Move over, crewmates – there’s a new captain in the town. Digital Confectioners’ Neil Reynolds tells Sam Brooks how they turned indie game Dread Hunger into a world-beater.

You’ve probably heard of Among Us, the cutesy game that encourages you to mistrust friends and strangers alike. Inspired in part by the party game Mafia and John Carpenter’s film The Thing, the whodunnit-style online game was released in 2018 but blew up during the pandemic. For many, playing Among Us was a way to stay in touch with friends during lockdown, and to get their mind off the grim situation unfurling outside.

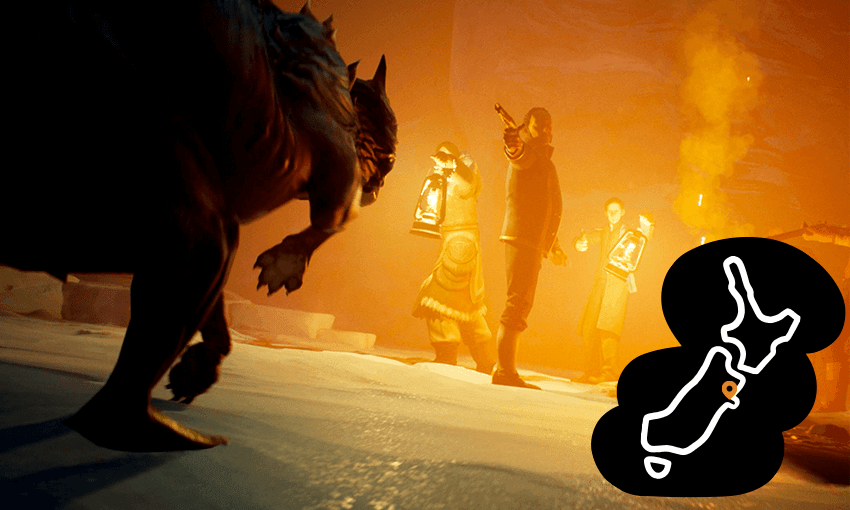

The popularity of Among Us kickstarted a trend for “social deduction” games, and it’s a trend that Dread Hunger is capitalising on, hard. The game, developed by Christchurch studio Digital Confectioners, fits neatly into the social deduction genre but with a twist: it’s set during a naval expedition into the Arctic in the 18th century, with players taking on roles as eight explorers trying to survive in the wintry north. But twist! Two of the eight are traitors who can call on dark demonic powers to ruin the expedition.

The game has been hugely successful, coming in at number two on the Steam global charts behind the juggernaut that is Elden Ring – a game that has been hotly anticipated for three years, with blockbuster names like George RR Martin and Hidetaka Miyazaki it. That competition makes Dread Hunger’s achievements even more impressive. As of writing, Dread Hunger has reached a new active player high almost every day since its initial release in April, and has a current peak of over 76,000 active players.

And it’s come out of a little studio south of the Cook Strait.

Digital Confectioners was founded by James Tan and Sam Evans way back in 2007 as a two person operation largely dedicated to modding – taking an existing game and modifying it with new maps and modes of play. Neil Reynolds, Dread Hunger’s game designer, joined the studio in 2011 as its first employee. Digital Confectioners’ first two games under its own banner were Depth – a shark vs diver battler – and Last Tide – a 100 man battle royale with deep sea divers, the studio seemingly keen to carve out its own nautical niche. From those small beginnings, Digital Confectioners grew and grew. The studio now has 15 employees in total; the team that worked on Dread Hunger is 10 of those.

Reynolds says the game was largely inspired by season one of supernatural horror series The Terror, which followed the aftermath of a terrible 19th century shipwreck in Arctic waters. That show’s mood of creeping fear pervades Dread Hunger – it feels like you’re stuck on one of the earlier Silent Hill ships, albeit with a few more pirate hats, shambling skeletons, and sea shanties. Mistrust and dread, appropriately, lurk in the corners of every frame of the game. The only person you can trust is yourself, whether you’re an explorer or traitor.

“We were already very interested in the social deduction genre,” says Reynolds of the game’s origins. “We played things like Mafia and Werewolf and we saw it as something that could be mainstream, but wasn’t at the time.” Dread Hunger was released this year, but the team started working on it in 2019, a year before Among Us took Twitch by storm. Reynolds estimates that when they started development on Dread Hunger, most gamers had never even heard of “social deduction” as a genre.

“Our plan was to bring it to them.”

The term might have been unfamiliar, but social deduction has long been popular outside of video games – you likely already know the rules of the party games Mafia and Werewolf, for example. Social deduction ignites a part of the brain that most of us try our best to hide – it encourages you to deceive, to trick, and to assume the worst of other people.

But social deduction had never really taken off in video games – until Among Us.

It’s not surprising that Among Us was a hit. The game has an appealingly cutesy design, and the rules are simple enough that they can be understood as easily by young kids who are new to gaming as adults who have spent more time in the gamer chair than they care to admit. Combined with the proven thrill of high-stakes, high-emotion matches, Among Us had a winning formula, especially once half the world went into lockdown in 2020. Now Dread Hunger is riding the undertow of the tsunami that was Among Us – even making headway in China, a market that Among Us didn’t manage to break.

The success of Dread Hunger has come as a welcome surprise to the team who worked on it, says Reynolds. “Almost every single day since launch we’ve hit a new all-time high in terms of players, in terms of sales. It’s been amazing to watch the growth.”

Reynolds attributes part of the game’s success to the setting, one which had already proven popular in the gaming world. It seems that gamers really like to be ship captains (see: Sea of Thieves, Assassin’s Creed: Black Flag, Sid Meier’s Pirates). It’s also a setting that places Dread Hunger apart from other games in the social deduction genre. “Other games in the space are quite cartoony, and they’re not first person. There’s less roleplay for players to do, because they’re not in the character themselves. With us they can really roleplay as an 18th century sailor, or a captain, or a cook.”

The team knew they were really onto something big when the community content began rolling in. “It was when people started making fan art for our game,” says Reynolds. “Then people started making guides and videos on how to play our game. I was so stoked.”

Romy Gellen, Digital Confectioners’ marketing and communication manager, sees the bulk of that community content, the lifeblood of any live service game. “Just last week, I read the first Dread Hunger fanfiction, which was… quite an experience!”, says Gellen. “We’ve even had some cosplays of the characters so far, and people are even cosplaying as they stream.”

So where to from here? The team recently released a “roadmap”, a timeline of things they plan to add to the game like more cosmetic items and prestige classes to play with. But Reynolds anticipates things might change even more. “The constant growth has already meant that we’ve had to make some pretty big changes as we go. It’s been pretty crazy.”

It’s a dream situation for a games studio. Huge launch, new peaks for active players and sales every day, break into an elusive market. What else could they want?

One thing: “I’d love to see more Kiwis play the game. I’d love to be more of a household name here.”