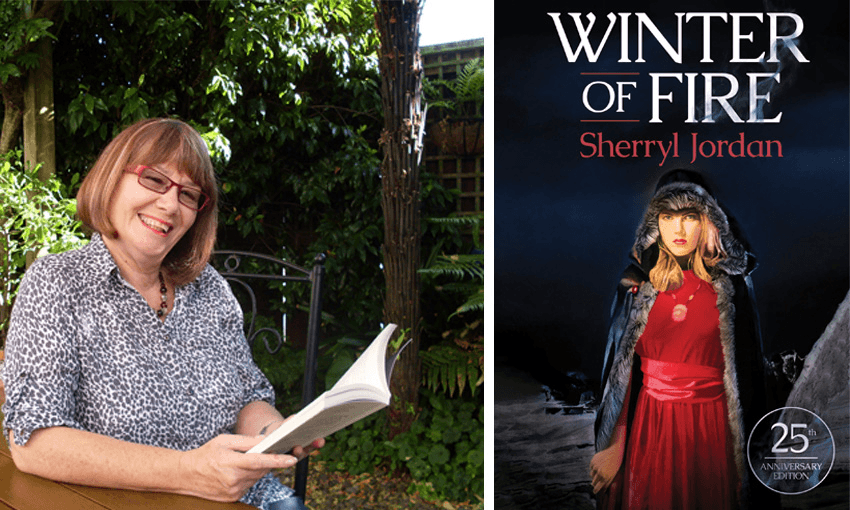

Beloved New Zealand fantasy author Sherryl Jordan died on 15 December 2023, aged 74. She leaves behind a formidable body of work – in particular her 1992 novel Winter of Fire.

Sherryl Jordan published over 30 books for children and young adults in her career. Many of those stories held in passionate esteem by a swath of millennial readers, and beyond, for whom Jordan’s rich world-building, striking characters and moreish romance offered immersive, intense and enriching new experiences.

Jordan was born in Hawera but lived most of her life in Tauranga. Her first published work was as an illustrator for Joy Cowley’s The Silent One in 1982. A few years later, in 1988, came Rocco (published simultaneously by Scholastic in NZ and the USA) the story of a teenage boy sent through time to a nuclear-ravaged landscape and society. After Rocco the novels flowed with hardly a pause: a cracking junior fiction series started with The Wednesday Wizard (1991); the spectacular YA masterpiece about witches, ESP and time travel The Juniper Game (1991); cult hit Winter of Fire (1992); Tanith (1994); moving historical fiction The Raging Quiet (1999); Secret Sacrament (1996). Many more titles were published through the 2000s including the latest, The King’s Nightingale in 2021.

The list of Jordan’s literary awards is long and includes: the USA School Library Journal Best of 1999; the 2001 Wirral Paperback of the Year for The Raging Quiet; the 2001 Buxtehuder Bulle Prize for Best Young Person’s Book of the Year for The Juniper Game; and in 2011, the New Zealand Post Children’s Book Awards Junior Fiction winner for Finnigan and the Pirates. In 2001 Jordan was awarded the Margaret Mahy Medal for her contribution to children’s literature, publishing and literacy.

The ultimate testament to Jordan’s gift as an author is the ardent quality of her fanbase. My copy of The Juniper Game is fiercely guarded. It’s an object I never lend and has been read (by me) at least a dozen times. It’s more than nostalgia: The Juniper Game is a bridge to my teenage self and the story is as fresh, and compelling and strange as it was then. That kind of literary magic is rare, but Sherryl Jordan wrote so many stories with this precious quality.

The following was first published in 2019 in celebration of the republication of Jordan’s novel A Winter of Fire. It’s a further glimpse into how much Jordan’s work means to readers, both old and new. / Claire Mabey

New Zealand writer Sherryl Jordan’s elated, transcendent novel for young adults, Winter of Fire, was first released in 1992. A quarter-century later, fans’ pestering paid off and it’s back in bookstores. This made former Spinoff books editor Catherine Woulfe very happy:

It’s hard not to sound like a nitwit when you’re writing about something you love completely. So please bear with me. Because Winter of Fire is my favourite book in the world and I choose to see its re-release as a sign that one thing, at least, is going OK in this mad age.

Winter of Fire is a story about inequality and intuition, about fire and hope and upheaval. It’s set in a winter world where one people, the Quelled, are branded and enslaved, confined to freezing tents and freezing coal mines. Another people, the Chosen, live in wooden houses – wood! In a land of no trees! – warmed by the coal the Quelled provide.

And then there’s Elsha, a Quelled woman who burns with an anger and conviction all her own. “Always at the heart of my life there has been fire,” she says, in the book’s opening sentence. (My other formative heroine, Tessa Duder’s Alex Archer, opens with similarly elemental self-reflection: “I have always known that in another life I was – or will be – a dolphin.”)

I still remember reading the next bit for the first time: Elsha is four years old, crouched in the dirt, singing to her scrawny cabbages, when a Chosen man approaches. He has a whip and he wears fancy furred boots. He doesn’t say a word because the Chosen believe Quelled have no speech. He laughs at the little girl. “Then he put his boot on my cabbages, ground them hard into the dirt, and turned to go.”

Oh it is on, raged 11-year-old me. I strode across that field and stood beside the little girl, the two of us snarling and spitting. And Elsha and I have been together ever since.

I love her for her lion heart, for her fire, but as I wrote for The Sapling last year, I love Winter of Fire for its peace and its strength. Because it makes my stupid brain shut up and be still for a moment. Reading it is like reading silence. Or solitude. And, always, joy. My copy is tattered and faded and 25 years old. But it hums with power, still.

Winter of Fire is special to Jordan, too – last year she told me Elsha and another character appeared to her in visions at a point that her hands were paralysed with RSI and she’d been told she’d never write again. Jordan’s stories often come to her like that, but Elsha was different, haunting her, plaguing her. “I can remember holding a pen and it was like trying to hold a brick, and I had great big sheets of paper and I just wrote, ‘Always at the heart of my life there has been fire’. And then I dropped the pen. And that was it for the day: great big letters, wobbly ones like a five-year-old.”

The book was released in 1992. Two years later the American Library Association picked it as its Best Book for Young Adults; that year it was also named Best Children’s Book of the Year by something called the Bank Street College of Education. It was short-listed in the good old AIM Book of the Year Awards. Nine years later it won Jordan the Margaret Mahy Medal.

The book’s editor at Scholastic NZ is Penny Scown and she is the reason Winter of Fire is being republished now. She’s been pushing for this for years, citing the book’s screeds of slightly manic reviews from dorkuses like me, and the emails she still gets from fans begging for a new copy.

“Never before have we received so many requests – from all over the world – to bring a book back into print,” Scown says in her triumphant press release.

As a kid I wanted to hug Winter of Fire to myself. Surely no-one else could love it like I did, therefore they didn’t deserve to read it. Twenty-five years and two kids later the obsessive-possessive thing has flipped: I would force a copy of this book – the best book in the world – onto every child if I could.

To that end, I’ve asked two fellow megafans to write about what Winter of Fire means to them.

Colin Roy teaches English and is the Head of Junior School at Fiordland College. It was an email he wrote to Penny Scown that prompted her to have one more tilt at convincing the acquisitions committee. “I have been using Winter of Fire for a number of years with Years 7 & 8,” Roy wrote, “and still believe it to be the most exemplary text of any I have used in all my years teaching. The problem is that I need some more copies. Are there any available?”

Told that there weren’t, sorry, he responded: “I still am obsessed with Winter of Fire as a student text for high schools… I would be ecstatic if Winter of Fire were to be reprinted. It is worthy.”

Here, Roy writes for us about the book he helped resurrect (abridged).

“This book is the best book I have ever read,” a student said to me, tears in her eyes as she finished Winter of Fire. I had not long finished the book myself, and wanted to see if it would be acceptable as a class text. The next two trial students responded with similar enthusiasm, and I immediately ordered 30 books as a class set.

That was 19 years ago. The books are now well worn – each year, my students read them repeatedly, looking for powerful scenes to analyse in their work. I have hunted for replacement copies as far afield as London. I have convinced librarians from other schools to give me their copies.

So I am thrilled that this treasure is being republished. It is the best news.

I came to teaching late. When Winter of Fire was first published, in 1992, I had left behind a working life which included operating bulldozers and heavy machinery, then a career change to welding and boat building, followed by work as a forestry contractor.

As a teacher, I see young people from a full range of backgrounds. At times I am rendered silent by some of the odds they face. Elsha draws the reader into a world where the only option is a life of hope. There is no justice in her world, only slavery, cruelty, beatings and depravity. She is indomitable and resilient, and finds a well-reasoned pathway against immeasurable odds. Yet she is easy to empathise with: Sherryl Jordan establishes such a closeness between the reader and the character that even if Elsha were to fail we would be left with a feeling that she has succeeded.

Elsha’s motivation is beyond herself. It is the self-sacrifice of a love-filled young woman against centuries of greed and a blind, powerful and ignorant class who live a life based on a lie. Jordan fills every page with the pathos of life in all its struggle and splendour, and the human spirit in all its depth.

It is these qualities which make the work a standout class text. Our young people are convinced they have a myriad of issues (and some of them do) so the power of Winter of Fire is that it introduces a true and realistic image of slavery and oppression. It provides perspective for the western privileged mind, and opens one’s eyes to the plight of people caught in the horror of slavery, past and present. Into the deepest, darkest, desolate hole of hopelessness, through the life of a young girl, the reader sees the power of a human spirit that will not be crushed.

Winter of Fire also examines another sort of slavery. Modern western society is filled with many people who are slaves to something. Many people are living their life, without living their life. Elsha’s perspective makes a reader face the reality of the type of relationships they have with others.

Winter of Fire is a novel which can bring about change and action and foster a vision for the future. It is a story for teenagers. It is a story for bulldozer drivers, welders, forestry contractors. It is a story for people who face oppressive odds, and even more, it is a story for the wealthy and those at ease.

Dr Susan Wardell lectures in social anthropology at the University of Otago. Her work exemplifies some of the main themes of Winter of Fire, touching on rites of passage, healing, faith, the representation of disability and the anthropology of evil.

When I was at primary school our library had three colour-coded shelves. The ‘red’ books on the top were for big kids. The chapter books. I was an avid reader and ridiculously excited to finally get to the year level where I could borrow books from the top shelf. Winter of Fire was the first book I picked. I can still see the cover vividly – a young woman in a red dress and a dark cloak, staring intently, unsmiling, off the page. “A dangerous world… a powerful woman”: the words hovered above a barren grey landscape. I don’t know why I reached for that book, over all others. But I made a good choice.

As a sheltered middle-class Pākehā kid I didn’t have much experience with danger, or power. Yet Elsha, the 16 year-old Quelled woman in the cloak, felt like kin. She was someone who dreamed, who felt things strongly and surely. And her world was so complete, so believable, dark though it was. It stoked my empathy and exploded my horizons.

This book made me passionate about social justice, long before I knew what that term meant. When I think about how and why I came to be a social anthropologist, Winter of Fire is a very real part of that story. My field seeks to understand and appreciate human differences, and to unpack how societies are structured, how beliefs and values and stories and identities shape human cultures, human social systems, and human practices – the beautiful and the terrible.

The story of the Quelled showed me how individual suffering could be connected to wider inequalities – and how an individual’s empathetic, caring heart could also be channeled into actions for larger scale change. I went through high school as a goody-good and a people pleaser. I probably still am, in too many ways. But Elsha’s rebellious streak was contagious. When she rises her people rise with her.

Winter of Fire gave me the understanding that sometimes you just need to tear down a rotten system. That you have to be brave when it matters. It showed me that heroics were not about force, but changing perceptions, changing laws, telling truths. (Elsha, firebrand that she is, recognises this too: “I cannot overnight alter this discrimination,” she explains. “It is ingrained in centuries of Chosen thought.”)

But it wasn’t a sanitised book either. I remember being horrified by this battle scene:

It was all confusion at first, men and horses locked in terrible conflict, the clash of steel on steel, and everywhere the sound of horses in panic, the yells of desperate men, and the screams when steel struck flesh…

It was so, so ugly. I had never read anything like it at the time – being fed largely on Enid Blyton and L.M Montgomery til that point! I was a romantic-minded child, and I remember thinking that scene almost marred the book. But today I can deeply appreciate that there was no glorification of violence there. It was sad and messy.

A lot of my interest in social justice over the years has also been tied into my Christian faith. I don’t know if I recognised it directly, the first time I read Winter of Fire, but over the years I’ve deeply appreciated the little elements of biblical symbolism in the story. The tearing of the temple curtain is the prime example. It resonates within a Christian worldview in a powerful way (Matthew 27:51), even though it is totally free-standing in the plot of the story – making sense to someone outside of that worldview, too, with nothing lost in the transition.

Plus when I think of it now, the radicalness of having a female protagonist who leads the way, who tears this curtain, is a wonderful counterbalance to the deep sexism still active in many facets of the church. Indeed, gender inequality is addressed directly again and again within the book in an extremely progressive way, as a central theme.

Today, as a lecturer at the University of Otago, I research, and teach, on a lot of social issues that relate to the book. Inequality and class, genocide and violence, religion, stigma, difference and disability. None of my academic work on these subjects has ever changed the esteem I have for Winter of Fire. In fact, I just see more and more incredible nuance in how the tale was told.

Along with gender, the book’s handling of both physical and intellectual disability lines up amazingly with social models of disability that I teach.

The social model (as opposed to a medical model) suggests that the experience of being ‘disabled’ is not primarily about the particular impairments of a person’s body, but is created by the barriers placed by a society built for the able. Only a story can communicate these nuanced social ideas in such a potent, accessible way, to a small child.

“It suddenly struck me that I had never seen a Quelled who couldn’t work…”

The book presents at first a dystopian view, where the Quelled hold only productive value, as workers, and any physical disability makes them utterly valueless, unworthy even to live. Then within this, a pocket utopia – a secret place where people with various injuries, such as amputations, demonstrate both their humanity and their capability, as a successful independent community. In addition, Shimer, a man who (by description) has Down Syndrome, is not only a valued companion, but completes many of the household care tasks, albeit in his own slower way, and is also prophetic.

I’ve probably re-read Winter of Fire at least a dozen times over the years – and I am NOT typically a re-reader. I buy a copy whenever I see it in a secondhand store. I pass it on to others. I’m especially known for trying to foist it on young teens in my community. Because I believe – I really believe – that it can light a spark of something bigger than the story itself. My daughter is five now, and I can’t wait to read it to her. I see Elsha in her, just as I see Elsha in myself, and me in my daughter.

It is so interesting, and thrilling, to consider the book being republished now. I think it is timeless, that it will have lost none of its intensity or relevance over 25 years. I suspect yet another copy will make it to my bookshelf, too. I have no doubt that it will appeal to today’s young people, who if anything have embraced fantasy and dystopian genres much more widely than was common 25 years ago. And the world doesn’t change either. They will recognise inequality, and empathy, and hope, just as I did.

When I think of the book, despite its dark plotline, I recall most of all the intense and intimate pleasures I found in reading it, every time. There were moments of such joy, against the backdrop of a very harsh world. Jordan is so good at writing the small, warm pleasures of human life, of friendship and food and song.

In fact that is a statement in itself, and now that I research and teach dark and fraught topics as my daily norm (i.e. death, grief, evil, religion and the supernatural, cultural politics, mental illness, terrorism…) I observe the same thing. That is, human resilience and agency. The way people care, and love, and live, amidst the worst situations. In fact, wherever I have travelled, this has struck me. Children playing pop songs on keyboards in the middle of refugee camps in Palestine. Women with babies tied to their backs, parading towards vaccination clinics in post-conflict South Sudan, in the most beautiful clothes and carrying colourful umbrellas. Ugandan mothers who warmly shared meals with me in their tiny dust-floored kitchens.

Winter of Fire may be classified as fantasy/dystopia, but the world that Sherryl Jordan wrote is the same one I find, wherever I travel, whatever I study. Both the depth of inequality, cruelty, and stubbornness in many societies (not excluding ours), and also the kindness, the courage, the possibility. I’ve met the Quelled, and the Chosen, and I’ve met many Elshas, fierce and soft and strong. I look forward to meeting the next ones too, as they pick up a shiny new copy from their own ‘red’ shelf. Maybe in a few years I’ll see them in my classroom, ready to deconstruct their own worlds. Ready to be brave.