Flash fiction writer Sandra Arnold on the time a hot air balloon ride went horribly wrong and could easily have gone a lot, lot worse.

In 1992 one of my former students announced that he’d passed his pilot’s license exam, and wanted to thank all the teachers for helping him learn English and adjust to his new life in New Zealand. His gift to us, he said, would be a ride in the hot air balloon he was now qualified to fly, owned by the company he was working for. Not many of us were keen, but we didn’t want to disappoint him.

Early one morning we watched him inflate the envelope. Balloons were one of the safest forms of transport, he said. We climbed into the basket. The balloon rose slowly into the dawn sky. We gasped at the beauty of the land below from this new perspective as the sun struck the hills with gold. I pushed away all thoughts of our vulnerability.

One predictable aspect of Canterbury weather is its unpredictability. A blast of wind blew us off course. Instead of gliding smoothly over the Plains the balloon sped toward the lake and the pilot said he would have to land. He pulled at the ropes to deflate the envelope. The partially collapsed balloon hit the earth with such force it rocketed high into the air before landing again and tipping over, throwing all the teachers on top of the pilot and pinning his arms.

Wind filled the envelope, turning the balloon into an express train that roared through paddocks and streams, straight towards the lake. One passenger was jammed upright in a corner. He was the only one of us who saw how close the lake was and he said later he thought he would be decapitated as the balloon ripped through barbed wire fences. He wondered if that would be better than drowning.

Incredibly, the balloon stopped before it reached the lake and we all staggered out, grey-faced. Three duck shooters clutching beer cans wandered over the tussock towards us. They said they thought they were hallucinating then when they realised they weren’t, they expected to find pieces of smashed bodies. The man who thought about decapitation had a broken shoulder, but the rest of us were merely battered and bruised, though one person wailed that she’d lost her hat.

Only one passenger was willing to try another balloon ride the following week. She assured us afterwards that it really had been like floating on a cloud.

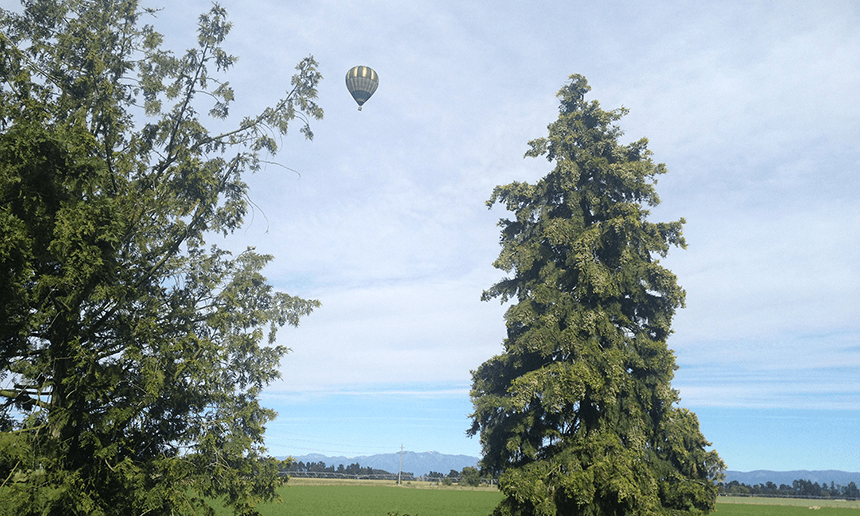

I remembered all this at the beginning of 2017 while watching a golden balloon floating over my house on the Canterbury Plains. It looked beautiful. Hands waved from the basket. I waved back. For the rest of the day a story began to coalesce. I wrote it down and titled it “The Golden Balloon”. The story – a flash fiction piece – is published in Fresh Ink, Cloud Ink’s new anthology of short prose and poetry.

I hadn’t heard of flash fiction until early in 2016 when I read that National Flash Fiction Day would take place in the UK and New Zealand in June that year. A poet friend defined flash fiction as similar to prose poetry with a narrative arc. He challenged me to try writing it, and recommended I read Flash Frontier, a New Zealand–based online journal edited by Michelle Elvy. Within its pages I discovered stories of 250 words which carried such meaning in their allusions that I was reminded of Hemingway’s iceberg theory that the most powerful writing lies below the surface. After this introduction I discovered a whole world of flash fiction journals and quickly became an enthusiast, both in the reading and writing of the form.

In the last decade there have been literary publications that include or focus exclusively on flash, as well as prizes, collections and anthologies. National Flash Fiction Day was established in the UK in 2012 as an annual event, each year producing an anthology of the best flash fiction. The first flash fiction festival was held in Bath, UK in June, 2017. In New Zealand, National Flash Fiction Day has been celebrated since 2012 with an international competition; a major anthology of flash fiction and prose poetry, Bonsai: The Big Book of Small Stories will be published by Canterbury University Press in 2018.

Supporters of flash fiction promote it as ideal for those who are too busy or attention-challenged to read longer works. Critics lament that it is the death of literature. Others dismiss it as a passing fad. But the best of it engages the senses with its beauty, new perspectives, surges of energy, and unexpected directions. A bit like a balloon ride.

Sandra Arnold’s flash fiction piece appears in Fresh Ink (Cloud Ink Press, $25), an anthology of new writing from contributors including James George, Siobhan Harvey, Nina Tapu, Thalia Henry and others. Cloud Ink Press was established by graduates of AUT’s Master of Creative Writing degree. Copies are available at Unity Books.