In the first part of its final season, The Crown strays from the royal family – to its ultimate detriment, writes Sam Brooks.

Mild spoilers for world history circa 1997-98.

What’s all this then?

If you’ve been under a rock or without a Netflix subscription for the past eight years, The Crown is a Netflix limited series that dramatises the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. It’s written by royal enthusiast/critic (depending on the episode) Peter Morgan, who has spent the better part of two decades writing about the royal family.

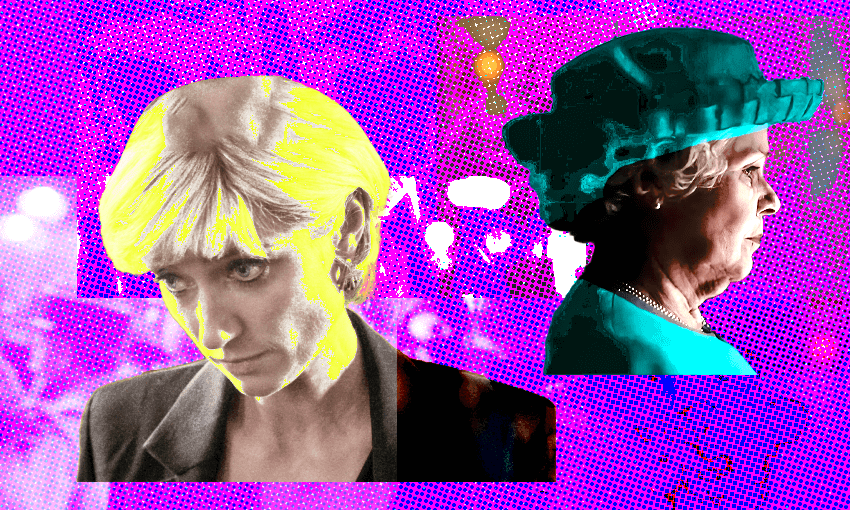

While earlier seasons showed the likes of Claire Foy and Olivia Colman taking up the role of Queen Elizabeth II, with other stars like Gillian Anderson and John Lithgow joining the party as Thatcher and Churchill, the sixth and final season zooms out a bit from its titular monarch (played with appropriate restraint by Imelda Staunton) to instead focus on Princess Diana (played by the consistently tall Elizabeth Debicki).

Or, at least, the first part of the season does. The four episodes released last week focus entirely on the eight weeks leading up to Diana’s death (with a slightly fudged-for-timeline insertion of her walk across a landmine field). The final six episodes, out December 14, are expected to focus on Prince William and the final years of Elizabeth’s reign, wrapping up somewhere in the 2000s.

The somewhat necessary focus on Diana’s death, already covered by Morgan in the 2006 film The Queen, doesn’t work to the series’ benefit, however.

The good

The Crown remains one of the most impeccably produced series on television. As the golden age of the medium slips in and out of view, it remains appointment, event television, and for good reason. It looks (those locations!) and sounds (that score!) like a lot of money has been spent on it. This is the very definition of prestige TV.

The series has always been at its best when it uses the individuals inside the royal family to critique its structure, and its position in not just British, but world history. The best episodes tend to focus on either a single member – see, any episode that followed Princess Margaret – or on an individual outside of the royal family for their frame on the Crown. It’s no surprise that the best episode of the four presented here is one that follows two photographers, a paparazzo and a Crown-appointed photographer, and their very literal frames on these public people.

The performances remain uniformly excellent, too. Staunton has been given a lot less to do during her time as Queen Elizabeth II, but she manages to continue the throughline established by Foy and Colman, of a woman so hemmed in by the structure around her that she might as well be stitched into it.

On the other side – and really, the first three episodes of this four episode run might as well be The Diana Show – Elizabeth Debicki has an even harder job to perform Diana. Not only does she have to make us believe why the world was so obsessed with this woman, she has to do it while portraying some of the hardest times of that woman’s life. It doesn’t help that, as the walls close in on her, Morgan’s lens on Diana does too, and he gives Debicki fewer notes to play, settling on exasperation, anxiety and panic. She plays the notes well, but why hem in a performer as gifted as this one, playing a character as rich as Diana, with so little to do?

The not-so-good

While The Crown might be best when it’s able to critique structures, it is also at its best when it’s able to imagine around what “might” have happened, pitting fictions both likely and unlikely around recorded fact. The problem has been, as it lunges closer and closer to living memory, is that far fewer of those moments exist.

The episode that focuses on the hours leading up to Diana’s death runs a fascinating tension, almost like a thriller (at one point the score swells with sounds akin to literal steel doors slamming behind her), but also one of inevitability. The audience doesn’t just know that this woman is going to die tragically, they probably already have their own emotional connection to it. There’s a reason why people ask each other where they were when Diana died, it’s one of those experiences. Any lens that Morgan has on the situation is going to be a bit skewed.

Perhaps Morgan is struggling against his own past, having explored Diana’s death pretty successfully with The Queen, using the seven days after Diana’s death as a way to interrogate the growing disconnect between the British public and the figureheads that loom over it. That’s the only way that I can explain the strange decision to have spectres of both Diana and her lover Dodi Fayed appear and give advice and solace to the ones they’ve left behind.

I’m not as aggrieved by this as some reviewers, as Morgan has been putting words into the mouths of this family and their associates, dead or alive, for almost 20 years now. On a simple scene-by-scene level, they work, and it’s exciting to see these actors play outside the realms of tortured anxiety and barely restrained grief. However, it’s an odd one and it doesn’t just put ideas into the mouths of characters who are no longer around to refute them, but ideas that don’t even run along the same road that Morgan has paved for them. Debicki might sell that Ghost Diana believes that Elizabeth’s job is to communicate “What it means to be British” to the British public, but Morgan doesn’t make it easy for her.

Morgan has a lot of ideas about the royal family. He appears to have much fewer, or at least less interesting, ideas about Diana, and for a show that has found its most fascinating discourse in the tension between critique and lionisation, it’s unfortunate that he’s been shown up so badly now.

The verdict

The question every watcher of this series has had since it started was how it was going to handle Diana. Well, we got our answer – and it’s a disappointing one. There’s exactly one scene, likely entirely imagined within the confines of a hotel room, where we see her sparkle and shine. It’s like lightning in a bottle, but doesn’t come close to dislodging any memory the audience might have of her.

For much of The Crown, the images and sounds of characters depicted have been able to stand in for history. I don’t know if Elizabeth struggled to cry at Aberdeen, but I’ll never forget the one shot of Olivia Colman forcing herself to tear up. I don’t know if Prince Philip actually went to a men’s support group to deal with his issue, but I’ll be damned if that didn’t humanise him more than anything that he did in real life.

It is perhaps a kindness, then, that The Crown’s version of Diana has no chance of being the defining historical record of the Princess of Wales. She may not have had the last word, but she had the better one.

The Crown (season six, part one) is now streaming on Netflix. Part two is out December 14.