What’s worked, what’s gone wrong and what’s now brewing in Aotearoa.

Sorry, I’ve been deep in a doom scroll. Remind me what we’re talking about?

Australia’s world-first “ban” on under-16 year olds having social media accounts kicked off last Wednesday, with the Sydney Harbour Bridge patriotically illuminated in celebration.

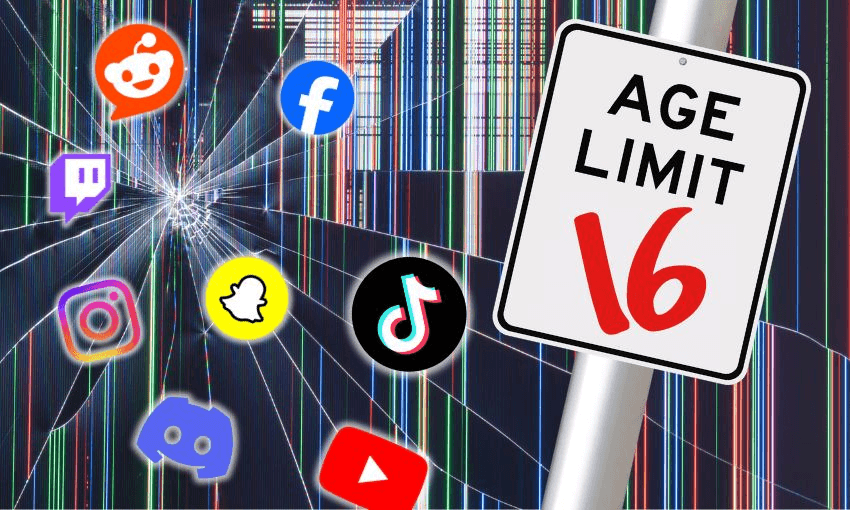

The new legislation affects pretty much every teenager in Australia; 95% of 13 to 15 year olds use social media, according to a February 2025 report by the government’s e-safety commissioner. It also showed 80% of 8 to 12 year olds had used one or more social media platforms in 2024 and 36% had their own social media accounts. However, under the new laws, none are legally allowed to start or retain accounts on YouTube, TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, Facebook, Threads, Twitch, X, Kick or Reddit.

Platforms designated as “age-restricted social media” must now take “reasonable steps” to prevent under-16-year-olds from having accounts, otherwise they could face court-ordered civil penalties and be fined up to AU$49.5m.

Oh boy, that can’t have gone down well.

Though some kids support the restrictions, most teenagers aren’t particularly stoked. The Complaints are wide and varied, and include that the law has curtailed their social lives and community, restricted freedom of speech and access to information. Two 15 year olds, Noah Jones and Macy Neyland, are taking their grievances all the way to Australia’s High Court. Supported by The Digital Freedom Project, they’re challenging the federal government, arguing that restrictions impinge upon the “implied freedom of communication on governmental and political matters”. Their case will be heard early next year.

Some parents aren’t jazzed either, saying they’re concerned about social isolation or worried the ban could drive young people into darker corners of the internet. Others are actively helping their children circumvent restrictions.

The Greens have called Australia’s policy “rushed and reckless” and instead suggested reducing the “damage being done by poisonous algorithms”.

Similarly, the Australian Human Rights Commission expressed “serious reservations” ahead of the legislation coming into effect, warning it could undermine human rights as outlined in several international treaties.

Amnesty International described the move as an “ineffective quick fix” that is “out of step” with generational realities. It called for “robust safeguards” to minimise harm caused by platforms’ “relentless pursuit of user engagement and exploitation of people’s personal data”.

Other than pissed off teens, what else has gone badly?

Social platforms have to enforce age limits themselves, choosing their own methods to do so. The result? On day one, many Australian teenagers retained access to their accounts, while others were kicked off immediately.

That wasn’t the only day one drama. Ever the innovators, teenagers worked out how to trick the systems. Many used VPNs to change their location, used makeup to appear older, or enlisted family members and used their faces or ID. Some simply changed their birthdate and supplied a selfie that met the age estimates of a platform’s identification service. Australian parents told ABC some children as young as 10 were age-verified as 30 years old.

Though it’s been framed by global media as a “social media ban”, that’s not completely accurate. The Australian government has stated as much: “It’s not a ban, it’s a delay to having accounts.” Age restrictions apply to accounts, not access, so it doesn’t actually stop a teenager from using platforms like YouTube or Reddit while logged out.

The act might yet be expanded. Teenagers turned to alternative social platforms like Lemon8 (owned by TikTok’s parent company ByteDance) and Yope, but both have since been “put on notice” and it’s expected they’ll be roped into the ban.

Questions have been raised about platforms excluded from the age-restriction conditions, including messaging apps like WhatsAapp and Messenger, as well as Discord, Pinterest and Roblox, the latter of which has voluntarily introduced age-verification in Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands.

Alright, well what’s been successful then?

Australia’s legislation places the responsibility and any punishment on social media platforms, rather than users or families. “There will be no penalties for under-16s who access an age-restricted social media platform, or for their parents or carers,” according to federal guidelines.

The not-a-ban ban appears to be working as planned. Meta has begun deactivating accounts on Instagram, Facebook and Threads. TikTok had, according to communications minister Annika Wells, already deactivated 200,000 accounts in the first couple of days. Snapchat is using an age verification system, k-ID. This requires users to supply government-issued ID, or supply a selfie, which is then assigned an estimated age range.

How have the platforms responded?

YouTube reportedly paid The Wiggles to encourage Wells to reconsider the platform’s inclusion. Meta confirmed in a published statement that while it was “taking the necessary steps to comply with the law” the company did not believe the legislation was the right course of action. Snap “strongly disagrees” with the classification of Snapchat within the restrictions, but will comply. Reddit called the law “controversial” and said it disagreed with the scope, effectiveness and privacy implications of the move. Platforms have also suggested that the burden of age verification should fall on app stores run by Google and Apple instead.

Does this set a precedent?

Pretty much. At the very least, we all seem to agree that these platforms can cause harm. Australia has shown that countries can, if they want to, regulate global tech platforms. However it also shows that doing so is complicated.

So, will New Zealand follow?

It’s too soon to say, however, there’s momentum building in New Zealand. In October National MP Catherine Wedd’s members bill was drawn from the ballot; it mirrors the Australian model and would require social media platforms to prevent under-16s from having accounts. Christopher Luxon is “deeply supportive” of setting the age limit for social media at 16 and wants to “protect our kids from the harms of social media”.

Education minister Erica Stanford told 1News the government is looking “very closely at what Australia are doing” around the issue and how to “make social media companies change their behaviours.” During an appearance on Duncan Garner’s podcast she said she wanted under-16 year olds banned from social media before the next election.

Advocacy group B416 also wants an age limit. Texts from co-founder Anna Mowbray to Luxon show the group’s mission was aligned with the legislation, though she was disappointed the bill’s announcement wasn’t timed to work better with B416’s campaign launch.

Labour has also drafted a social media safety bill (still in the biscuit tin) led by broadcasting and media spokesman Reuben Davidson. It would see “designated” providers held responsible for restricting “harmful” content, with $50,000 fines for non-compliance.

The Act party disagrees with an outright ban. MP Dr Parmjeet Parmar initiated an inquiry into harm experienced by young New Zealanders online. The research has been released in an interim report, presented by MP Carl Bates, and lists social isolation, attention issues and anxiety as issues. It also notes that as well as content, platforms themselves can cause harm. “Design choices of digital media platforms – such as the user interface, algorithms, levels of customisation, and user controls and settings – are not neutral.” While Act called for the inquiry, it responded to the interim report by requesting patience rather than “knee-jerk” reactions. The final report, including recommendations and potential solutions, will be released in early 2026.

Across the aisle, the Green Party has also questioned the efficacy of age-related bans, with co-leader Marama Davidson telling Herald Now that it risked “punishing young people for the harm that Big Tech giants are causing” and platforms need to be held to account.

What other countries are trying to leash the beast?

Quite a few. Denmark plans to copy the Aussies in banning social media for under-15 year olds (although parents could have rules requiring teenagers to have parental consent to use social media.

In November, the European Parliament voted in favour of a non-binding, non-legislative report calling for increased online regulation. 483 MEPs were in favour of an EU-wide minimum age of 16 for “access to social media, video-sharing platforms and AI companions” with parental consent (under-13 year olds would be totally banned). The parliament has also called for addictive features, like infinite scrolling and auto-playing videos, to be curtailed, engagement-based recommender algorithms to be banned and a “curfew” to be imposed.

Malaysia is implementing a ban, which kicks in on 1 January 2026. In India, where TikTok has been banned since 2020, the government is looking into parental consent and age verification too.

Nepal’s government tried. In September it blocked 26 different platforms (including WhatsApp, Facebook, YouTube and LinkedIn) amidst anti-corruption dissent. The ban incited youth-led protests that overthrew the government, led to fatalities and saw the prime minister resign. The country’s new leader was swiftly elected – via Discord.