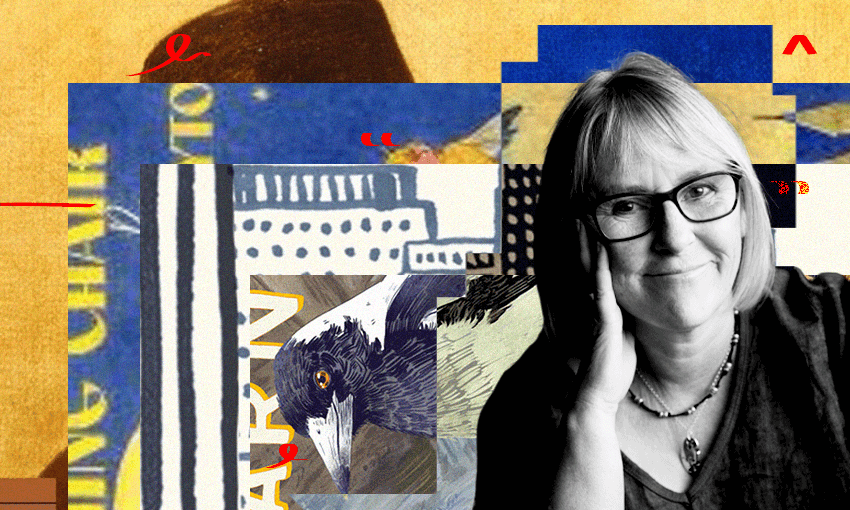

Welcome to The Spinoff Books Confessional, in which we get to know the reading habits of Aotearoa writers, and guests. This week: Claire Baylis, author of Dice and guest at the forthcoming HamLit programme at the Hamilton Arts Festival.

The book I wish I’d written

My mind seems surprisingly unwilling to rank books, and this first question make me consider how much a book is the product of its author’s worldview, background and identity – could I ever write someone else’s book? But that’s dodging the question so I’m going to plump for My Name is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout – I so admire both the restraint and the intensity of Lucy’s voice.

Everyone should read

How Many More Women? How the Law Silences Women by Jenifer Robinson and Keina Yoshida because it gives an international, big picture perspective on the multiple ways the law is used to silence those speaking out about sexual violence.

The book I want to be buried with

I don’t believe in an afterlife as such so I’m not choosing a book to reconnect with, instead I’m going with my novel Dice as a precious object of meaning for me – because it took me 50 years from when I knew I wanted to publish a novel to achieve that, and because even though it is utterly fiction it aims to reflect the lived experience of many real people – the jurors, complainants, survivors who I talked with, listened to in court, or read.

The first book I remember reading by myself

I must have read others before these, but I have strong memories of the act of reading: The Magic Wishing Chair by Enid Blyton because I had to hide it from my mum who disapproved even in the 70s of Blyton’s sexism and racism; and Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfield, which inspired me to audition for one of the children’s parts in the village production of Bitter Sanctuary by Rosemary Anne Sisson – I imagined being discovered. I didn’t fully understand the play, which is set in a refugee camp, but it certainly helped me understand the emotional power of language.

The book I wish I’d never read

The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy – because it was our assigned text in my first year at Central Newcastle High School at 11 and I was too young for it; it gave me the impression that the classics were ponderous and boring, and put me off reading them for years.

It’s a crime against language to

Suggest that books by authors from Aotearoa are not as worthy of your reading time – I mean WTF – there is such a breadth of incredible writers here in all forms and genres, so if you can afford to buy books, prioritise buying NZ to support our authors in this very small market.

The book that haunts me

Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter about the life of Buddy Bolden, a jazz pioneer in New Orleans. It haunts me because of the power and rhythm of Ondaatje’s language especially when describing the parade during which Bolden breaks down, but also the texture of the book – its collage of fragmented memories, interviews and historical documents – and now I want to read it again.

The book that made me laugh (and cry)

The Axeman’s Carnival by Catherine Chidgey – I was hesitant about a novel from a magpie’s perspective but was caught up by the end of the first paragraph, and found Tama’s voice hilarious, and subtly devastating as a portrayal of a coercive relationship from the perspective of a dependent.

If I could only read three books for the rest of my life they would be

Light the Dark: Writers on Creativity, Inspiration and the Artistic Process edited by Jo Fassler, a book of essays where writers describe the personal impact of favourite passages from literature – that would spark my own creativity and remind me of books by those authors and those they select.

Next, would be a book from one of the authors that was particularly important to me when I was first trying to find my voice as a serious writer – Alice Walker, Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Patricia Grace, Janet Frame, John Berger, Kazuo Ishiguro, Milan Kundera because any one of those would trigger memories from that intense reading period – today I’d go for Frame’s complete autobiography because it’s been a while …

And finally, Intimacies by Katie Kitamura, a quiet, taut book about an interpreter in the International Court in the Hague, which both stylistically and content-wise feels inspiring.

The plot change I would make

Had I written A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara I would have omitted the car accident because I couldn’t have written such an unrelentingly traumatic book. I struggle with the fact it’s become a BookTok teen favourite – I know some who have struggled as they read it, and feel you need maturity for this one.

Encounter with an author

When I was about eight, I went to an event where Roald Dahl was promoting, I think, Danny the Champion of the World. Mum and I waited in the very long signing line and presented him with my copy which I’d already read, only for him to refuse to sign it because it was not a new copy bought at the event. I’ve remembered that incident (and my mum’s fury) for 50 years, but I also remember writing to Elizabeth Gundrey, author of Collecting Things, about my collection of collections – bottles, shells, teeth etc and how she sent back a handwritten letter with a sheep’s tooth. Similarly, I remember Kirsty Gunn, soon after Rain was published, taking me seriously as a writer even though I’d only published a few short stories at the time. I know which kind of author I want to be.

Best thing about reading

As well as all the usual things about opening worlds and changing perspectives, for me, it is those moments of pure excitement when I’m stunned by something a writer has done in crafting their work. At 25 I was blown away by Lawrence Durrell’s use of perspective in The Alexandria Quartet and years later by Christos Tsiolkas’ in The Slap. I’ve been astounded by Alice Walker’s imaginary photos in Living by the Word, Cormac McCarthy’s meandering, shimmering sentences in All the Pretty Horses, by the subtle yet profound jump in circumstance in Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional, by Katie Woolf’s juxtaposition of verbatim accounts in The Haka Party Incident, and by the sheer power of Tusiata Avia’s voice, to name just a few…

Best place to read

The hammock, our deck, at one of the Rotorua lakes. But I also recently rediscovered the pleasure of audiobooks while driving when I listened to Elisabeth Easther’s beautiful narration of The Seasonwife by Saige England – a poetic, devastating story about the impacts of early European colonisers. I say rediscovered because we listened to audiobooks a lot with our children – including all John Marsden’s Tomorrow When the War Began series. And as a child, my parents taped themselves reading Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons series at night and then played it back to us, the tape reorder on the backseat between my brother and I, as we drove from Northumberland to see my grandparents in London.

What are you reading right now

I only read one novel at a time and that usually takes precedence, but I always have several other books on the go as well – poetry, short stories and non-fiction. I’ve just finished Colm Tóibín’s The Heather Blazing which I reread after doing some work with judges. I’ve moved on to Delirious by Damien Wilkins – his books are deeply psychological, funny and moving. Delirious feels very pertinent because I’ve been through the transition to retirement village living with my parents so I’m enjoying Mary and Pete’s perspectives on this, and they live on the Kāpiti coast where I’ve spent a lot of time.

I often read a poem to loosen my mind before I start writing and right now it’s The Girls in the Red House are Singing. Tracey Slaughter’s use of language and imagery in both her poetry and short stories is just extraordinary, so I’m looking forward to her talk at HamLit in a couple of weeks. Finally, my non-fiction current reads are Her Say by Jackie Clark and the Aunties and The Art of Revision by Peter Ho Davies which are both useful as I finish my second novel manuscript.

Claire Baylis will appear at HamLit, the writers events at the Hamilton Arts Festival 22 – 23 February. Dice (Allen & Unwin, $37) is available to purchase online at Unity Books.