When the n-word slipped out of former National MP Tau Henare’s mouth on national television last Sunday, Ātea editor Leonie Hayden realised she’d been harbouring a guilty secret.

I saw a video on Twitter a couple of weeks ago where Kendrick Lamar, who is playing here this week, stopped a white fan from rapping along with the n-word in one of his songs.

rip delaney @kendricklamar pic.twitter.com/GATaVPli5F

— taylor (@taylormprince11) May 21, 2018

And I thought, of course you can’t say that word, even in a song. Surely everyone knows that by now. Just don’t do it.

But then I saw a video of Tau Henare using it to describe Alan Duff during last week’s episode of Marae.

The thing is, I’ve heard Māori people use the n-word my whole life. Not just young people – my parents’ generation use it regularly. It’s used ironically, or fondly or as a placeholder for ‘bro’, similar to how it’s used in the US. It’s an affectionate nickname! I know two people that have an Uncle N*****!

Of course I know we don’t have the same relationship with that word as the US. It’s a different context entirely. There it represents generations of trauma; its reclamation is more meaningful to African Americans than it could ever be here in Aotearoa.

But it still got used here.

I’ve been called racial slurs but never the n-word. It’s not a word I use or feel I have the right to use but I never stop my friends or whānau using it. I do the mental equivalent of a shrug and I move on with my life. And seeing it slip out like that when Tau Henare used it made me feel like he’d exposed one of our secrets.

What if we’ve been using this word for years… and we’re not supposed to.

I really wanted to speak to someone from the New Zealand African American community, and I followed a lot of leads, but I didn’t have any luck. And I don’t blame any of them. It’s a hard kaupapa to talk about, and even harder to translate centuries of oppression into a quick take, which lends even more weight to the ideas eventually shared with me by Damon Salesa, associate professor of Pacific Studies at the University of Auckland and a Rhodes scholar who taught in the US for 10 years.

Leonie Hayden: Can Māori and Pacific people use the N word?

Damon Salesa: Well obviously they can, but there are real risks with that because you can’t decide what a word means or its history or what effect it has on other people. Māori and Pacific people live in a context where we have a very strong relationship with African American culture, and that’s the setting for many of the things that we do, whether it’s hip hop or dance or even some of the political movements we have, so if you’re going to use a word you can’t then say ‘this word doesn’t have a bearing on these other contexts that are meaningful for us.’ You can’t decide ‘I mean it this way and not that way’ when so much of what we do puts it in that [African American] context.

So I think the short answer is, really, that if you’re using it you must surely be aware that it’s perhaps the most powerful word in the language because it’s connected to this deep history of enslavement, of inequality not just in the past but in the present, and it’s one of a few words that can just, in an instant, have a palpable effect on someone. This is a world where people are still shot for the colour of their skin in the United States. Everyone knows it.

Words like ‘Hori’ and ‘FOB’ and ‘Coconut’ have been claimed here in the same way the n-word has in America. So if we have these words that have our trauma in them and subsequent generations have reclaimed them then shouldn’t that be enough?

You can never diffuse those terms. Even if you use it in jest within a group who shares context and meaning, people are listening on and people see. Even words like that, which don’t have anything like the power of the n-word, you can’t make safe.

In many ways there’s nothing as powerful in the language as the n-word because of its ability to offend people and to denigrate them, so that’s why there needs to be an extra level of care because you can’t ever remove the history of the word just by saying you meant it this way or that way. We don’t get to control the meaning and I think that’s the bit that people miss. It’s not up to you what a word means.

Does it matter that it is a word that has been used in this country against Māori and Pacific people?

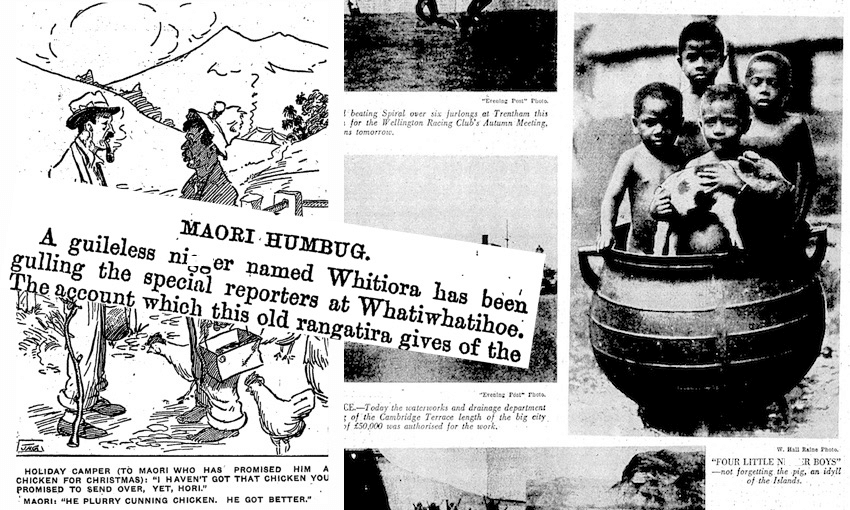

I think it matters. It’s worth reminding people that the US was not the only place that this was used by different kinds of oppressors. It was really common in the Pacific, it was most common in New Zealand at moments of conflict, like the New Zealand wars, so we should bear that in mind, that we’re making light not just of other people’s struggles, but of our own. It was used about Pacific people, especially Polynesian people when they travelled, and all the time it was used about people from the Western Pacific, people often called Melanesians, so it has a whole history of use right here in the Pacific and none of it was complimentary, all of it was harmful, and all of it was connected to real histories of oppression and the removal of peoples rights.

Even very powerful Polynesian chiefs were addressed by this word at times, and that is something that I don’t think many of us who’ve seen it in the past and seen how terrible that past was, want to bring it into the present. It simply can’t be washed out. Not by dozens of years and certainly not by trying to invert it saying ‘I was only joking’ because there’s a certain level of hurt and harm that can’t be done away with humour and irony.

It was used widely in the British Empire, not just about people of African descent, but about people from South Asia especially. In 1857 there was what was called at the time the Indian Mutiny, and is now known as the War of Independence, and this word was used widely and resulted in mass violence against South Asian peoples.

There are moments where you can build solidarity through that shared experience of oppression, but you don’t control that either, it can escape you and others can use it against you. This is one of the struggles in the African American community, is that some people don’t feel that word can ever be rehabilitated or controlled and that using it in jest is just really using it like other people do but in a more intimate way that’s actually your own agency. There is a real dispute amongst African Americans about whether that word should even be used on each other in closed groups.

Are we being too politically correct in policing language?

Humour has always been a way to tackle inequality and oppression and it’s one of what has been called the weapons of the weak, so humour has been used to invert things, but that goes both ways.

This isn’t about policing language, it’s about acknowledging the responsibility and power that comes with being a user of language, and also really about that deep sense of reciprocity that lives in most people’s lives in Māori and Pacific cultures – that [idea of] ‘is this the way I would like to be treated?’ When you’re in intimate groups and with people like yourself, that reciprocity is already there, it’s assumed and it’s safe, but words like this are so powerful that they’re never safe outside of any one particular context.

WATCH The Spinoff TV: Can Māori and Pacific people say the n-word?