Book of the Week: Jane Stafford reviews a vast, thought-provoking study of late colonial New Zealand, when European portrait artists romanticised Māori culture.

I have long regarded Roger Blackley as a living taonga, an unfailing resource for anyone working in the field of Aotearoa New Zealand’s colonial culture. There is no enquiry too recondite, no reference too obscure, no detail too small for him – and any query will invariably be answered with precision, with wit, and often with a bit of olden-day gossip thrown in.

His book Galleries of Maoriland is a reflection of this scholarship. It’s a vast, all-embracing, minutely detailed yet highly readable book, beautifully designed with clear images, often full-page, always exactly where the text needs them. It’s much more than a work of art history; it’s a complex and thought-provoking cultural history of late-colonial New Zealand, Māori and Pākehā, using art production, reception, collecting, and ethnography as a way of understanding that period referred to as “Maoriland”.

Late-colonial Pākehā society adopted – or appropriated – a highly romanticised form of Māori culture as a template for settler identity, the implicit justification being that the original owners were now extinct or heading that way. Blackley’s narrative sets out the parameters of Maoriland, demonstrates many of its mechanisms, but also extends the way the term has been used, then and now, by suggesting that important players of the Māori world participated and exercised agency within its confines.

Through this focus, we are given a picture of a multifaceted world – scheming, grasping, acquisitive but also deeply bicultural, idealistic, and, on its own terms, scholarly, although some of the conclusions of that scholarship might seem now a tad barmy. Much of its basis was commercial – artists might have idealistic principles of art for art’s sake, but they were also businessmen (usually but not invariably men) and active players in the commercial life of the colony. Collectors might be motivated by scholarship and aesthetics but were also acutely aware of the monetary value of what they collected.

Blackley’s canvas is broad. There are discussions of the representation of Māori in local and international exhibitions and in model villages; of moa bone hunting and theorising; of “fossicking”, the bland and seemingly innocent term for the disturbance and desecration of Māori sites and artefacts; of the relation between the Land Court and portraiture, and more. Whatever the focus, we see a mix of interaction, exploitation, and admiration, of crass, offensive ignorance and deeply respectful knowledge – at times combined in the one person, as in Walter Buller, who, Blakely states, displayed “both an erudite understanding of Māori values and a brazen capacity to violate them”.

He avoids the moralising hindsight of some postcolonial criticism and avoids the flattening and reductive effect of postcolonial theorising. He’s aware of and empathetic to Victorian values and perspectives while identifying their pernicious effect; he’s equally aware that Maoriland is a society in which the underlying narrative is one of cultural depredation and land loss. But his argument, supported with a wealth of evidence, is that, while we should not indulge in an overly celebratory account of subversion and fight-back, it’s not correct to see Māori as disempowered victims.

This central position is nicely illustrated in the discussion of Māori attitudes to portraiture. Blackley sets out a “spectrum of attitudes … ranging from whole-hearted acceptance – associated with a realisation that one could thereby exert some degree of control over one’s image – through to outright abhorrence and rejection”.

Te Whiti refused to have his portrait painted or photograph taken – which didn’t stop his creepy post-Parihaka jailer and would-be best friend John Ward from surreptitiously photographing him and publishing both the photographs and a gleeful account of his deception. At King Tawhiao’s tangi, efforts were made to prevent photographs of his lying in state – unsuccessfully. As Blackley notes, small portable cameras now made surreptitious images possible. The distaste may have been in part cultural but there is also evidence of a quite modern dislike of the commodification of one’s image by others. Ngāti Maniapoto chief Rewi Manga Maniapoto ‘refused a photographer’s request to take his photograph, “saying it was not proper for a great chief’s likeness to be sold for 1s [shilling]”’.

The commercial galleries of Maoriland were visited by both Pākehā and Māori, and Māori had decided opinions on the art that represented them. Māori might commission portraits but also argued about the price and disputed the accuracy of the likenesses. The widely reproduced 1898 painting The Arrival of the Maori in New Zealand was disliked by Māori for its skeletal, unheroic forms. The Lindauer Art Gallery had a Māori visitors’ book in which comments and judgments were recorded.

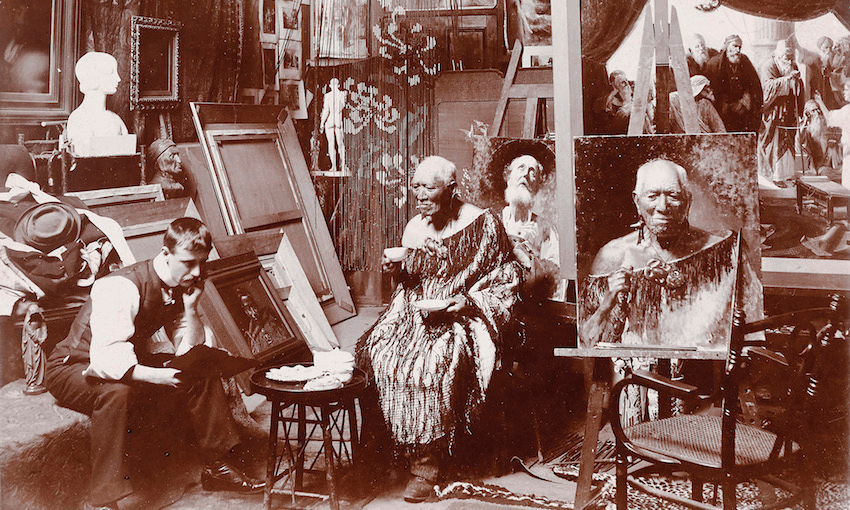

Many important figures in the Māori world saw having their portrait painted as an indication of status – although this very European activity was still framed by Māori protocol. It was important that rules of tapu still be observed and that the painting as object be treated with the dignity and veneration appropriate to its subject. There’s a lengthy and fascinating discussion of the two forms of portraiture which figured in the careers of Gottfried Lindauer and CF Goldie. Blackley distinguishes them in terms of each artist’s relationship with his models. Lindauer’s highly realist portraits were commissioned and paid for by their Māori subjects; in Goldie’s case, Māori were employed as models.

Goldie’s portraits don’t pretend to documentary veracity. They are genre paintings, having an implied narrative, usually one of subjection. Goldie’s subjects are elderly, pictured in attitudes of abjection, surrounded by a mix of Māori and European markers – a heitiki, a plaid blanket.

And yet Blackley shows that Goldie’s models were important figures in both Māori and Pākehā worlds, sophisticated players with whom Goldie had close relationships. And Blackley points to the importance that Goldie’s portraits have for a Māori audience – in the nineteenth century and now – who look through what we might see as the artifice and sentimentality of the frame to the person, recreated and immediately, unnervingly present.

I don’t care for Goldie. But I admire Blackley’s insistence that we see his work on its own terms. I can’t quite agree with Blackley’s suggestion that, far from being in the dying-race-last-of-his-tribe tradition, these pictures point to the merging of Māori and Pākehā in the future, “transformation not extinction”. Colonial intellectual systems are confused and contradictory and certainly some commentators argued that the future New Zealand would be a fusion of the best qualities of each race through intermarriage – the sturdy Anglo-Saxon and the spiritual Māori. But is this theory implicit here? The dying race myth in this period was rarely meant literally. It conveyed, rather, the death of culture, memory and knowledge, cultural extinction, or acted as a wider metaphor, applicable to Māori and Pākehā alike, for the losses involved in modernity. There’s always an acute and exaggerated sense of the passage of time in colonial culture because the human presence is so tenuous and the landscape has been changed so quickly and so radically.

Authenticity was key to the galleries of Maoriland – and, to paraphrase George Burns, if you can fake that, you’ve got it made. Māori were often required to enact a version of authenticity at odds with being actors in the modern world. The project wasn’t helped by the insistence of Pākehā commentators as to what was and wasn’t authentic. Lindauer’s portrait of Rewi Maniapoto was based on a photograph in which Maniapoto’s shirt collar and waistcoat are clearly seen. The portrait nevertheless pictures him in “timeless” Māori dress. Māori were pictured as properly occupying “archaic space” – a useful placement, as it meant they were out of contention when it came to political power, land ownership, or the possession of significant taonga which the late-colonial Pākehā world increasing saw as curios and collectibles, commodified rather than contextualised.

Perhaps there was no area where the clash of cultures was more obvious than gifting. During the 1901 royal tour, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York were showered with valuable, historic and highly significant objects which were accepted with indifference. The understanding that in many cases objects were gifted to be returned escaped the royal recipients. There was a nasty scene in 1972 when the Duke of Windsor died and Māori donors applied for the return of two mere he’d been given in 1920. In 2018, the New Zealand Government’s wedding present to Prince Harry and his bride was a donation to a local charity – a much better idea and one not dependent on the cultural sensitivity of the recipients.

I keep returning to the photograph at the frontispiece, Steffano Francis Webb’s Doorway at the Tourist Department Court at the Christchurch Exhibition, 1906-7. What we can see of the room is modern and oddly provisional in that colonial way of everything looking like a hastily built stage set. There is a tongue and groove wall, wrinkled wallpaper, scuffed lino on the floor and a looped, fringed velvet curtain on a metal curtain rail. At the centre is the door, framed by carved panels. The carvings have a mesmerising strength and luminosity, not at odds with their surroundings but dominating them.

It reminds me that, during this period, Māori became Victorian, just as Pākehā became bicultural. The pre-contact context of these panels is not recoverable – to attempt to do so is to run the danger of re-entering a Maoriland fantasy of model villages and exhibition tableaux. But in the colonial context, Galleries of Maoriland suggests, their power was not negligible.

Galleries of Maoriland: Artists, collectors, and the Māori world, 1880-1910 by Roger Blackley (Auckland University Press, $75) is available at Unity Books.

If you have an iwi Māori perspective to share on this review, please get in touch: info@thespinoff.co.nz