Hundreds of performers, dozens of volunteers, and (hopefully) a whole lot of sunshine make up the Farmers Santa Parade, but they’d be nothing without Pete Taylor.

In 1934, when the first Farmers Santa Parade – or “Santa’s Grand Parade”, as it was known then – made its way along Queen Street, the floats were drawn by horses and tractors, and the characters waving from them included Waggles and Goggles and The Big Fiddle. Today the floats are a bit more high-tech, but they remain the highlight of the annual parade. Where else but Auckland’s main street a few weeks before Christmas can you see a flying horse, a giant tyrannosaurus, or a sleigh pulled by reindeer, dolphins and a kiwi?

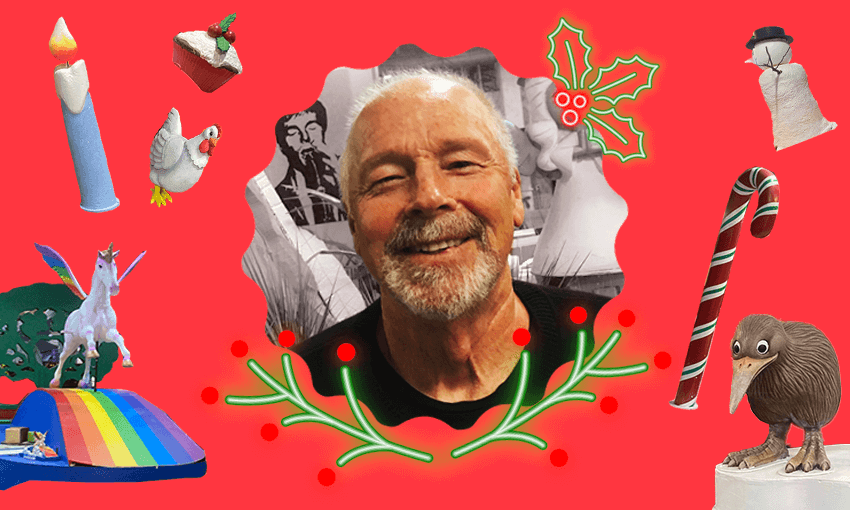

While many of these floats are now familiar to Aucklanders, most of them aren’t aware that almost all of them are created by one man, in a workshop located barely a kilometre from the parade route. His name is Pete Taylor, and he’s been the man behind the Santa Parade for 50 years.

Just under the bright yellow Golf Warehouse sign in Newton Gully is the closest thing you’ll find to Santa’s Workshop in the CBD, albeit one that probably smells a bit more like paint and melted plastic than the one in the Arctic. At Pete Taylor’s workshop, a massive dragon sits next to a flying Pegasus, just a few metres away from six fibreglass reindeer and an angel waiting to be put on top of a Christmas tree.

“It’s one day of glory, and nobody knows what the hell goes into it,” says Taylor of parade day – this year’s is on Sunday, November 27 – as he shows me around his collection of spectacular floats that are paraded through the CBD for just a few hours each year.

Taylor’s history with the Santa Parade stretches back to 1972, when he was employed in Farmers’ display department and was offered the opportunity to work on the parade. At the time it was a small operation consisting of a designer/artist, a builder, and Taylor and one other assistant.

“I didn’t know a hell of a lot to start with, to be perfectly honest,” Taylor recalls. “My dad had taught me a lot about building, I was half good at drawing, but I wasn’t really experienced.”

What goes into a Santa Parade float has changed massively in the half century that Taylor has been making them. Back in the 70s he’d start by making a wooden frame on which he would staple wire netting, and then cover it with papier mache. “I used to use a lot of crepe paper,” he says. “If I was doing a fairy queen float, and I wanted to make pink clouds or whatever, I’d put my wire netting, my wooden frame, and then get these crepe paper flowers and twist them all around.”

The floats, he says, were “very labour intensive and very vulnerable to the weather”. Now they’re made from a mixture of fibreglass, chip board and polystyrene. They’re designed not just to withstand the weather but withstand time – “forever and a day”, as Taylor puts it.

In the old days, a lot of the floats were self-propelled – they had a car driving underneath them, built into the float – but as time went by, they would end up having mechanical problems. Nowadays, they’re all pulled by cars, often supplied by local Toyota dealerships.

Each float can vary from six metres long to well over 10 for one of the headliner floats, and can weigh up to three tonnes. Those headliner floats, like the one that Santa and the grand marshal are on, can take anywhere from three to five months to complete, and are designed to be used for several parades before being retired.

Despite the months of work that go into each creation, Taylor wishes he could do more. “I always used to feel disappointed because you had to stop at a certain stage of the float. I could go on and on, but there’s just not the time.”

There’s a parade to get ready for.

In the early days Taylor and his small team would drive the floats from the workshop to the parade route themselves. “Quite often, there’d be rain and some of the papier mache would fall off the floats, so we had a day to repair them. Most of the time, we were very very lucky!”

These days he has a team of around 10 – including his ex-Air Force brother-in-law, a mechanic, and a civil engineer – to help move the floats on parade day. The big challenge is actually getting the massive floats out of Taylor’s workshop, a very careful game of reverse Tetris.

While they usually start the move-out at 5am, “if the weather’s wet, we might hold off because we don’t know whether it’s going to turn, really howl, or not. You don’t want to get them all outside, go to all that… and then go, oh no, we’ve got to take them back in.”

They try to get them to their starting location in the CBD by about 10am. That gives them another three hours before the parade starts at 1pm, but it’s time they need. “It’s just a logistical nightmare,” says Taylor. “Once you get all the floats down there, you never know what damage they’ll have … and you’ve got to fit the damage up.” For more delicate floats, he’ll take the more easily damaged parts off during the move, and re-attach them before the parade. (Pegasus, for instance, gets briefly dewinged.)

After touch-ups and repairs, the floats are good to go and Taylor can watch the parade, an event that has always been a family affair. Back in the early days he sometimes performed as King Neptune, and all three of his kids have participated in the past. This year, he’s looking forward to seeing two of his three grandchildren waving from a float – a perk of being related to the man who made it.

When the parade is over there’s a kilometre-long trail of floats to get back into the workshop – another game of Tetris. By the time they’re all put away, it’s about six in the evening. The floats are ready to be dismantled, recycled, or kept maintained for next year’s parade.

Taylor will be working on that one too, and he doesn’t see himself going anywhere anytime soon. “There are times when I go, shit, I can’t wait to finish that in the morning,” he says, looking proudly at the very float that his grandkids be on later this weekend.

“I don’t know whether an accountant gets that feeling looking at a spreadsheet.”