The current standoff at Ihumātao has deep roots in the legacy of colonialism and land confiscation. Historian Vincent O’Malley writes about how it was taken by the Crown, and why that matters today.

The New Zealand Wars may have ended nearly 150 years ago. But their consequences continue to be felt today. Nowhere is that clearer at the moment than at Ihumātao. To understand what is taking place, we need to step back to the time of the Waikato War.

In July 1863 the Crown launched a premediated war of conquest and invasion directed against Kīngitanga (Māori King movement) supporters in Waikato and those of their kin who lived further north, around the shores of Manukau Harbour, at Ihumātao, Māngere and elsewhere.

These were the same Māori communities who had been feeding and protecting the settlers of Auckland for more than two decades. Earlier, during the Northern War of 1845-46, they had pledged to defend the township from possible attack. But now they stood accused by the Crown of plotting to massacre these very same Pākehā. It was a desperate lie, attempting to justify the unjustifiable – the Crown levying war upon its own subjects.

Those allegations were not only entirely unfounded but also illogical. Destroying the key outlet for their produce would have been suicidal for the Māori communities concerned. Their wealth and power depended, to a large degree, on Auckland’s ongoing wellbeing. It was a mutually beneficial relationship – at least until Governor George Grey decided that the Kīngitanga had to be destroyed, paving the way for the invasion of its Waikato heartland in July 1863.

In the days leading up to the planned attack, Māori communities at Ihumātao and elsewhere in South Auckland were driven from their land and forced to retreat beyond the Waikato River. An ultimatum dated 9 July 1863 was delivered to the people of Ihumātao and other settlements requiring them to take an oath of allegiance to Queen Victoria or immediately retire to the Waikato.

Some of those who received this notice understood it as an order to leave. Others feared that if they took the oath they would be forced to fight for the Crown against their own relatives. Only a handful of people agreed to pledge allegiance, some of them visitors from the north. When the ultimatum was delivered to Ihumātao on 10 July, the response was clear: they would join their kin in the Waikato.

They left with only what they could carry. Everything else was seized from them. The lands were subsequently confiscated, houses and property looted or destroyed, and horses and cattle seized by settlers for sale in Auckland. One settler later observed that ‘The Ihumatau [sic] natives…were good neighbours and very much respected by the settlers around; nearly all their houses and fences have been destroyed; their church gutted…their land…occupied.’ Generations of Māori were condemned to lives of poverty and landlessness.

Crown official John Gorst later wrote with respect to one group of Māori evicted from their South Auckland homes that ‘All the old people showed the most intense grief at leaving a place where they had so long lived in peace and happiness, but they resolutely tore themselves away. The scene, as described to me by an eye-witness, was most pitiable’. This was New Zealand’s version of America’s Trail of Tears. Except hardly anyone here knows about it, because we don’t learn this history in school.

Two days later, on 12 July 1863, British troops crossed the Mangatāwhiri River. The invasion of Waikato had begun. Many of the people driven from their homes at Ihumātao and elsewhere fought alongside their Waikato whanaunga in defence of the Kīngitanga.

A professional standing army belonging to the world’s greatest military power was unleashed on a civilian population that was heavily outnumbered and did not have the firepower and technology available to the British. In this asymmetrical war, the British had armour-plated steamers. Māori had wooden canoes and were outnumbered four to one. In these circumstances, the Māori defenders suffered casualties that were almost certainly greater in relative terms than those incurred by New Zealand troops during World War One.

In 1927 a royal commission found that ‘a grave injustice was done’ to South Auckland Māori ‘by forcing them into the position of rebels and afterwards confiscating their lands’. In 1985 the Waitangi Tribunal concluded that ‘all sources agree that the Tainui people…never rebelled but were attacked by British troops in direct violation of Article II of the Treaty of Waitangi’.

It added with respect to Ihumātao that ‘not only were the inhabitants attacked, their homes and property destroyed and their cattle and horses stolen, but then they were punished by confiscation of their lands for a rebellion that never took place’. In 1995 the Crown apologised to Tainui for ‘the loss of lives because of the hostilities arising from its invasion’ and ‘the devastation of property and life’ which resulted.

From the outset, the Crown had intended funding its war of conquest through seizing Māori lands as these were occupied, planting military settlers on some of these to consolidate its control and selling the remainder for huge profits. Around 1.2 million acres of land was confiscated, stretching from Auckland all the way to the northern boundary of the King Country, a few kilometres beyond Kihikihi.

An area of 1100 acres was confiscated at Ihumātao, 260 acres of which was eventually restored to Māori deemed not to have engaged in, aided or abetted acts of ‘rebellion’ against the Crown. The rest was sold to settlers, including an area known as the Ōruarangi block that was granted to Gavin Wallace in 1867.

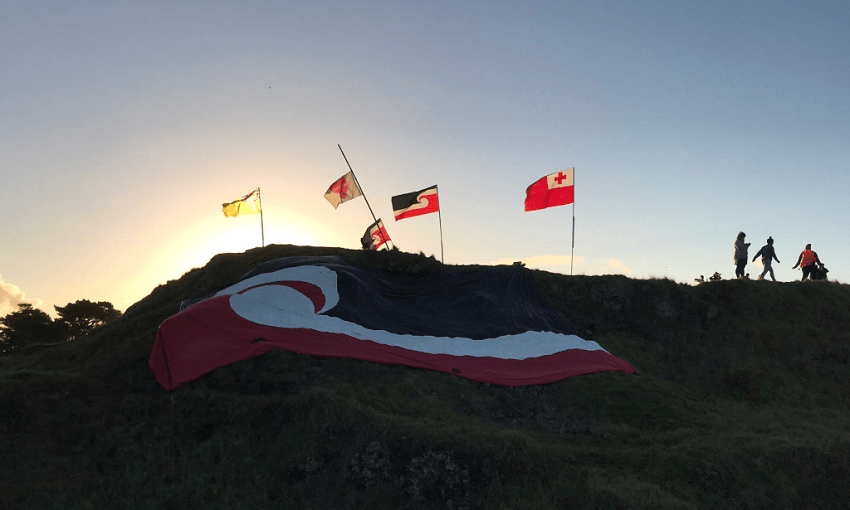

In 1999 Manukau City Council, Auckland Regional Council, the Department of Conservation and the Lottery Grants Board jointly purchased a 100-hectare site from several owners and two years later the Ōtuataua Stonefields Historic Reserve was officially opened. The lands adjacent to the stonefields reserve remained in Wallace family ownership until being sold to Fletcher Residential Ltd in 2016 after being rezoned a special housing area. It is this area that is the focus of current efforts by SOUL (Save Our Unique Landscape) to prevent 480 houses being constructed on the site.

In the 20th century, the construction of Auckland airport and nearby sewerage works caused more harm to those Māori who had returned to settle on a small fraction of their former lands. Those issues were reported on by the Waitangi Tribunal in its 1985 Manukau Report, which concluded that ‘The policies that led to the land wars and confiscations are the primary source of grievance, although they occurred last century. It is the continuation of similar policies into recent times that has prevented past wounds from healing.’

It is only through understanding of the historical context that we can fully make sense of the present. From whatever angle the current controversies are viewed, it seems clear that the legacies of Crown-directed invasion and dispossession against tangata whenua remain at Ihumātao today.

Vincent O’Malley is the author of The Great War for New Zealand: Waikato 1800-2000 (2016) and The New Zealand Wars/Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa (2019), both published by Bridget Williams Books.