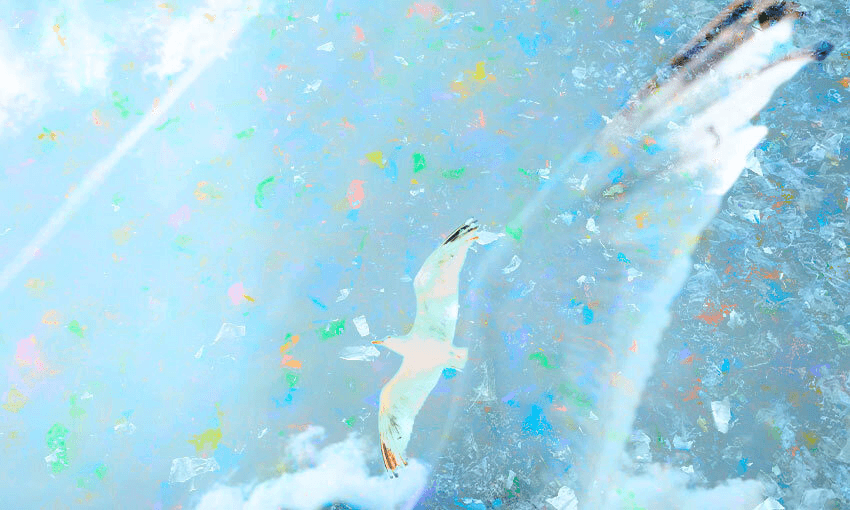

Microplastics aren’t just swirling around our oceans, they’re also floating around in the air and that could be influencing how our climate is changing. Mirjam Guesgen reports.

Tiny chunks of plastic smaller than the width of a sunflower seed are in our skies and they may be helping cool the climate, according to New Zealand research published today in the journal Nature.

But the study’s authors warn that we shouldn’t see this as a good thing, given that the cooling effect is very minor and because of how little is known about these plastics.

Just like microplastics in the ocean, those in the air come from plastics breaking down either in the environment or in our homes then being let loose in the air. They might include fibres from synthetic clothing or textiles, bits of paint flakes, tires or sewage sludge, explains University of Canterbury environmental physicist Laura Revell, who co-authored the study. Microplastics in the ocean can also become airborne as they’re swept up in seaspray, she explains.

Once they’re in the atmosphere, microplastics can reflect sunlight back out into space and cool the atmosphere – a phenomenon known as negative radiative forcing.

In this latest study, researchers from the University of Canterbury, the MacDiarmid Institute and Victoria University of Wellington used a global climate model to calculate how big the radiative forcing of two types of colourless microplastics, fragments (chunks) and fibres (threads), would be. They also factored in where in the atmosphere the plastics were floating around, down low near the ground or up high.

The study estimated that, overall, microplastics cool the atmosphere somewhat by reflecting sunlight. That effect was greater if the plastics were in the bottom 2km of the atmosphere. It’s a small effect though, says Revell, near “insignificant”.

But how much of an effect those plastics have and will have on the climate is still unclear. “It’s quite uncertain due to a whole number of data gaps in our analysis and the assumptions we had to make,” explains Revell.

“I’d be very careful about saying it’s good for the climate because we could just as easily be wrong and it could be an overall warming effect.”

Some of those unknowns have to do with how airborne microplastics are spread out across the world. The model assumes it’s uniform, with one bit of plastic per cubic metre, but that likely overestimates how much is over the oceans and severely underestimates how much is over cities.

Beijing, for example, is recorded as having concentrations of more than 5,500 bits of plastic per cubic metre. A recent preliminary study by Revell’s team found microplastic in the Christchurch area too, although at much lower levels.

Plus, scientists estimate that around half the plastic in the air is smaller than 5mm (the definition of a microplastic), with some in the nano-, or less than one micrometre, size range. That means there may be way more plastic in the air that this latest study didn’t account for.

And very little is known about how microplastics interact with the other stuff in the atmosphere. One of the big wins for the most recent IPCC climate report was that scientists are now figuring out how different facets of the atmosphere, like clouds or winds, interact. But they’re not there yet with airborne plastics.

“There’s so much that we don’t know in terms of what else microplastics are doing in the atmosphere. We have no idea, for example, if they’re involved in other atmospheric chemistry,” says Revell. Other particles in the atmosphere can help form clouds for example, which amplify the effects of greenhouse gases.

What’s more clear though is how horrible airborne microplastics can be for human health. They can lead to breathlessness, crackly breathing, developing cancer or might just literally cut you up from the inside out.

And it’s likely that the amount of microplastics will increase in the coming years. The amount of plastic in landfills and the environment is set to double by 2050. As it, as well as what’s already there, breaks down it gets cycled between land, air and ocean.

“We really think about the plastic cycle now. Microplastics cycle through all parts of the Earth’s system,” says Revell.

That means while there may be little to no effect on the climate and us now, there could be bigger issues in the future.