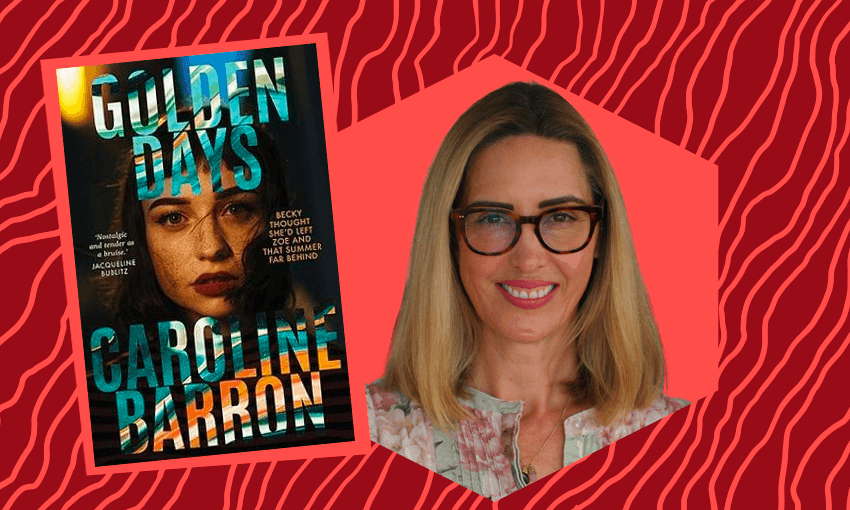

Sam Brooks reviews the local thriller that (briefly) unseated the new Eleanor Catton from the top of the Unity Book Charts, and finds it, well… thrilling.

I say with full compliments that when I got about halfway through Golden Days, I could tell that it would have a “reading group questions” section at the back of it. The new novel from award-winning memoirist Caroline Barron (Ripiro Beach) is the kind of gripping page-turner that feels ideal for a book club. Not only is it a quick read – it took me the slimmer part of an afternoon – it asks pointed, difficult questions about friendship, the uneasiness of shared trauma and the human capacity for self-deception. Fun stuff, and even better stuff to debate around a cheeseboard over a few chards with some mates.

But first, the actual book. In the first few pages, Becky’s slightly-less-than ideal life (a one-time writer who makes ends meet as a copywriter) is upended when she finds out that her husband has been cheating on her with one of her coworkers. As she drinks her way through it, a letter arrives from Zoe, her best friend from uni. Their friendship, struck up at uni and carried through the mid-90s, amid, as the book’s rear cover says, “the backdrop of Auckland’s burgeoning party scene”, is slowly parcelled out throughout the novel, as is its dissolution.

Based on that description, it seems odd to call Golden Days a thriller, but it got me turning the pages like it was. It feels far more relatable, closer to the bone, than a political or espionage thriller does. A secret agent being held hostage in a foreign country is a bit scary, sure, but pretty much everybody can relate to the gut-drop feeling when someone you thought (hoped?) would never show up again suddenly does.

Without spoiling the book’s sleight of hand – although it’s hardly a spoiler to say that “everything is not as you initially assume” because that’s the basis of most good storytelling – Barron shows us the limits of perspective, especially when it comes to something as subjective as friendship. One party can remember a slight as a deeply hurtful insult, accidents can be interpreted as deeply intentional wounds, and so much turmoil can exist in the grey areas.

Barron is a great storyteller, and it’s a credit to her that her twists and turns don’t feel like an author intentionally playing with her readers, trying to shock and surprise them, but like an acknowledgment of the psychological walls we build around our own trauma, and our role in it. Where she’s even better, and probably why this book is so successful, is her gift for a visceral image. Take this description, of an all-timer of a hangover:

“My skin is even paler than usual, my freckles a haphazard splatter. Even worse than the purple pouches beneath my eyes is that I can smell myself: the musky sebum of unwashed hair and the tart note of underwear that needs changing. My skin feels dry and dusty but crevasse-sticky, all at once.”

These images recur throughout the book, and it’s where the writing is strongest; making very common experiences feel that much more present, that much more full of blood. It’s not that any of us have necessarily had the same experiences as Becky, but Barron taps into those near-universal images to illuminate hers. Extra credit has to go to her description of an especially terrible art opening, which truly captures for the first time in my memory how absolutely soulless and gross those things can be; all surface, all skin, no substance.

Interestingly, the book serves as an odd companion piece to, of all things, Pip Adam’s award-winning novel The New Animals. While it doesn’t have that novel’s ambition or surety of outré craft, they exist in the same milieu. The characters at the heart of Adam’s book felt exemplary, standing inside their scene while managing to raise their eyebrow at its participants from the outside. They would have rolled their eyes at Becky and Zoe, would have despaired that the men in their community entertained the presence of these girls, and marched back onto their own self-obsessed dramas. Golden Days, however, shows us two girls in thrall of those parties, and two women who look back on that thrall in two very different ways. It’s a bit more soapy – there’s at least one twist that Shortland Street has done once or thrice – but that feels appropriate for both the milieu and these characters; they’re the kind of people who say “god, I hate drama” with zero irony, sitting in the eye of the drama’s storm.

One of the disembodied, probably publisher-mandated, reading group questions at the back of the questions asks: “Can you think of a time when you have actively reshaped your past to appear a certain way to certain people?” (Can I think of a time when I haven’t, disembodied question!) On the surface, Golden Days is an entertaining page-turner. Not too far below that surface, it’s a story that shows us two scabs on two different bodies. One character has let that scab turn into a scar, the other has picked at it daily without knowing, bleeding a bit more every time. In its best moments, it invites the audience to think about whether they’re scarred or bleeding.

Golden Days by Caroline Barron ($38, Affirm Press) can be purchased online and in store from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.