I always hated my large, droopy, weirdly uneven boobs. Could surgery finally ease the hurt and shame I’ve been carrying for decades?

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

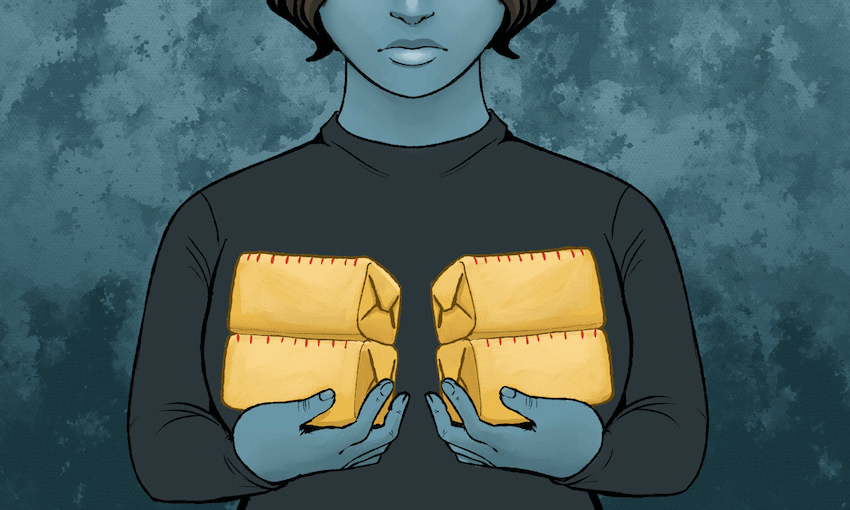

Original illustrations by Jem Yoshioka.

The only two female plastic surgeons I could find in Wellington are booked until 2023, so I’ve settled on a male surgeon. The private hospital is in the suburbs and I wait in the reception area for a few minutes before being whisked through to the consultation room by a smiling assistant.

Dr Paul (not his real name) is genial and soft-spoken with a firm handshake and an agreeable bedside manner. Instead of a practised medical spiel, he asks me to recount how I’ve ended up in his office wanting to know about breast reduction surgery. I have participated in a lot of therapy sessions in my time and this feels close enough to one that I can relax and give him my origin story.

Breasts didn’t really factor into my life until I went through puberty. I’m sure there were giggled conversations about boobs with my friends if we saw them on TV, but I was used to them, growing up in a house full of females. My mother was very relaxed about her nakedness when we were kids so breasts were just a continuation of heads, shoulders, knees and toes.

Then came high school. While co-ed schools have endless benefits, going through puberty alongside a bunch of 14-year-old boys makes one feel acutely visible – like being under a sweaty microscope forged out of testosterone and tasteless jokes about wanking, pubes and tits.

I also had the added complication of a six-month transformation from a teenager whose body was basically straight up and down to a teenager with boobs that could fill an E cup.

What to do with these two new pieces of body furniture? Putting them in a bra was only the start of my troubles.

There were the changing rooms before and after PE class to navigate: did I look the same as the other girls? Did any of them notice that I wasn’t naked?

And what to wear now that I had something(s) to hide? I went for large t-shirts or basically anything that turned them into shapeless objects under cloth, rather than lumpy double scoops of ice cream under a Glassons bodysuit which a lot of my girlfriends wore.

I had a paralysing fear that a member of the opposite sex was going to spot them and put a notice in the school paper, outing me and my floppy boobs. A rumour went around the school that a boy in fifth form had a pair of x-ray vision glasses that could see through clothes. The terror kept me home for nearly a week.

You see, I didn’t love my new acquisitions. They had grown faster than any action plan my mother and I might have put in place to carry their weight, and once they had reached their full size they were just …. not what I was expecting.

By this stage, I’d done some research into what breasts should look like: Baywatch and Beverly Hills 90210 were ideal case studies for globes that bounced in bikini cups no bigger than a Dorito. I had also peeked at my mates’ chests at sleepovers and their bodies by and large seemed to be adhering to this new regime of boobs that were fully containable in A or B cup bras.

But mine? I had angry red stretch marks covering most of each breast that gradually faded to distinctive purplish lines with a sateen finish. Oh, and, the nipples were in the wrong place. There is no other way of putting it, they weren’t two little buds sitting up top, they were shameful nubbins that drooped towards my belly button, like pebbles sliding off a balloon.

By the time I was 18, the murky podginess of my teenage years melted away, leaving in its place a slimmer figure that I greedily ran my hands over as often as I could. My breasts had also shrunk down to a B cup (hurrah) but this hadn’t fixed the drooping issue. It made me hideously self-conscious. Whenever I undressed in front of a new sexual partner it felt like false advertising; my breasts did not resemble the ones found on young women in fashion mags or even on my friends.

It was the 1990s, and society had a slavish addiction to late-stage capitalism and body surveillance, so alongside the tokenistic shrieks of “girl power” from the Spice Girls, media was awash with images of supermodels who wouldn’t get out of bed for less than $10,000, and nothing but perfect breasts as far as the eye could see. At least this was how I perceived it.

I also couldn’t see at the time (and not for many, many years) that the greatest gift I could have given to myself was pride in and acceptance of my body, which was box-fresh and pretty fabulous really.

Dr Paul carefully makes notes as I talk. Every now and then he tilts his head slightly giving a faint yet encouraging smile, exactly what you want out of a health professional who is about to closely examine the part of your body that you hide in a bra shaped like a battleship.

“Right,” he says, standing up and smoothing his chinos out. “Why don’t you come and stand in front of this mirror here and take your top layers off, and your bra.”

He has a little section of his room set up as a photography studio.

“Do I get to come back once this is done and do the after shots with make-up and some fairy lights?”

“Oh absolutely, we love to have before and afters for our website. Without your face obviously.”

I strip off down to my skin and face the mirror.

I have been learning to live with my G-cups for three years now after being a size C for most of my 20s and 30s, yet I have spent very little time looking at them. I’m not averse to stripping off for impromptu dance parties with my daughter, yet standing in front of the mirror in this soulless square room feels nothing like dancing to Shakira around the living room in my knickers.

Thankfully, Dr Paul’s gaze is hygienically objective and I am saved from any further self-analysis as he skips the small talk.

“Your right shoulder naturally sits a little lower which makes sense, as your right breast is significantly larger, did you know that? It’s very common.”

His manner is weirdly anaemic, reminding me of that actor who plays Marty McFly’s teenage dad in Back to the Future. Sort of pleasant with waxy undertones.

“Yes, so, both your breasts are heavy with very dense breast tissue and must be causing you increasing amounts of discomfort.”

He lifts both boobs in turn. “You’ve got several acrochordons underneath both breasts caused by friction.”

“Excuse me?” Did he just tell me I have spiders living under my boobies?

“Skin tags.”

He points a latex finger at the gargantuan skin tag sitting between my breasts that won’t come off despite my best efforts to strangle its blood supply.

“You’ll find that all of the skin tags including this larger one here just won’t be a problem once friction has been removed.”

I picture these little pink papules fleeing from my body once their moist friction-y home has been sliced away.

“At an initial estimate, I’d say we’ll remove at least half of your left breast and maybe two-thirds of your larger right breast, so that’s around 600-700gms respectively.”

My brain immediately converts it into baking and I can visualise four blocks of Mainland salted butter stacked on the bench, prompting me to emit a surprised “Jeepers!”

He gives a soft dry laugh. “Yes, it’s rather a lot. This procedure is the surgical team’s favourite as the women who have it wake up with an immediate result from something that can be, or is, extremely debilitating.”

“And we would make the incision here,” he continues, running his finger along the underside of my breast, “up to the nipples then around the nipple.” He accompanies this with a roundy-roundy motion of his finger on my right nipple. “Then we’d remove the tissue and also perform a lift, which will help with the emptiness up here.”

He gestures at the tops of my breasts and he’s right, there is an emptiness to behold, a pale expanse of flat chest where bumps should sit.

“Huh that’s funny,” I say in an unfunny voice, “I’ve always wondered how to explain my boob deficit to people and that’s pretty perfect.”

“It’s a real benefit of this procedure,” he says. “We can reduce the size of your breasts and also perform a mastopexy so your nipples will sit about … here.” The location he is pointing to seems miraculous. I can’t believe this isn’t something I’ve considered till this exact moment.

“Are you saying that you’re going to give me a breast lift?”

I would later read on Dr Paul’s website that in a mastopexy, “the areola is centralised over the area of breast prominence where it would typically be in youthful women with smaller breasts”, which feels savagely honest and painfully reductive in equal measure.

It’s a lot to take in. And finally: “Now Emma, what cup size would you ideally see yourself as?” I want to scream SMALL, I WANT TINY GODDAMN TITS into his face. Instead I smile benignly. “I think a D cup would be sensible.”

I was 42 when my partner and I had a baby, after a number of years spent trying. I started eating almost constantly as soon as we had our first pregnancy scan at about four weeks.

I knew that eating pure shit for nine months wasn’t very clever, but the fact remained that all I really wanted to eat was brioche and supermarket frozen mince pies and eggs with sides of sweaty bacon. As a result, I gained nearly 40kg during my pregnancy and even that’s a guess as I refused to be weighed for the last few months.

This was around the time I had a minor revelation: we DO NOT have to be weighed by health professionals. It is our choice whether or not to step on those scales and saying no can make you feel a lot better about your experience at the doctor’s surgery.

Once I birthed my daughter my weight fell a little but not by much, and my new G-cup breasts that had developed over the pregnancy months just never went away (they actually got way bigger during the breastfeeding phase). At first, I rallied furiously against this new shape. My steadfast refusal to inhabit a much bigger body led me to drastic diets that I had previously shunned as bad news for someone with my history of disordered eating.

Then I came to realise that my unhappiness with my body wasn’t going to just affect me any more. And I didn’t want my daughter to go through years of self-loathing and an unacceptance of her body like I did. I didn’t want her to hear me say unkind words to myself about my own body. I didn’t want her to hear me talk about diets or food restriction. And I never wanted her to feel unworthy of attention or love because of her size – no matter what that might be.

So, I unbuckled myself from the shackles of the diet industry. It was no quick fix. Just a relearning of how I regard the body I’m in and the acceptance that comes with that. And a refusal to ever put myself through a weight loss programme again. The data doesn’t lie – they don’t work for the vast majority of us.

However, the fact remained that I now had a very large pair of breasts that made it incredibly hard for me to exercise and move around comfortably. It was painful to wear huge bras every day and I ended up with deep grooves in my shoulders that never went away. I also started developing a small hump at the base of my neck caused by postural changes to accommodate the large mass I was carrying on my chest.

Then about six months ago I sat next to a woman at a dinner party and we got chatting about bodies and baby-bearing. She told me she’d had breast reduction surgery in her mid-40s and it had changed her life. Her small frame with H-cup breasts had made it impossible for her to live comfortably, despite the work she’d put into battling her eating disorder from which she was now in recovery.

In all my adult years I’d never, even for a second, considered surgery. It felt too much like a cosmetic luxury utilised by the wealthy quick-fix brigade. I had never conceptualised the physical limitations of what I was carrying around nor considered a world where this could be rectified with such a drastic step.

I googled the procedure and what I read told a tale strikingly similar to my own. “Breasts may be a source of social embarrassment and unwanted attention… many women will dress to hide the size of their breasts, and suffer from chronic rash or skin irritation under the breasts, neck and shoulder pain.” It was all so familiar.

Now, in his office, Dr Paul presses his palms together. “I’m going to take some pictures for your file, if you’re OK for me to do that?”

I have never taken a photo of my breasts, not for a sext, not for a laugh, not for a drunken moment best left forgotten, not for anything.

Yet here I stand with my wonky shoulders pushed back and my undefined areolas and my pedunculated skin tag on display, hearing the thud in my chest as Dr Paul adjusts his lights and then asks me to turn to the right then left and then centre, and on and on for a thousand years until the only thing I can see is my very large pale breasts and I’m scared if he doesn’t finish soon I’ll never think of anything else again.

Then suddenly we’re done. I sling my bra around my waist and do it up at the front before ungracefully dragging it into position with the clasp at the back. I’ve never figured out how to do it the normal way.

Later that night I continue with my research, and an article about teenagers and body image catches my eye. I think about my teenage self and the shame I wore on my chest. Shame that wasn’t mine to carry. Shame that stopped me from undertaking the most basic acts of self-care, like learning how to put a bra on with ease. Shame that has evolved into a deeply entrenched dislike for a part of my body that society tells me I should be showing off at every available opportunity. A shame that has followed me around in ill-fitting bras all of my life.

I want to pour a honeyed salve onto these old wounds and ease the hurt that my younger self went through. I want to start again and learn to love my 46-year-old body. I want to stand proudly in that soulless room for my “after” photos, and bear witness to the woman I have grown into, and all of the women who came before me.

I make the decision. I’ll find a way to cover the cost of going private. I book the surgery for August.

Author’s note: Breast reduction surgery is currently not publicly funded in this country unless you can prove to ACC that you are in enough physical pain due to the size of your breasts and that your weight sits under a certain BMI. I am in an extremely privileged position to be able to afford it privately and I want to acknowledge that, as I know that for thousands of New Zealand women, this is just not an option

Follow The Spinoff’s breast cancer awareness podcast Breast Assured on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider