Christchurch writer Amy Head on the setting for her new novel – Rotoroa, an island near Waiheke, where the Salvation Army ran a rehab centre for alcoholics.

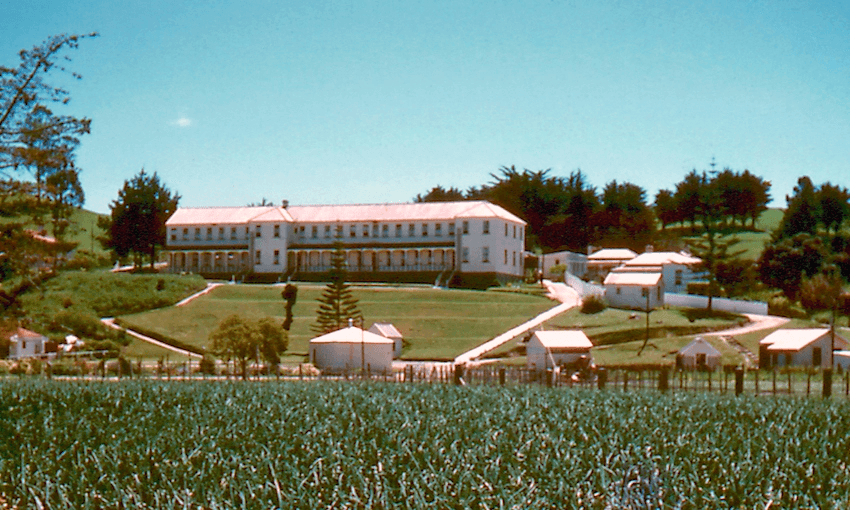

When I first learned about Rotoroa, an island east of Waiheke where the Salvation Army ran a rehabilitation facility between 1911 and 2005 (known early on as an “Inebriate’s Retreat”), it seemed rich with potential for fiction. Newspaper articles of the early 20th century detailed some of the inmates’ more inventive escapades. It turned out the men who were committed to the island showed staggering resourcefulness over the decades. They rowed out to trade fish for beer. They found psychotropic plants. They distilled pretty much anything they happened to have to hand, including raisins, pumpkins, parsnips, even sugar and water. Newspaper headline: “Drunkenness at Rotoroa: how the dry was made wet: industry promptly suppressed”.

Even better, until the 1940s, women were sent to the island next door, Pakatoa. In several accounts of the early days, men who hankered after female company either rowed or attempted to swim from one island to the other. In keeping with the 1920s, my mental image was in black and white – a desperate man struggling through dark waters. They’d be two estranged lovers, perhaps. How fraught. These excursions to Pakatoa became such a problem that eventually the police made the trip from the mainland. When they got there, they dressed up in — well — dresses, and paraded around before the windows of the women’s facility to lure the Rotoroans out.

My 1920s drunk emerged from the swells of frustrated love and took on a slapstick attitude. The tone of the reporting seemed to egg me on. Newspaper headline: “Slept among flowers” – a man on temporary leave from the island was found asleep in a flowerbed in Albert Park with a bottle of whiskey. “It was not a bed of roses”, the magistrate was reported to have wisecracked. How harmless and cartoonish was this scene in my mind’s eye, how silky and springy his outdoor bed.

There were also the stock associations that accompanied Victorian institutions — places such as Seacliff in Otago, a Gothic behemoth attended by a grim history. Janet Frame’s portrayals brought Seacliff into a colourised 1950s, but didn’t do much for our opinions of institutional treatment. Starting out, I was well and truly siding with the rebels. How many prison films feature protagonists who actually deserve to be there? Aren’t they usually wronged and misunderstood?

Like those deluded men on Pakatoa, who had braved the waters to crouch, peering out through the leaves at what were actually burly cops in skirts, I’d been drawn in by anecdotes that dressed up a hard, hairy reality. The more I read, the more the stories contradicted each other. Some men busted a gut trying to escape and others did their disorderly best to get sent back. Yes, one of the founders of Alcoholics Anonymous was recorded in 1960 telling the tale of “The day he lost his pants”, but all this comedy was an attempt to offset what is a heavy psychological burden. During my research, I saw mothers who were terrified that their children would become drinkers. I heard someone who’d waited for months to be admitted to a treatment programme only to encounter people using drugs the first night they were admitted. There were stories of generosity, too. It wasn’t unusual for recovering alcoholics to open their homes up to others who needed help.

A lot changed in the almost 100 years that Rotoroa operated, and it was this change that held my interest. The Habitual Drunkards Act of 1906 became the Alcohol and Drug Addiction Act in the 1960s, which just last year was replaced by the Substance Addiction Act. “Inmates” became “patients”, then “clients”. Today, treatment has diversified to include both day and residential programmes. It tends to be more community-based, and aims to better acknowledge the individual. As before, patience and boundaries help. As before, it’s preferable if the people running the programmes have a good understanding of what people with addictions go through.

But it was the 1950s I kept coming back to, around the time when they first began holding AA meetings on Rotoroa. Men on the island, many of them veterans of the First and Second World Wars, now “hit rock bottom”, “worked the steps” and got “sick and tired of being sick and tired”. A new manager was appointed to the island, who was a recovering alcoholic himself. Not just Rotoroa, but the rest of the country and perhaps the world seemed to be emerging out of something and moving towards something else, though they didn’t yet know what.

The 1950s was the when of my novel, then, but I needed a who. I wanted a range of perspectives, but it wouldn’t be easy; there were different sets of implications for youth and age, women and men, religious beliefs. One of the female characters has a career? That’s another set again. Political scientist Robert Chapman was sympathetic to women in his essay “Fiction and the Social Pattern” in 1953. They were facing a more complicated family life, he said, which they must manage “without readily available help in family planning and guidance and allied matters, and without crèches, kindergartens and home aides, which the mother often does not know how to ask for even where they do exist.”

But he was a product of his times. He continued, “Meanwhile, the attitude which the New Zealand writer takes to his society, and which informs his work [my italics], will continue to be based on…” These instances, of giving with one hand and taking with the other, seemed like dead ends, but the tension gave my characters depth, ultimately.

One character was an actual person who I met time and time again in my research. She was a journalist who wrote articles about the island under the name Elsie K Morton for something like 50 years. What a perfect observer, I thought; she’s worldly, she witnesses the island’s evolution over a sustained period. But her perspective, too, is shaped by her time. Unlike the nudge-nudge coverage I’ve already mentioned, her stories about Rotoroa were full of praise and vigorously optimistic.

Another character, Lorna, is a teenager. As such, she’s impressionable — as likely to be influenced by religious groups as by rock and roll. Her experiences during the novel would be considered by society at large to be beyond her years, but in a time when people don’t talk about their “shameful” experiences, who’s to know how normal or abnormal she really is?

The last character, Jim, is one of the island’s alcoholics, which means no more or less than that he’s become trapped by his particular means of escape. After all, by itself addiction is nothing. Its best trick is convincing its host of its own authenticity. On the one hand, there’s what’s going on physically, in the chemical processes of the brain. How that translates into thoughts and emotions—what it feels like for the addicted person—is another thing altogether: like easing pain, like trying get back to an inner life that’s rich and noble, a process that puts a great deal of distance towards themselves and others. As James K Baxter put it, in a letter to a friend, “When the octopus had me down under a rock, its name looked to me like life rather than booze.”

Rotoroa by Amy Head (Victoria University Press, $30) is available at Unity Books.