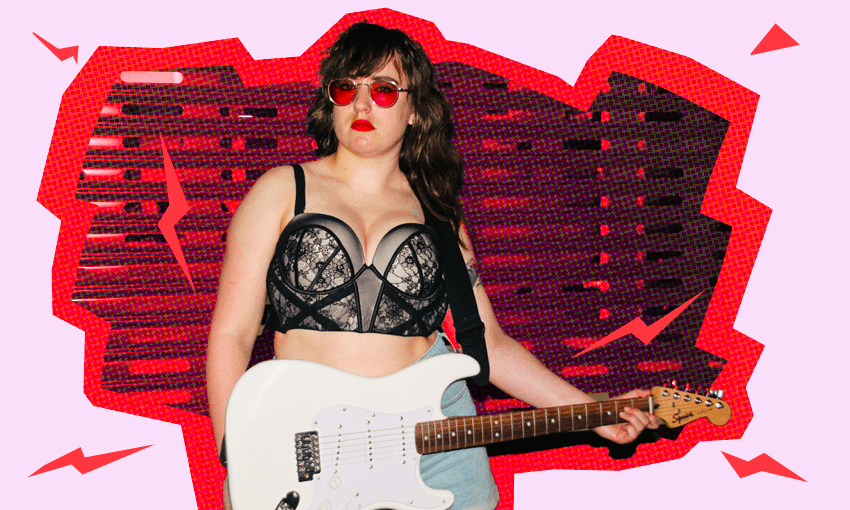

Poet and theatre artist Freya Daly Sadgrove talks with books editor Claire Mabey ahead of Freya’s new poetry-in-performance show Whole New Woman.

Claire Mabey: You just opened a gig for Peaches here in Wellington. How did that happen and what was it like?

Freya Daly Sadgrove: How it happened is Nathan Joe. I am his baby and he nepo-babied me. We’ve worked on Show Ponies together and he’s the Creative Director of Auckland Pride and when he was asked by the Peaches people for suggestions of opening acts, he was like hmmmm time to push the poetry agenda!!! That’s what I imagine he was like anyway. He put my name forward, and I just think that was so dope and interesting of him? I don’t know, it’s just not something you expect to be asked to do when you are a poet, let alone when you’ve spent most of your life in Wellington and are, you know, used to a sort of smallness. Open for Peaches. I feel like Nathan’s thinking of a really big picture of the arts – presumably because he’s making and supporting work in so many different places and forms and ways. I Love And Respect Nathan Joe.

The experience itself was fucking magnificent. For one thing, I hadn’t performed for almost a year, really, and I just… you know, I just… it’s embarrassing for me (only cos of society) but the best thing I like to do is prance around on a stage saying exactly what I mean while my talented friends have a big hoon on their instruments. Samuel Austin was playing the drums and it’s just so fun to share the stage with him. And we got to do that for like, 20 minutes! And I don’t think anyone got bored! Some of them even bopped! And I felt fucking alive lol. So it was a very huge and usefully-timed reassurance that my show probably isn’t gonna suck too hard, which obviously has been a worry obviously.

But the massivest thing about opening for Peaches was seeing Peaches perform. I am not exaggerating when I say it was life-changing. I was open-mouthed the entire time. The craft!!!! The commitment!!!! The total absence of boundaries!!!!

You’re behind the electrifying genius that is Show Ponies, a kind of poetry cabaret where poets perform with back-up dancers and live music. It’s transformed the way audiences can access and experience poetry. Is the style and format for Whole New Woman riffing off Show Ponies?

Yes, big time. The first time we did Show Ponies it was like, oh true, we can do anything we want. It’s properly a vibe for the audience. There’s totally room to go bigger and push harder. Kirsten McDougall who was the publicist at THWUP (VUP at the time) was like well hey Freya you could make a whole show out of what you’re doing there in your set, and I was like oh shit true ok yeah cool I’m on it.

Then lockdown happened and time passed and covid covid covid. And my mental health stabilised and my thoughts progressed and my horizons widened, so my idea of the show kept growing, with nowhere to become real. It was hard to know where to like, stop the transformation represented in the show because time kept passing and I kept transforming IRL and getting new things to say and ways to say them. But you can’t say everything in one show. Anyway I’m off track fuck. Certainly it’s always been growing from the seed of my first Show Ponies set, alongside Show Ponies’s own evolution, but secret and unperformed.

Whole New Woman is a solo show and something you’ve been working on for a while now, can you tell us what’s it about? What’s the vibe?

I don’t know if it can really be called a solo show, even though it’s very like, Me Me Me the Big Freya Show. But there’s two people with me on the stage the whole time – Samuel Austin (drummer) and Ingrid Saker (guitarist) – and they’re very much present, they’re very much doing a big powerful thing that actually makes the show. I’ve known them both for a fucklong time actually, over a decade. We’ve all done theatre together before, in quite foundational times in our lives, and it’s pretty special to be getting back on the stage with them now in this new context.

And yeah, I’ve been working on it for over three years lol. It’s evolved massively over that time. To begin with it was gonna be Head Girl: The Show, an extension of me and Thomas Friggens’ Show Ponies set – a kind of Show Pony-ified stage adaptation of my book. The plan was for that to go up at BATS in April 2020 and then go to Edinburgh Book Fest, lol, lol, lol, RIP. But I wrote Head Girl over like 4 or 5 years in my very mentally ill twenties, and I was already looking backwards at it when it was published; I was already new and different by then and ready to move ahead, so the show had to shift somewhere new too.

It’s not like completely out the gate new though, the vibe is still mental illnessy as – but still in a cool fun interesting way imo. It’s definitely to some degree responding to the book. It’s about transformation. It’s also about consciously trying to throw off that lifelong goddamn shame of asking to be seen and listened to, which currently has me by the throat. You might not necessarily suspect that if you have seen me perform lol, but that’s legit the only time I get free of it.

So Head Girl is your first collection of poetry, can you tell us more about how you’ve woven that material into Whole New Woman?

There’s seven poems from Head Girl in the show. I have on-and-off worries that I’m flogging a dead horse. Especially when I am “learning my lines” I’m like good lord can I let this poor sad period of my life rest, but when I am rehearsing the performance of them, I’m like ah, there is still some power here, and certainly there is meaning I want to draw from and reflect on and reframe from a new perspective. And the show is about transforming into a Whole New Woman, and without the context of the Old Girl that transformation wouldn’t land as hard I don’t think.

And so, yeah, the show transforms as well. The form of it transforms. Basically I’m pivoting to rockstar? For my thirties. I have written some songs. We are performing some songs. I am terrified to fucks. But also I’ve recently become very very powerful and I can totally actually do it I’m pretty sure.

Creating a live performance show is obviously a lot different to writing a poetry collection: how does the process differ? Do you enjoy one more than the other?

It definitely is different, but actually because of the panny d and various cancellations and delays and shit, I’ve spent a freaking lot of the past three years thinking about and writing this show in isolation, which is pretty similar to how I wrote my book. Similarly, at points it drove me a bit fucking mental. The thing that saved me each time was yanking my head out of my navel (or was it my ass) and talking it out with people.

So then actually getting to be in a room with my collaborators is only ever a joy. I have the excellent fortune of knowing and working with musicians and theatremakers who are really on their shit, really generous, really fun, kind and funny, and importantly beautifully accepting of my chaotic vibe. I feel so good and chill and stoked to work with everyone who’s been involved, man, it’s everything. I definitely enjoy that way more than sitting angsting in a room by myself and sweating out one word every forty minutes, yeah.

Do you prefer to encounter poetry as a performance? Do you think more people would love poetry if they saw it performed live more often?

Weirdly I’ve never asked myself this question before. I suppose, yeah, I do prefer it – even poetry on the page I prefer to experience by reading aloud. Cos like, sound, you know? It’s essential to poetry. Can’t finish a poem without reading it aloud.

In year 12 Mr Watson read aloud from The World’s Wife by Carol Ann Duffy and I was like ohhh shiiiit. Like damn, he knew how to read poetry. I still read those poems with his cadence; the rhythms of Little Red Cap and Mrs Quasimodo and Mrs Beast are all tattooed into my … er, soul? They’re definitely tattooed somewhere. Fuck I loved school lol fuck.

Yeah… I’d be lying if I didn’t say Show Ponies is my favourite way to experience poetry. I’d be lying if I didn’t say every poem performed in every Show Ponies show hasn’t moved me like… all the fuckin way. And enough people have said to me that they didn’t get or care about poetry before they saw Show Ponies that I feel pretty confident that yes people would love poetry more if they saw it performed – really performed – yeah.

I first performed my poetry when I was 11 lol. I got wheeled onstage in a wheelbarrow and I wore pajamas and a top hat. Wow… not as much of a Whole New Woman as I think.

You’ve been wonderfully honest in the past about how difficult it can be trying to be an artist in New Zealand. What would make it feel less demoralising do you think?

Okay doing Show Ponies in Auckland for Pride and Samesame But Different was like, extremely undemoralising, and the reason was: I had a real producer. I.e. not just me flying by the absolute seat of my pants, trying and failing to know what I’m doing the whole time. And that producer, Izzy (mononym, powerful), also procured a team of several people to do what I have been attempting to do in various degrees of alone-ness with Show Ponies for over three years. Tears come to my eyes to think of it!!!

I’ve never had enough funding to pay a proper producer, only enough to underpay me to produce (because I’m not a proper producer and I’m always lowballing my funding applications). I won’t do Show Ponies again without one, because I can’t go back now. The whole week leading up to the show I was going, how on earth do I feel this mentally okay? This has never happened before. I think a lot of artists accept a fairly high degree of mental fuckery tryna make stuff, because how else will it get made? But then I had Izzy going, Freya it does not have to be like this, I am here to look after you and the show, I don’t think artists should have to feel destroyed by their work. So, what would make being an artist less demoralising in NZ? More Izzys. How do we get more Izzys? Perhaps there should be (more?) specific arts administrator funding/training/mentoring/databases/community-building. Not all artists hate producing, but fuck, it’s not in my wheelhouse, it’s not where I feel confident. Where I feel confident is in the dreamy thoughty weird chaotic art-making artist-feelings-nurturing place, and the art is not as good when I can’t afford to spend time there.

But yeah, Izzy working on the show and getting that team together was possible cos of funding. It’s always funding, obviously. This time most of that funding came directly from the community – through the crowdfunding campaign that Nathan Joe absolutely busted his ass to make successful – Pride Elevates. Oh funding. Just… you know. Govvy baby… can u chuck more money in tha arts pls and a UBI thanks x

What are your hopes for Whole New Woman?

Do it again, for sure. Tour it. Make it bigger. Get backup dancers. Do it with three drummers onstage. Not kidding. I feel like it’s got some legs. Also my hopes is, while it goes around on its legs, that I can also be doing something the fuck else. I been living with this show in my head for so fucking long and I have more new shit to make. I have ideas!

Imagining you’re being forced to convince someone who a) says they hate poetry; and b) also isn’t into theatre; how would you try and convince them to give your show a go?

To toot my own horn (or to absolutely own myself, can’t tell which) a lot of people have told me they don’t like poetry but they do like mine. So, suck on that for one thing. I’m a gateway drug baybee. For another, the theatre aspect is really just that it’s in a theatre. I’d say, do you like live music? Do you like badass people going hard? Do you like Sam Duckor-Jones’s visual art? Do you like a really interesting cool time???? This show is not like other girls. (However it is in a community with other girls and loves and respects other girls and will help you to love and respect other girls too).

Whole New Woman by Freya Daly Sadgrove is playing at BATS Theatre on 9 – 11 March (currently sold out but worth trying your luck on the door). You can purchase Head Girl by Freya Daly Sadgrove (Te Herenga Waka University Press, $25) from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.