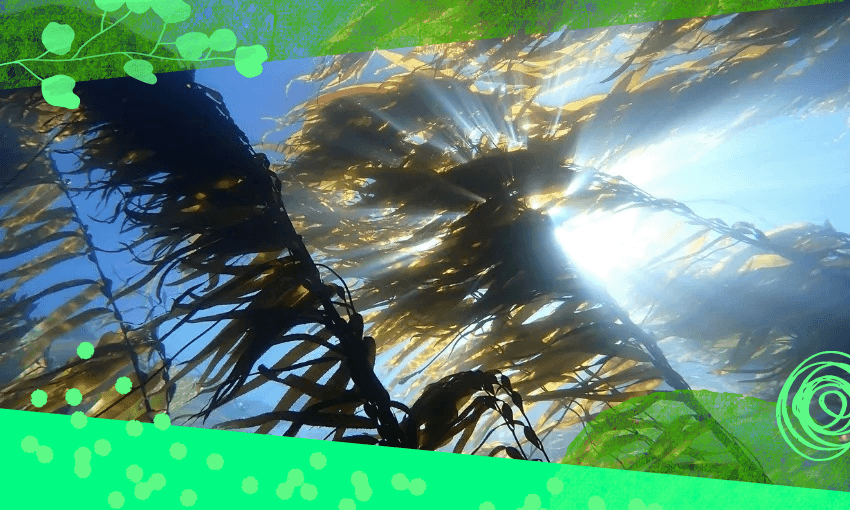

Beneath the waves, kelp forests are disappearing. Can we bring these climate superheroes back?

This is an excerpt from our weekly environmental newsletter Future Proof, brought to you by AMP. Sign up here.

“When you start to look really closely, it’s really beautiful. When you start to notice it all,” says Zoe Studd, executive director of Mountains to Sea Wellington. “They’re just as important as our forests on land. It’s just that we don’t get to interact with them as much.”

Studd is waxing lyrical about seaweed. Perhaps seaweed makes you think of sushi. Or maybe something unwelcome touching your foot in the surf at the beach. “How do we get people to care about this seaweed thing that people often find quite creepy?” she wonders. “We’ve got a PR campaign to run here.”

That PR campaign takes the form of Love Rimurimu, a Wellington-based project covering “every aspect of seaweed nerdery”. It connects communities with our lush, underwater kelp forests through activities like guided snorkel days, and is also helping to figure out how we might be able to restore this ecosystem.

Around New Zealand – and indeed globally – kelp forests are disappearing. Sedimentation darkens coastal waters, smothering seaweed. Kelp is munched into oblivion by an overabundance of grazers like kina, whose population explodes when we humans fish out too many big snapper and crayfish that usually keep their numbers in check. And of course climate change is heating up the oceans too.

In 2021, the folks at Love Rimurimu asked the rangatahi at Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Ngā Mokopuna on the Miramar Peninsula Motu Kairangi: if you were going to do restoration, where might you do it? After examining temperature, sedimentation, and even old place names, the “Kura Kelpers” presented a restoration plan to mana whenua Taranaki Whānui, and the project scored a five-year resource consent to replant and experiment.

This past September, the first giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera) babies returned to the waters of Worser Bay. Rocks inoculated with seaweed spores were grown in an aquaculture facility at NIWA, Studd explains. First, the rocks develop a brown fuzz. Then the baby kelp grow a holdfast – the structure that clings to the rock – as well as a stem (called a stipe) and a single blade. “They’re super cute,” says Studd. “We try and get them to about five centimetres before we plant them out.”

After karakia and waiata, rangatahi freedivers swam out to place the seaweed-laden “green gravel” into restoration plots, which continue to be intensively monitored. “Rachel, who runs our community science monitoring staff, she knows all the rocks. She knows all the seaweed intimately,” says Studd. The restored kelp plants now number 300, and some have already grown to over 60cm long. But the process has come with challenges.

“We’ve had an octopus come through and push over our rocks. We’ve watched a fish eat our seaweed,” says Studd. The team aren’t managing grazers like kina, but are open to learning and adapting their approach if it means successfully bringing back kelp.

There’s good reason to restore these lost forests. Kelp absorbs carbon – up to 52 tonnes per hectare per year, more than double that of pine trees, according to NIWA. It also improves water quality, reduces localised ocean acidification impacts, and buffers coastlines from destructive wave energy. Then there are the biodiversity benefits: “It’s a three-dimensional ecosystem that has habitat, shelter, a place for reproduction. And it’s a food source as well,” says Studd. “Everything relies on seaweed being there and being healthy.” Including us.

“That feeling you get when you’re floating over a seaweed forest for the first time, particularly in a marine reserve where it’s so lush, is transformative.”

Mountains to Sea Wellington is running free community snorkel days in Taputeranga Marine Reserve if you too would like to experience the magic of kelp forests.