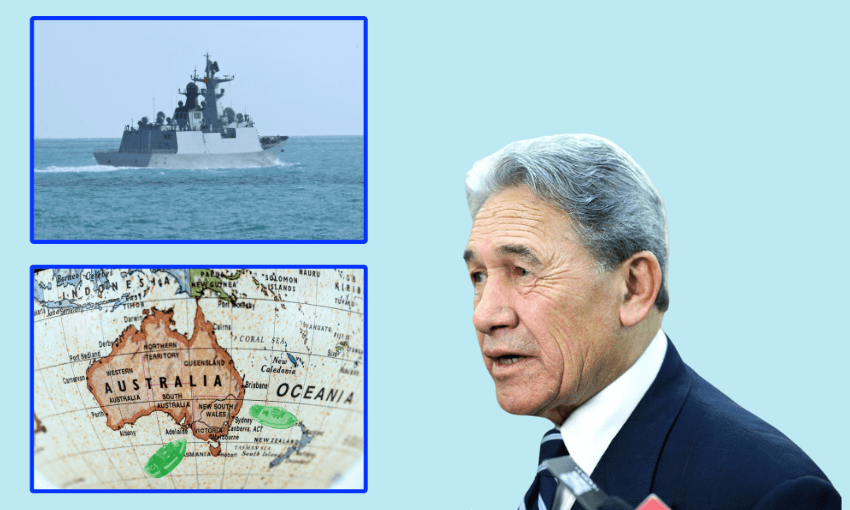

The foreign minister is meeting with his Chinese equivalent in Beijing today, as New Zealand and Australia express concerns over Chinese naval exercises in the Tasman Sea. Here’s what you need to know.

So Winston Peters is in Beijing this week – what’s he doing there?

Like most international trips for senior ministers, today’s talks have been months in the planning. The New Zealand foreign minister is meeting with his Chinese equivalent, Wang Yi, then travelling to Mongolia on Thursday.

What will Peters and Wang Yi discuss?

They’re unlikely to tell the public the line-by-line context of their discussion, but there’s lots to say. “China is one of New Zealand’s most significant and complex relationships, encompassing important trade, people-to-people, and cultural connections,” said Peters in a press release sent last week. “We will discuss the bilateral relationship, as well as Pacific, regional, and global issues of interest to both countries.”

China is a vital economic partner for New Zealand, importing close to $20bn of New Zealand’s goods and services a year, so trade issues will certainly come up. So are some thornier issues likely to, such as New Zealand’s public frustration with a new deal between the Cook Islands and China – which former PM Helen Clark was likely to be a “point of some aggravation” – and questions about Kiribati’s relationship to China after its prime minister cancelled a meeting with Peters. Both China and New Zealand give significant amounts of aid to Kiribati.

And then there are the ships. Last Friday, it emerged that a trio of ships from the People’s Liberation Army Navy had travelled through international waters off the coast of Australia and into the Tasman Sea. Live-fire exercises led to commercial flights between New Zealand and Australia being diverted.

While not breaking any law or treaty – under the UN’s law of the sea, ships can travel where they want, without notice, in non-territorial waters – the move has caused concern in Australia and New Zealand. “Australia and New Zealand ships and aircraft have been monitoring the Chinese fleet while they have been travelling down the coast of Australia … as you would expect us to be doing,” Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese said. The Australian shadow minister for defence, Andrew Hastie, was more aggressive, saying the “provocation” was due to Albanese’s “weakness”. “The Australian people deserve to know what is going on, and they deserve better leadership from our weak prime minister,” said Hastie.

Judith Collins, New Zealand’s minister for defence, called the activity by the navy boats “unusual” and said the government was seeking assurance from the Chinese embassy as to why limited notice was given about the boats conducting military drills. In an interview with RNZ, she linked the ships to the inclusion of seabed mining in the Cook Islands-China deal. “I don’t think New Zealanders should be worried. I think we should be very aware that we live in a world of increasing geopolitical competition, that the seabed of the Pacific Ocean is viewed by some countries as an area of enormous resource,” she said.

What did China say about the ships?

The Chinese government said the responses from New Zealand and Australia had been “unreasonable” and “deliberately hyped it up”. It said the military exercises, including the drills where live weapons were fired, meaning flight paths had to be diverted, were “conducted in a safe, standard, and professional manner at all times, in accordance with relevant international laws and practices”.

In an opinion piece in the Global Times, an English language newspaper that is part of the Chinese state media, commentator Zhang Junshe wrote, “Certain western countries have accelerated their military expansion in the Pacific, using the ‘China threat’ as a pretext to secure defence budgets. This arms race, justified by the ‘China threat’ narrative, stands in stark contrast to the concerns of Pacific Island countries regarding issues like climate change and ocean governance.”

Oh yeah… what’s happening with New Zealand’s defence budget?

While China has been conducting naval exercises, the new Trump administration in the US has been calling for American allies to spend more on defence, with Nato secretary general Mark Rutte saying that partners, including New Zealand, should increase their spending. Currently, New Zealand spends about 1.2% of its GDP on defence, while Australia spends 1.9%. The NZ Defence Force had to cut programmes last year due to a funding shortfall. Christopher Luxon said last week that he wanted to get New Zealand “close” to spending 2% of its budget on defence, and also said he was open to sending peacekeepers to Ukraine. Collins told media the appearance of the Chinese ships delivered a “wake-up call” on the importance of defence spending, promising there would be a boost in May’s budget.

Te Kuaka, a foreign policy think tank that advocates for an “independent, values-driven foreign policy”, said that increased defence budgets should not be the priority. The shutdown of USAID, which provided vital aid to the Pacific, is “the gap that New Zealand should be filling”, said spokesperson Marco de Jong, a historian and AUT lecturer. “Our geography and our relationships in the region are our advantage, rather than seeking to buy marginally useful war fighting capability which doubles as a threat to our largest trading partner,” he told The Spinoff.

How ‘unusual’ is it for Chinese ships to be in the Tasman Sea?

Paul Buchanan, a former US and New Zealand defence analyst and director of geopolitics consultancy 36th Parallel, wrote about the Chinese flotilla on his blog. “If the US, UK, French or other western navies conducted the exact same exercise in the Tasman Sea, there would be little controversy about it,” he said. While “between amicable countries” greater notice for military drills might be the norm, there is no standard protocol or expectation to give extensive notice. (The Chinese gave only a few hours of notice that live fire exercises were taking place.)

“[The Chinese] could have informed New Zealand before the planes left the ground if they wanted to be polite – they clearly wanted to be rude,” Buchanan said.

Buchanan said that China had traditionally been a “territorial navy that stays within a thousand miles of home”. While the ships were not a threat to New Zealand or Australia, they were a demonstration of naval capability far from home shores, and included a supply ship. “Staying at sea for long periods of time, like 60 days, is a capability you have to have as a blue water navy,” he said.

The presence of the ships may be linked to last September’s navigation of New Zealand and Australian navy ships through the Taiwan Strait without asking permission from China, which claims the island nation and its waters as sovereign territory. “The Chinese are showing that if New Zealand and Australia can claim freedom of navigation near Chinese shores, they can do a similar thing – and the Tasman sea is open ocean, not a disputed territory,” said Buchanan.

Will the ships’ presence in the Tasman change anything that New Zealand is doing?

As University of Waikato lecturer Alexander Gillespie explained in this article, the broader context of the Cook Islands deal and the pressure from the US to increase defence spending are not directly related to a Chinese naval exercise. These factors, combined with Peters’ China trip and an approaching Australian election, do, however, lift the stakes.

“In times of international stress and uncertainty, New Zealand has always tended to move towards deepening relationships with traditional allies,” Gillespie wrote. This could be a signal that pushes New Zealand towards closer involvement with the Aukus security deal, something Luxon said last year that he “welcomed”.

“Even if China is a regional threat, it’s not clear whether New Zealand should meet that challenge militarily, or with further alignment with Aukus, especially when the US is currently very unreliable,” said de Jong.

At the very least, Buchanan said, the Chinese flotilla is an opportunity for the New Zealand and Australian militaries to practise their naval capabilities, while the Chinese navy does the same. The New Zealand frigate Te Kaha is shadowing the ships. “It’s an opportunity to find a live target, a flotilla no less, and work on their capabilities, see how their communication works… it’s a wonderful opportunity to test the gear,” he said.

As Peters attends meetings in China, the New Zealand military will continue to observe the Chinese flotilla, another chapter in the story of how China, the US, Australia and New Zealand act in the Pacific. “[The ships] are a cog in a revolving strategic wheel, the big wheel of the Chinese asserting their presence,” said Buchanan. “It’s a flag-waving exercise, to show ‘we can do this’.”