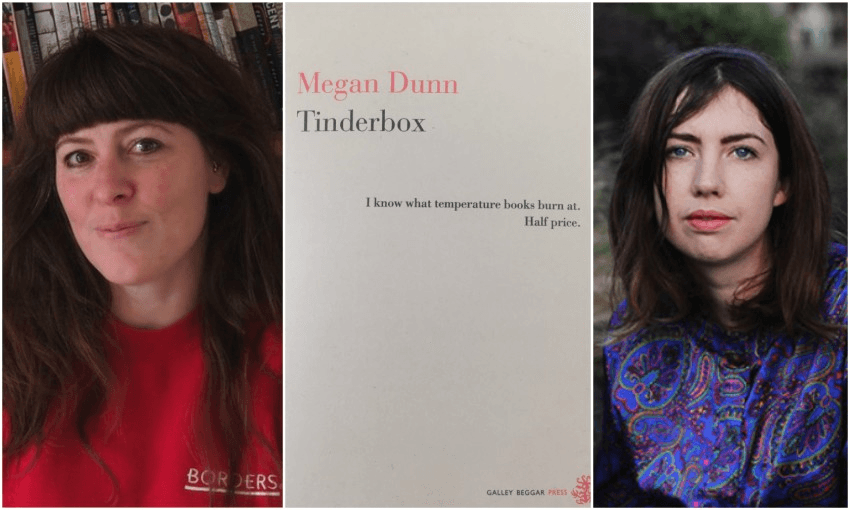

Poet Hera Lindsay Bird talks to Megan Dunn, author of a brilliantly funny new memoir about working at a failed bookstore while experiencing a failed marriage and making a failed attempt to write a novel.

I first met Megan Dunn the year after I had graduated from a writing programme and had to emerge back into reality and start paying off the huge student loan I had accumulated while trying to turn all my bad feelings into art. It was a very boring time in my life. I stamped hundreds of book tokens in the 13th floor of a skyscraper, and learned how to re-order paperclips and photocopy toner refills. That was where I met Megan, who sat across the hallway from me. I liked her and therefore barely spoke to her, because I usually wanted other people to leave me alone, especially people I liked and respected. I stamped book exchange tokens all year in silence and allowed my brain to slowly atrophy.

I knew Megan was a writer, and first read her work a couple years later when someone linked me to a few of her essays at Pantograph Punch about the New Zealand art scene. I loved them instantly. She had a dry, ironic sense of humour, an idiosyncratic writing style and an obsession with everything tacky and camp. She was also one of the first art writers I read who didn’t sound like they’d been hit squarely in the back of the head with the critical theory stick. Her writing was smart but never pretentious and it managed to be conversational, but never in the banal hyper-realistic “how are Sharon and the kids” New Zealand short story competition kind of way.

She has recently published a brilliantly funny memoir called Tinderbox with UK’s Galley Beggar Press. It’s about her attempt to rewrite Ray Bradbury’s classic sci-fi novel Farenheit 451 from the perspective of Bradbury’s female characters, and includes excerpts from her original drafts. It’s also about the collapse of a marriage, copyright struggles and what it’s like to work as a bookseller in a collapsing, corporate bookstore chain. It’s dry and pessimistic, and totally compulsive reading – I had to stop folding down pages when I came to a good line or passage, because her book was starting to look like an origami project undertaken by a moron. It’s already one of my favourite New Zealand books.

*

In your book you talk about Eleanor Catton saying she would never write a book about herself, and your embarrassment at finding yourself doing so. What are the pitfalls of autobiographical writing? What was it like for you to write about your life this way?

I think Catton said in an early interview she would never write a book about someone writing a book. This is a point of view I’ve heard before. The argument is circular and sounds simple when boiled down and paraphrased by me. But broadly there is a tension between fiction (which scales the dizzy heights of the imagination) and non-fiction (which is laid out before us like a set plate and all one has to do is describe it, right?) However, the relationship between the two is far more entangled. And I think most writers speak to that complexity, including Catton. I just read that particular interview at a low ebb.

I first fell in love with the novel and I wanted to be a novelist, so I crush hard on fiction writers. Autobiographical writing does have a lower place in the canon and maybe that’s because it sits somewhere just above (or below?) Oprah Winfrey and Jeremy Kyle and countless TV shows that are fuelled by ‘real life’ drama (although fiction does this too). I grew up watching Oprah with Mum and we both hazarded our guesses at the mysteries of human behaviour. There’s a strong connection between autobiography and women’s writing too of course (the personal as political, the idea of art as therapy), which Jeanette Winterson spearheaded best in her line, “I have noticed that when women writers put themselves into their fiction, it’s called autobiography. When men do it, such as Paul Auster or Milan Kundera it’s called meta-fiction.”

What was it like reading back over the draft of your original rewrite of Farenheit 451 to select excerpts for Tinderbox? Were you tempted to keep putting more in? You’ve written both the novel, and the memoir of writing the novel – what were the two processes like?

There are certain conceits to Tinderbox – one is that it is true. I wrote about 20,000 words from the perspective of Bradbury’s female characters Clarisse and Mildred but it was such a farce! So camp! And the story kept derailing. I was meant to be interested in the blonde teenager Clarrise who transforms Bradbury’s fireman, Guy Montag, with her love of reading but instead I gave her a slutty best friend called Clementine who kept goading Clarisse to to screw Montag. Then there was a really stupid scene where Clarisse finds out she dies in Bradbury’s novel and gets into a fight with her mum, wailing, “Why didn’t you tell me?”

So I gave up and wrote a 30,000 word novella called Miles and Mabel about a 19-year-old blonde vixen and a 39-year-old fey man working in a failing bookshop. That was also quite farcical.

When I came back through this nutty draft to select material for Tinderbox I was no longer putting pressure on the writing to be ‘a work of serious literature’, and that helped quite a lot. I could now see it for what it was: silly.

And I am a writer hugely energised by silliness.

I loved your descriptions of working at Borders, which contained some of the funniest sections of the book. Do you think working in a bookshop changed your relationship to writing?

Yes, I always felt I knew too much. There’s a certain type of self-published author who would come into Borders and be shocked to find one copy of their book alphabetised by surname and shelved in the appropriate section, spine out. I always wondered what they expected. A spot lit cameo in front of store? Loud speaker announcements? As Borders progressed – or regressed – we did have to pimp deals over the in-store tannoy.

This probably led to me devising a concept for a new MTV show, Pimp my Book, like the popular Pimp my Ride. It would star the US rapper Xzibit who would turn up on the porch of self-published authors, but instead of helping to pimp their beat-up car, he would pimp their book. The book would then be bedazzled with spray painted flames, fake fur, gold chains, small subwoofer speakers and TVs or maybe even iPods or tablets could be added to the front cover, especially if it was a hardback. Mega-bling!

Tinderbox explores the dynamic between, inverted commas, high & low culture. I know you love Sweet Valley High and in one section of the book, defend Mildred’s obsession with reality TV. But at the same time, you write about your frustrations with having to sell thousands of copies of Dan Brown and Jodi Picoult. Do you think the distinction between high and low is totally useless, or just individual?

The conceit of merging high and low of course isn’t new, but it still gives me great joy to do so. Some of the distinctions between the two are defined by audience. Isn’t that why romance is traditionally such a maligned field? Some of it is to do with expectations of different genres. Imagine judging The English Patient by the standards of Anchorman? Or vice versa. I love David Sedaris’ comment, “The opposite of funny isn’t serious. It’s not funny.”

When I did Harry Rickett’s creative non-fiction course at IML a few years ago, he said, “you can write from a place of mixed feelings.” That freedom was something I embraced in Tinderbox.

I turned Bradbury’s villian the mechanical hound into an obsolete piece of merchandise, because I believe technology isn’t a wholly destructive force. It’s important to note I have never read Picoult or Brown and my frustration about selling them is just about honestly portraying a certain prejudice towards popularity. To me, Mildred was trivialised in Bradbury’s original and held in contempt and mass popular culture is often trivialised and dismissed, and sometimes we do this at our own peril. Look at Trump.

I too work in a bookshop, and books about books are often very sanctimonious & reverential. Your book is so funny! What is your relationship to books about books?

Books about books seem to be a Marmite proposition, but more people are into Marmite. I loved Nicholson Baker’s The Anthologist about Paul Chowder, a middle aged manic pixie dream man (like manic pixie girls but older and more prevalent in literature) stalling on writing his anthology of poetry. It features all sorts of crazy riffs on the pleasures of rhyming and is just a total cosmic delight. I also loved The Clothing of Books by Jhumpa Lahiri, it was so wonderful to a read a writer really analyse what their book covers convey and promote. I highly recommend it. Also, Deborah Levy’s Things I Don’t Want to Know, a response to George Orwell’s Why I Write. The things that make Levy write are also the things that make me write, ie the things I don’t want to know.

In terms of fiction one can’t look past Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Bookshop, which is slender but perfectly formed and contains a funny passage about selling Lolita in a smalltown.

There is one scene in the book where, as a child, you show your father some Little Matchgirl-esque story, and he calls it melodramatic. Michele Roberts describes your book as “unsentimental.” But I know you also love campness and excess. How do you navigate the two?

I like to think I navigate the two like one of Beyonce’s backing dancers in the ‘Single Ladies’ video: thrusting and squatting when the choereography demands it, all the while showing great sass and pomp. Or perhaps like Beyonce herself in ‘Crazy in Love’, I’m always ticked by the moment when she is standing next to Jay Z and flicks her fur (real?) coat over his shoulder. I guess what I am saying is I think writing should be catchy and fun and addictive. Literature doesn’t have the monopoly on word play – everyone has language and I love the way pop culture stretches and snaps words. Language is mutable and that incurs loss but also amazing gains. Some of my favourite sentences are from pop songs. I love Gaga’s line from ‘Bad Romance’, “I don’t want to be friends.” So simple, yet so true. Sums up every relationship I had in my 20s. And her title ‘Bad Romance’ is the synopsis of hundreds of thousands of novels.

You used to be a video artist. What precipitated your shift to literature?

Money! I moved to London when I was 27 and had no cash whatsoever. Hard to believe but in 2001 you needed a bit of cash to have a decent computer and an edit suite. I started to write because I was miserable with no creative outlet. And I thought: hey, writing costs nothing. What a lie: writing costs everything. It will take nothing less than your whole life.

I know that you studied writing in England, and have an unpublished novel somewhere. How do you feel about that work now? Will it ever see the light of day?

I started my first novel The Santa Parade when I was at the University of East Anglia. At the end of the degree I had loads of agents after me, and it seemed like that novel would have a happy ending. But it didn’t.

The Santa Parade was about a prostitute working her last Christmas in an Auckland massage parlour and had fantasy sequences with the creepy Whitcoulls Santa, who comes to life and attends the parlour and is massaged by the girls, then has a heart attack and dies! I’ve heard different things about how to “fix” that novel, one publisher was kinda interested in taking it on, but wanted to set it in Shoreditch in London, presumably because he had been to Shoreditch. (But the creepy Whitcoulls Santa is on Queen Street.) That publisher also asked me to change the narrative voice from first person to third. I asked why, expecting an amazing formal answer, instead he said, “if it is in third person people won’t think it is autobiographical.”

Was it autobiographical? After Elam, I worked for nine months as a receptionist at Femme Fatale massage parlour and the novel commemorates some of what I saw there in 2000, just before prostitution was decrimalised in New Zealand. One of the working girls who was my friend at the time said, “Who wants to be taxed on fucking?” That’s not the party line on such matters, but her sentence went right through me.

The Santa Parade is uneven. I remain fond of the creepy Whitcoulls Santa against the odds.

You are better known in New Zealand for your art writing. What was it like trying to enter the literary scene here? Is the literary or art scene more hostile, or do you not give a shit?

It was hard. I came back to New Zealand in 2010 as general manager of Borders in Wellington and then that went bust. I was wondering what the hell to do for paid work. I was middle-aged (the horror!) and still hadn’t made it. It was a low point and I was over everything, including myself. I sent a few things out to the best literary magazines here and they were all rejected. I was bewildered. I had just done a great international MA, been fawned over by agents, and been writing seriously for years, my first freaking piece was published in Landfall yonks ago. Suddenly, it was game over. Had I really gotten so bad? I had a pre-existing relationship with NZ art and that world just opened up with very little effort from me. I am constantly asked to write about art and I enjoy it – art is so avant garde and endlessly weird.

However, some part of my imagination still has to go feral, to write about me and my mum and mermaids and the end of the world. And so I am. At the end of the day you either keep going or you don’t.

I really admire the NZ literary scene. There’s no shortage of talent here.

What are your favourite adaptations or retellings of literary works?

Hands down: the 1980s British TV series of Sue Townsend’s The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole aged 13 and 3/4s. That book and TV show are pitch perfect. I love Adrian Mole (who also wanted to be a writer. His biggest problem: he was an intellectual but at the same time not very clever.) It is quite a political book in some ways, really captures working class Britain and Adrian’s Mum (played by Julie Walters) who longs for her own identity beyond motherhood. I also loved the theme song to the series which was called ‘Profoundly in Love with Pandora’ and performed by Ian Dury. I encourage everyone to listen to it on YouTube and marvel in its brilliance.

If you could force one contemporary author to rework one classic work of fiction, what would you like to see?

Will Self do [Jane Claypool Miner’s] Senior Dreams Can Come True – an 80s romance about a fat chick who runs round the fields all summer, then is thin enough to realise her dream of becoming a cheerleader. I read it one night on a childhood sleepover and couldn’t put it down. The cover featured a pretty girl holding her pom-poms triumphantly over her head like fireworks. Do you think Will could ‘work it’, Hera?

I hear you are currently researching mermaids. How is that going? What is it for?

I have been interviewing professional mermaids on Skype for my next book. I was writing a novel about a mermaid in a contemporary setting but it kept nagging me…what next? So I surfed the internet and noticed all the real professional mermaids out there…and their tails! Did you know the bottom of a mermaid’s tail is called the fluke? I didn’t till I started this research.

I was one of the little girls who loved Daryl Hannah in Splash (1984) and throughout my life I have often produced art about mermaids. In 2009 I published a short story called ‘The Mermaid at the Playboy Mansion’ and recently I Skyped one of the first professional mermaids, Linden Wolbert, and found out she once attended a children’s charity at the Playboy Mansion and performed in the ‘famous’ grotto as a mermaid. (It really wasn’t her scene and she was uncomfortable.)

Mermaids are quite an intellectual taboo – something the professionals often experience too. In the mid 90s I pitched an article celebrating Hannah as the mermaid Madison in Splash to the sub-editor at Pavement and she just looked at me drily and went, “you’re the only person I know who has been influenced by Daryl Hannah.”

So my mermaid book is all about the fact that HEAPS of people all over the world have been influenced by Daryl Hannah in Splash SO THERE.

Tinderbox by Megan Dunn is available at Unity Books.