Ride were one of the most powerful and original bands of the British shoegaze scene. Duncan Greive watches them grow, and wishes he hadn’t.

It’s almost impossible to age with any dignity. For a couple of months earlier this year my elbow had a swollen fluid sac bulging out. A friend finds her fingers numb when she sleeps in the wrong position, while another took his first fall “that felt like how an old person would fall”. We’re all in our mid-40s.

Going to see Ride at the Powerstation unavoidably brought us face-to-face with that reality, as the band has grown in ways the audience surely didn’t appreciate.

Ride formed in Oxford in the late 80s, and were quickly signed to Creation, the indie label which would go on to dominate the 90s through bands like Oasis and Primal Scream. Shoegaze – a genre typified by bands like My Bloody Valentine and Slowdive – was a moody, arty music which never really reached mass audiences. It was squeezed by grunge then washed away by the unstoppable rise of Britpop, though lately has had a huge revival driven by its popularity on TikTok, with its textures and hazy, emotive sound matching the current global mood.

In any consideration of the 90s’ most perfectly formed albums, Ride’s debut Nowhere would have to rank near the top. It’s built out of Andy Bell’s guitar, alternately menacing and shimmering, and on top of Loz Colbert’s muscular drumming, with Bell and Marc Gardener taking turns singing in affectingly reedy, post-adolescent keys.

It was Nowhere and its sequel Going Blank Again which drew a decent but not overwhelming crowd – largely male, median age early-50s – to the Powerstation on a wet and windy Sunday night. We were young when those records came out; they meant everything to us. We’re now older and those songs still have that same power, to recall when our stories weren’t written, when our identity was defined by the fact you knew and loved Nowhere more than Nevermind.

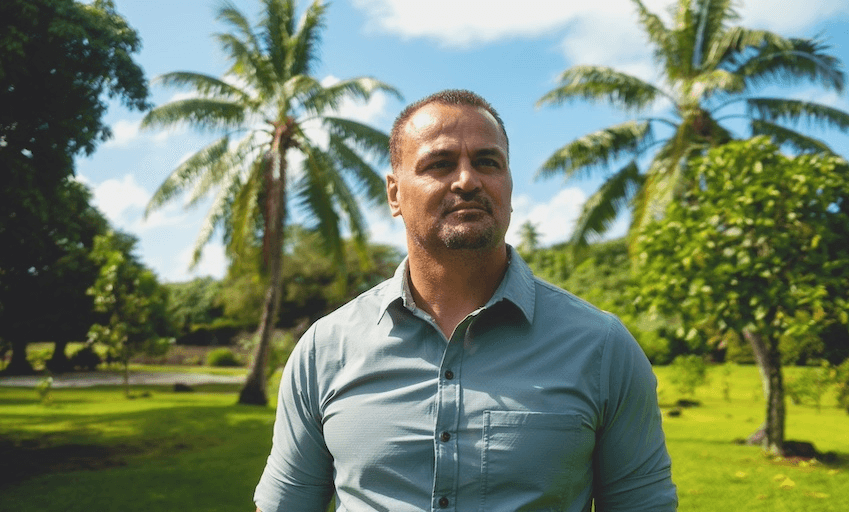

This is what we stood anxiously awaiting, in that beautiful hall. Ride came on stage on the dot of 9pm. Immediately it was apparent that something was different – at least to the mental image we’d built in our heads. Press imagery from the era was all fringes, baggy jeans and enigmatic, withdrawn personalities. Three quarters of the band met that by being solemn and undemonstrative. Andy Bell even had a perfect bowl cut, despite his hair having gone completely silver.

Singer and guitarist Marc Gardener, though, was a problem. For a genre that demands you inspect footwear, his were laceless and pointy in a Chapel Bar-ish way. His neck had a chunky beaded necklace and at least two dog tags, despite not having completed any tours of duty. He wore a blazer. All of this is fine out of context – you have to be cute for you – but was hard not to read as a betrayal of what Ride stood for. It was as if Peep Show’s Jez had taken over the band.

This should be fine, even admirable, because of course he has changed! In the intervening years, we’ve all grown up. Become teachers, lawyers, car salespeople and some unfortunates even journalists. We don’t walk around trapped in our teenage selves. Yet we do expect bands to.

This is the unavoidable tension at the heart of the growing and increasingly lucrative nostalgia circuit: the audience wants the artist to do something that is quite unnatural; something which is on some level antithetical to the modern, pathbreaking origin story of many artists. We want you to transport us back to our youth, by embodying and performing your best impression of your young selves.

Still, there’s growing up, and then there’s growing into the very image of the artist you implicitly stood firmly against. In 1992, Ride’s mystique, their wall of noise and lack of concession to a clean, radio-friendly sound felt both symbolically and sonically powerful. It was jarring to hear the band abandon much of that approach.

The first half of the set was dominated by songs from their recent album Interplay, which Gardener believes to be the best the band has recorded despite evidence to the contrary (to be fair, most artists are trapped in that belief system). The studio versions of these songs are passable. Pitchfork’s review put it well, saying the band “refuse to pander to their classic sound. Their stance is frustratingly laudable – a creative obstinacy to be admired with a slightly heavy heart.” They have dropped the thundering, emotive guitars in favour of boringly competent synth-rock.

Live, they change shape again, and it’s not good. The band they recall most powerfully now is Jesus Jones. The last time Jesus Jones’ name was invoked in this country, it was when The Feelers were commissioned to cover Right Here, Right Now for the 2011 men’s Rugby World Cup – perhaps this century’s most garish act of cultural cringe. Jesus Jones is fine; but they were the exact opposite of what Ride stood for.

It reaches a nadir during Peace Sign, from Interplay. Ride’s lyrics were, in truth, mostly just OK – but that didn’t matter because you felt more than heard them. They have plummeted since. Peace Sign’s chorus goes:

“Give me a peace sign

Throw your hands in the air

Give me a peace sign

Let me know you’re there”

This new sound is weird enough on the new songs, but when Gardener sings Dreams Burn Down like it’s The World I Know, complete with messianic gesturing, it’s breathtakingly weird. It’s as if he’s trying to reframe these beautiful, brittle songs as pre-Oasis pub rock.

Things pick up during a sustained run of early material, especially when Bell – wearing a nice black t-shirt and Adidas Gazelles, perfect – takes more lead vocals. Songs like Kaleidoscope, Taste and the sublime Vapour Trail give us what we came for. But even when the sound is right, Gardener’s generic rock star gestures have a harsh incongruity with the sound and philosophy of the band we came to see.

It forces you into a strange dilemma. Gardener seems happy to be on a stage, and in interviews confident that the music he is making now is closest to the vision they had all along. Yet it feels like a conscious disavowal of what attracted us all there in the first place. The incongruity is hard to shake, even though now, 12 hours later, I remain entirely unsure about which of us has it wrong: him for growing and changing, or us for wishing he wouldn’t.