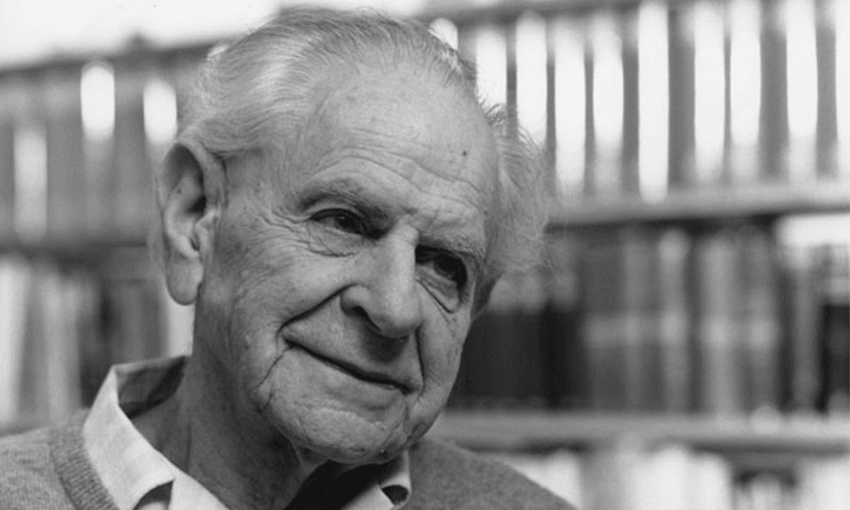

Karl Popper, 20th century philosopher, was a defender of free speech and a believer in the vulnerability of democracy. Dr James Kierstead and Dr Michael Johnston from Victoria University of Wellington discuss Popper’s politics and the relevance of them today.

In March 1938, a little-known Viennese philosopher called Karl Raimund Popper arrived in Christchurch to take up a position at what was then Canterbury University College of the University of New Zealand. By 1945, he had left for England and another appointment at the London School of Economics. In the meantime, he had written a book, The Open Society and its Enemies, which Michael King called “the most influential book ever to come out of New Zealand”.

Popper loved New Zealand (“the best-governed country in the world”) and New Zealanders (“decent, friendly, and well disposed”), even if students like philosopher and historian Peter Munz remembered him as an ornery presence. But despite the global impact his ideas have had (not least through the Open Society Foundation of another student, George Soros), Popper is not much of a presence in New Zealand intellectual life. We think this should change and that Popper’s political ideas still have a lot to say to us, particularly right now.

First, Popper’s political thought rejected authoritarianism of both the right and the left. A Jewish refugee from Hitler’s Germany, he was equally opposed to Soviet-style communism (which he foresaw would be increasingly influential even as he was writing The Open Society). For Popper, both styles of authoritarianism made a crucial mistake in seeing politics as a one-way street leading to a destination where discussion and compromise would no longer be needed.

What was needed, he thought, was a politics of continual and often minor adjustments to the way things were, always in response to what people wanted. This is the second idea we want to highlight: politics as “piecemeal social engineering”. Popper knew that big, wholesale changes looked tempting, but could often lead to major harms. To him, politics was like science: a way of constantly trying out new ideas, then jettisoning the ones that didn’t work.

As someone who lived through the German Reichstag’s vote to hand over power to Hitler’s cabinet, Popper was acutely aware democracy had an Achilles heel: it could vote itself out of existence. He called this “the paradox of democracy” and also warned of a “paradox of tolerance”. This second paradox has been widely misunderstood, and has even been used in attempts to stifle free speech. Popper’s point wasn’t that we shouldn’t tolerate ideas that some might consider intolerant; he thought we should be open to all sorts of ideas. What we shouldn’t tolerate are attempts to shut down debate “by the use of … fists or pistols”. These two paradoxes together make up the final idea we want to highlight: that the principles of liberal democracy are tolerant but substantive ones, and ultimately need to be defended if we want to keep on living our lives in political equality and freedom.

Popper’s insight about the potential for democracy to be vulnerable to its own mechanisms – to being “voted out of existence” – is one we would do well to heed in the present political moment. Unless it is safeguarded by deep understanding of – and fidelity to – underlying democratic principles in the body politic, the institution of voting will not, of itself, long support the continued existence of democracy. Democracy relies on a set of cultural values and customs; elections do not define democracy and neither are they enough to support it on their own.

An essential cultural value for the survival of democracy is reverence for free speech. If free expression is suppressed, public debate is deprived of potentially powerful ideas, especially if those ideas initially appear unappealing, threatening or offensive. Neither Darwin’s theory of natural selection nor the notion that women ought to be afforded the same political rights as men is controversial today, but when they were first proposed both were widely considered outrageous. Even so, once articulated, both ideas eventually won widespread acceptance, despite initially facing fierce opposition. This is at least partly because they arose in cultures that valued free expression.

There is a price to pay for the cultural dynamism and political liberty made possible by free speech: the expression of ideas that are genuinely bad, offensive and even cruel must also be allowed. That is because until an idea has been fully articulated, debated and tested – that is, subjected to the process that the principle of free expression makes possible – it is arrogant to think we are in any position to decide on its quality.

Some ideas are truly ill-motivated; hate speech is a genuine phenomenon. But even hateful ideas are best exposed to the light. Such ideas come from resentment and fear – from places of psychological ill health. If those who express hate are censored, they do not simply stop having hateful thoughts. Instead, relegated to the shadows, they become even more pathological, twisted by resentment born of repression – and all too often they later erupt back into the public sphere, armed with weapons instead of words.

As the second decade of the 21st century draws to a close, the world’s longest-standing democracies find themselves at a crossroads. Many western countries have restricted free expression with ‘hate speech’ laws, holders of controversial views have been banned from speaking in public venues and those deemed to be guilty of offensive speech find themselves banned from social media. Some academic journals and publishers have taken to rejecting, or even ‘unpublishing’ academic work, not on scholarly grounds, but simply out of fear that material may offend or run afoul of newly minted and ill-defined legal restrictions.

In one such recent incident, Emerald Press, based in the United Kingdom, reneged on the previously scheduled publication of a book defending the principle of free speech by the University of Otago’s Emeritus Professor James Flynn. Emerald Press cited “potential for serious harm to Emerald’s reputation and the significant possibility of legal action” as reasons for de-scheduling the book. It seems Flynn’s treatment of “sensitive topics of race, religion, and gender” – to quote from Emerald’s communication to him – were simply considered too hot to handle.

Some would argue free speech is really only at issue when governments seek to censor it through legislation. While legal concerns do seem to be a factor in the Flynn case, arguments like this miss the point: law tends to follow culture rather than the other way around. A democracy in which free speech is legally protected but no longer culturally esteemed is imperilled.

In a recent Spinoff piece about Emerald Press’s decision, Danyl Maclauchlan defended the publisher, arguing “there’s no freedom of speech argument that can force a private company to publish a book they don’t like”. That, of course, is true, but again misses the point. The fact is that by Emerald’s own admission it did not reject Flynn’s book because it doesn’t like it, or because it considers it lacking in quality. It rejected it because it is too intimidated by reputational and legal concerns to publish a scholarly book by an international expert. That, in our view, is a sign of a culture no longer conducive to the maintenance of liberal democracy.

How then might we preserve the cultural foundations of democracy in the face of rising fear and division? Education is one possible answer; ‘civics’ education is offered in many countries for exactly this reason. A free media is another. Both institutions are important, although it might seem we get the education system and media our cultural values support; our teachers and journalists and for that matter our politicians and judges are subject to the same social forces as the rest of us.

Liberalism and democracy, as Karl Popper recognised, rest on substantive values, values that have to be defended if liberal democracy is to survive and flourish. And it’s up to all of us to do the work of defending these values. If we say nothing while governments, corporations and ideologues threaten and quash the free expression of ideas, we are, at least tacitly, voting democracy out of existence.

Dr James Kierstead is a senior lecturer in Classics and Dr Michael Johnston is associate dean (academic) in the faculty of education at Victoria University of Wellington.