Book publishing, video games and recorded music all faced the enormous power of the internet 20 years ago. Their financial fates have wildly diverged. Duncan Greive contrasts outcomes for three culture giants.

It’s 20 years since Auckland punk band Stereogram’s Walkie Talkie Man had its career arc bent way up after being chosen to soundtrack one of that year’s iPod commercials. It was part of an iconic series, featuring silhouetted figures dancing to the songs, with the iPod the only object in colour. Just one unremarkable data point in the unrelenting march of Apple to becoming the colossus of consumer hardware and software it is today.

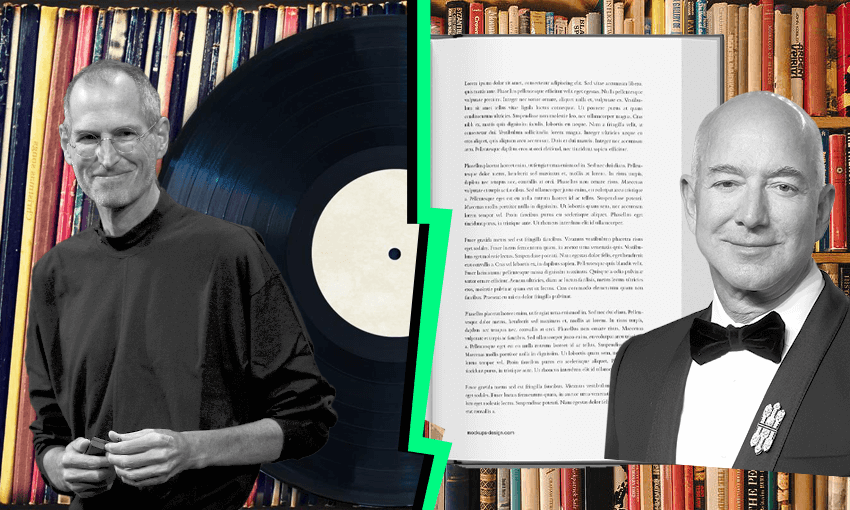

Those ads were hugely significant in pop culture at the time – Apple was the hottest brand in the world, and its beloved CEO Steve Jobs a huge music fan. He profiled like a classic rock boomer – a teenage collector of Dylan bootlegs who dropped acid and dated Joan Baez in his 20s. He was a Beatles fanatic who interviewed Mick Jagger on stage at the launch of iTunes for Windows; all this was core to his identity.

Infamously, Apple gave away a new U2 album to all iPhone owners in 2014, one they did not ask for and many wanted rid of. This was after Tim Cook had taken over, and might mark the moment its interest in music waned, even as its business grew exponentially. Still, during a crucial period – the aftermath of Napster’s decimation of the physical media business – Apple was perceived as a wildly cool company, in no small part because of its relationship with music – largely due to the way iTunes, the iPod and then iPhone made it more accessible than ever.

Down to the river

It’s 30 years since the founding of another tech giant: Amazon. Its founder Jeff Bezos lacked the wild charisma and counter culture cachet of Jobs – he was a computer science grad who ran a hedge fund by the time he was 30. There he met his future wife Mackenzie Scott Tuttle, who had studied under Nobel laureate Toni Morrison and would go on to become an acclaimed author in her own right.

The pair quit to start an online bookstore – though not because of Scott’s relationship to the form. Instead it was because, according to NPR, they were “relatively cheap, they don’t spoil and [are] pretty sturdy to ship”. Amazon was extraordinarily good at selling books online, stocking a vast range, pricing cheap and often shipping free, becoming loved by many readers while viewed with deep suspicion by many publishers and authors.

Amazon moved from there to CDs and video games and toys before becoming the “everything store” we know and have complicated feelings about today. That is a brief version of the origin story of this enormous global business which runs from cloud computing to advertising to logistics to streaming TV and movies. All built on the book.

Yet for all that, the book world never felt about Amazon the way the music industry did about Apple. The company got into wars with publishers and authors, bankrupted both chain stores and indies alike. Its general theory of satisfying customers by crushing margins to increase volumes was viewed with suspicion by most of those who made, loved and sold books.

Can it all be so simple?

To this day Amazon’s reputation as a heartless company which cares nothing for culture persists, while Apple is popularly perceived as a relatively benign overlord – the maker of dazzling devices, and one which transfers the issues with creaky culture industries to the apps which run on its beautifully engineered machines. On that basis, you’d think publishing should rue the day Amazon chose books, and be envious of Steve Jobs’ fascination with song.

I’m here to humbly suggest that belief is dead wrong. To illustrate why, consider three charts, starting with gaming revenue.

Revenue for books (even this is incomplete, as like-for-like figures aren’t public):

And for recorded music.

What you see here is three commodities. All remain hugely impactful in culture. But two have broadly retained or significantly expanded their economic foundations, while the third remains a shadow of its former financial scale. I’ll attempt to explain why, as I think it all ladders back in part to those two tech titans.

Video games have become the dominant entertainment medium. This has been driven by competition both between games and between platforms, along with the explosive growth of mobile gaming. Gaming has steadily risen from an esoteric hobby associated with teenage boys into a mainstream activity with its own media (Twitch), sales platforms (Steam), user generated content worlds (Roblox) economic models (in-app purchases, in-game currencies), adding up to a cut-through in which roughly two thirds of US adults say they play video games.

Books have remained largely physical media, with e-books mirroring and complementing the printed form. The rise of streaming TV and movies has led to expanded markets for rights for both fiction (Game of Thrones) and non-fiction (Killers of the Flower Moon). Where social media has impacted books, it is most prominently associated with the #booktok phenomenon, a new promotional channel opening both classic and modern books up to a new generation.

Music remains perhaps the most kinetic cultural force in the world. Taylor Swift has more fame and generates more revenue than any other individual in pop culture. Live music has exploded particularly post-pandemic, with theatre artists packing arenas and arena artists selling out stadiums. Previously regional genres like reggaeton, country and afrobeats have vast global fanbases. Music was the driving force which underpinned TikTok, and remains a massive part of YouTube usage.

Digital love?

A case can reasonably be made that all have culturally thrived in the digital age. Yet their economic fortunes are reflective of a very different reality to practitioners. To be clear, it has never been a great time, being an author, musician or independent game developer. It has always been a winner-takes-most economy, and likely always will be (and arguably, should be). But the gulf between cultural impact and financial reward exists, and it’s largely down to how the public accesses the work.

For books and video games, it’s mostly through sales (or, in mobile gaming, in-app purchases). The book world is alone in culture in that the most common engagement with the form is still through physical media – hardbacks and paperbacks, whether bought online or in a store. By contrast, video games are downloaded, DVDs are mostly streamed, and, despite a recent revival, vinyl and CDs are a tiny proportion of consumption compared to streaming music.

Video games remain tightly connected to the hardware they run on. Premium titles for the latest generation of PlayStation, Switch or Xbox have established $100+ as a price point and can sell tens of millions of copies. Mobile games operate within Apple and Google’s app stores, either purchased outright or funded through a massive array of microtransactions for everything from extra lives to special digital outfits.

Music, by contrast, is nearly entirely a subscription phenomenon for consumers. Pay a single price and get access to almost everything ever recorded. It has become a form of user-generated content, with millions of artists and songs uploaded, most getting a risible number of listeners. It has a huge presence on YouTube and TikTok, yet the majority of the upside is captured by the platforms, which sell advertising around music, rather than artists or labels.

Spotify, the subscription company which had a major role in the current paradigm, is locked into a toxic relationship with the music industry, with entangled shareholdings and revenue. Toxic because despite its close ties, many artists feel Spotify grossly under compensates them for their work. Spotify, for its part, has to give up around 70% of its revenues to music rights holders, and therefore spends a lot of its time trying to get its audience to listen to anything but music – hence the bet on podcasting, and now audiobooks.

Still, it’s telling that there is a hard cap of 15 hours on the amount of audiobook listening which can happen within a Spotify subscription (and that audiobooks are a relatively niche part of the publishing revenue pie). Book publishing has resisted becoming a subscription all-you-can-eat product, and rightly so. Video games are much the same. Despite Sony and Microsoft launching subscription products, video game publishers are much more committed to sales than bolstering subscription models.

The sound of the crowd

They’re right to do so. Music offers a cautionary tale – with artists battling for attention in a wildly crowded market, and forced to use platforms that either want you to listen to less music (Spotify) or for which music is just a small part of their much larger businesses (Apple, Amazon, YouTube). It’s driving artists to some behaviours they can’t possibly want – big artists releasing endless colour vinyl variations to hose their most ardent fans; smaller artists setting up subscription services to sell access to their demos.

All because all music fans, from the most obsessive to the most casual, pay the same amount in the digital realm. Whereas with books and video games, the more you love the form, the more you pay.

The origin stories of this situation are complex. Books are just a really nice physical product, and the experience of reading one on a glass screen is manifestly worse. Gaming benefits from specialised hardware, and it so moreish that fans will happily pay up to keep a streak going.

Music fans, meanwhile, were often buying a whole album just to listen to one or two songs. Radio had proven that, for many, listening to a variety of artists together was a more preferable activity than consuming a whole album.

Still, this was not an active choice, made by music rights holders as a collective with a considered assessment of their interests. Between Napster and iTunes and then YouTube and a nascent Spotify, there was existential dread about the financial basis for music. They took the deal because they felt like they had little choice. By contrast, books and video games had arbitrary but meaningful differences in choices, and took different paths.

To be clear, revenue is not the whole story. Creative vitality is more than just finance and distribution, and the opaque way money is carved up by the giants of video games, book publishing and music labels brings complexities of its own. Indisputably, though, the more that flows to the rights holders, the better.

It’s also important to note that these worlds are now much more complex than the formats alone, and being sold over rented is hardly a guarantee of a better deal. They’re often dictated by the cut the platform takes. This varies wildly in the unregulated libertarian idyll of the internet. Substack takes 10%; Google Play, Apple and Steam, mostly 30%; Amazon for ebooks, 35%; YouTube takes 45%-55%; Roblox around 75%, which still beats the miserable shares from Meta and TikTok.

Still, the gold standard, highest cultural impact format for music, books and video games remains the album, the book and a console game. Now, two or three decades on from some crucial inflexion points, we live in the shadow of those junctions. Down one path lay individual sales, down the second, all-access subscriptions. Despite subscriptions being a great consumer product and a brilliant technology business, they seem to work much less well for creators.

Looking back, it’s interesting the extent to which the philosophy and interest of two companies were crucial in all this. Amazon built its business on selling you things, and wanted to do the same in digital – so it created the Kindle, a superb piece of consumer technology that also wants to sell you individual units of digital culture. Apple just wanted to sell hardware, and take a piece of every transaction – hence first iTunes, then the app store.

The creation of music, books and gaming is not all that different. A certain amount of vision, individual and collective effort, to create products which bring joy to millions. But the financial underpinning and incentive structure of these three disciplines is wildly divergent. And the role of two companies, with very different relationships to culture, helps explain why.