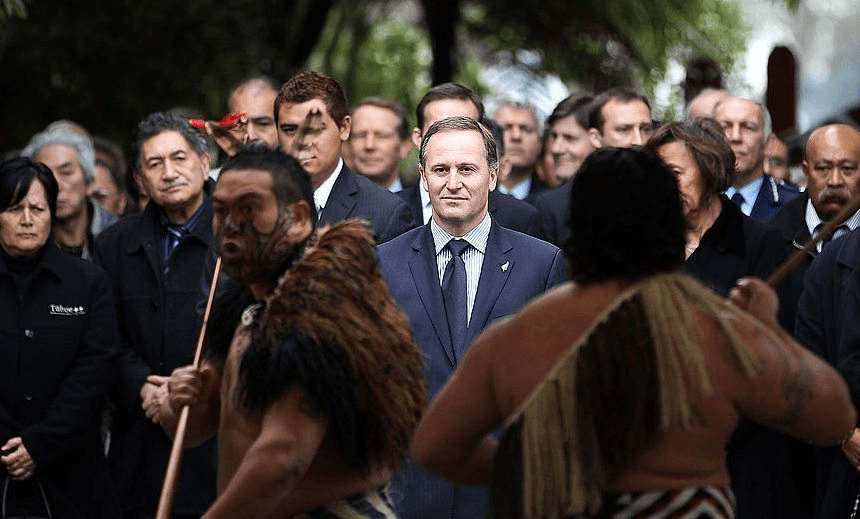

Under Prime Minister Key and settlements minister Chris Finlayson deeds of settlement have been finalised with nearly 50 Māori groups. That’s an impressive number, but the drive to reach deals may have been overhasty, argues Ngāi Tahu Research Centre lecturer Martin Fisher.

As New Zealand adjusted to the idea of one of its most popular prime ministers resigning, discussions began about his legacy. While a tight selfie game is certainly an asset in our current political climate, the questions about John Key’s long-lasting impact on New Zealand were met with some quizzical stares. Earthquake recovery? Partial privatisation of state assets? Changing the flag? Perhaps this seeming lack of a legacy has something to do with governance by focus group, a symptom of always straddling the political centre. There is not much room for bold policies in the middle.

Some have mentioned Treaty settlements as a possible answer. While there have been a number of agreements reached under the fifth National government, the speed at which they’ve been reached leaves open the question of their durability in the long term. No one, though, can accuse Key’s government of inertia when it comes to Treaty settlements.

Early in Key’s political career it was in no way clear that Treaty settlements might be his most lasting legacy when it was all over. Only 12 short years ago the backbencher MP from Helensville was a member of the pathetic group of “Hollow Men”, led by then National Party leader Don Brash, who tried to take New Zealand’s race relations back a few decades by launching a political campaign focused on alleged Māori privilege.

As Brash and Labour PM Helen Clark tried to outdo each other in their appeals to the Pākehā mainstream, the level of discourse reached a particularly depressing low point. Brash was narrowly defeated by Clark with the help of everyone’s favorite racist grandfather figure, Winston Peters, and we have happily not returned to the same low point in race relations since.

With the help of Christopher Finlayson, a former lawyer for Ngai Tahu during their Treaty settlement negotiations, Key continued blazing the settlement trail that former prime minister Jim Bolger and the first Minister of Treaty Settlement Negotiations Doug Graham had begun back in the 1990s.

He established a partnership with the Māori Party that incoming Prime Minister Bill English looks set to continue. While many of his policies, especially those related to Education and Welfare among other portfolios, have placed further pressure on Māori struggling at or near the bottom of the economic ladder, the revitalisation of iwi and hapu through Treaty settlements will be a legacy that lasts long after Key is gone. The journey was not always smooth sailing, but the immediate results cannot be denied.

While the fourth Labour government put in place many of the key pieces of legislation that created the modern Treaty settlement process including the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1985, the Treaty of Waitangi (State Enterprises) Act 1988 and the Crown Forests Act 1989, it has been National governments that have led the way in the actual negotiation of agreements.

After Bolger and Graham started the ball rolling in the 1990s, the Clark governments of the 2000s did little service to the Labour legacy for Māori in terms of Treaty settlements. In nine years in office a mere 11 agreements were negotiated under the Fifth Labour government, at least four of which had their early negotiations under National. When Finance Minister Michael Cullen took the reins of the Treaty Settlement portfolio in 2008 to salvage Labour’s image after the foreshore and seabed debacle late in the last Clark administration, he was able to push forward the ambitious Central North Island forestry settlement (“Treelords”) and lay the foundation for the ground-breaking Waikato River settlement. But it was largely a case of too little too late.

Under John Key’s leadership and with the significant clout of Treaty Negotiations Minister Finlayson (not to mention countless Office of Treaty Settlements, Crown Law Office, Te Puni Kokiri, Department of Conservation and other officials), nearly 50 Māori groups have finalised a Deed of Settlement. Twelve of those settlements are still awaiting formalisation through accompanying legislation, and at least a handful of those negotiations were begun under the Fifth Labour government, but the number and size of many of the agreements reflect the persistence of the National government to continue the economic revitalisation of iwi and hapu.

The total figure for Treaty settlements reached under National is over $1.6 billion (not adjusted for inflation). This does not include the discounts provided on Crown properties, the financial benefits of the Right of First Refusal and Deferred Selection Process, and the interest paid on settlements between the signing of a Deed and the final passage of legislation. The Fifth National government’s legacy also included the ground breaking Tuhoe and Whanganui River settlements which established a legal personality for Te Urewera and the Whanganui River. The difficulties of finalising the Tuhoe settlement also was not particularly helped by Key’s insensitive remarks about being eaten for lunch by Tuhoe negotiators after the breakdown in those negotiations back in 2010. Nonetheless overall Key has tried to stay out of the way and allowed Finlayson and his officials to do their work.

The speed at which some of these negotiations have gone have been criticised by the Waitangi Tribunal, especially negotiations in Northland with Nga Puhi. The quickly negotiated Ngati Haua settlement was nicknamed the “rocket docket” because of the record time in which it was finalised. Many other hapu around the country have struggled to keep the large groups negotiating with the government accountable to their members, and the pace of urgent inquiries to the Tribunal trying to stop Treaty settlement signings have been steady over the past nine years.

We have gone from inaction under the fifth Labour government to the fifth National government’s doing deals by any means necessary. There must be some middle ground that can be established where long-lasting and durable settlements are signed. Treaty settlements will be a legacy of John Key’s governments in one way or another; only time will tell exactly what kind of legacy that will be.

Dr Martin Fisher is a lecturer at the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, University of Canterbury