A reissue of an earlier piece in honour and remembrance of Nigel Cox, who passed away ten years ago today.

Alongside David Slack, who always has a cackle on his lips, I appeared as guest speaker at a session on satirical writing at the Auckland Writers and Readers Festival in May, and it’s possible that I came across as bored, hostile, and baffled, but only at the beginning and the end.

It was chaired by Stephen Stratford. The session was 60 minutes. His introduction, which featured a history of satire, seemed to go on for about 50 minutes. I thought: God almighty, when will this end? And then: will it end? End it did, eventually, and he skillfully chaired a fun session. He thanked us, the audience clapped, and began to make their way to the exit when a woman suddenly rushed onstage with a microphone and asked everyone to please sit down again.

It was former Metro books editor Susanna Andrew. She talked very fast. She was saying something about my writing, I didn’t catch everything, but got the idea that she was saying nice things. But why say them onstage? What the devil was going on? Afterwards, she said I wore a furious expression, and that she felt afraid. I wasn’t angry. I was bewildered. Susanna announced I’d won an award and then presented me with an envelope. Everyone clapped, and made their way to the exit.

It was explained to me later that I’d won the inaugural Nigel Cox Unity Books Award in recognition of my writing; the prize was $1000 worth of books from Unity. Well, for heaven’s sake.

I kind of gloated over the award for several weeks before heading into Unity to start spending the prize money. By that time I’d decided on the first book. It felt important to choose wisely. I bought Phone Home Berlin (Victoria University Press, $35) by Nigel Cox.

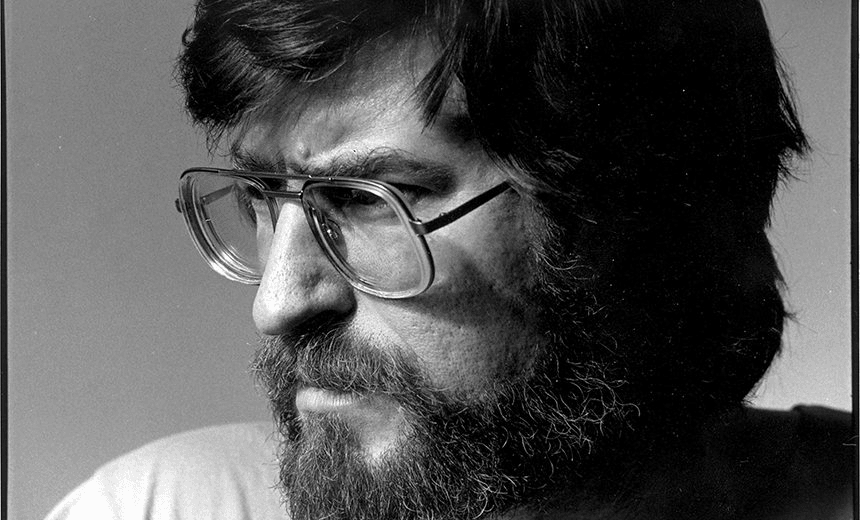

He was a big, rangy guy. He wore glasses and had dark hair. He was married to Susanna Andrew and they had three children. He wrote clever and difficult novels which I made no attempt to read. We met when he was a bookseller at Unity in Wellington in the 1980s. He turned the shop into a kind of literary salon; everyone was always talking about books, arguing about books, enthusing about books. He was the centre of it, and he always had a smile on his face. He was a happy guy.

When Ian Wedde’s clever and difficult novel Symmes Hole came out in 1986, with its various Wellington settings, Nigel said to me: “Ian owns this city, in a literary way.” I thought that was just about the most fantastic thing anyone could say of a writer. It was so admiring, and also so generous. It didn’t make me want to try and read Symmes Hole – I know my limitations as a reader – but it warmed me to Nigel. I really liked him and wished I’d got to know him better. He died in 2006. He was 55.

In 2002, when I worked as deputy editor at The Listener, I accepted an essay by Nigel about Germany hosting the World Cup. He’d moved to Berlin to take up a senior position at the Jewish Museum. I can’t remember whether he offered the story or if I commissioned it, but I remember how much I liked the piece. It’s included in Phone Home Berlin, a posthumous collection of his non-fiction. Strange to read it now. It’s the luck of every editor who receives a terrific piece of writing to usually be the first person to read it; the story brought back that time, and the pleasure I took in his writing, and its insights: “Is it too much to suggest that every German since the Holocaust feels they were humiliated before they were born? Living among these people, that is what you sense, painful knowledge of original sin.”

Sad, too, to read it now. What a loss to New Zealand writing. The voice is very engaging – intelligent, self-effacing, observant. There’s another quality, which Damien Wilkins correctly identifies during their 53-page conversation in Phone Home Berlin – wisdom. He was a wise man.

I read the book slowly because I wanted to savour the wisdom, the voice, the joy of reading someone so at ease with prose. There are essays about the exhilarating trash he read as a kid growing up in Masterton, about life in Berlin, about returning to New Zealand, about a novelist’s challenges. Much of it’s memoir. There’s a small moment in one particular memoir about his OE in England which I absolutely love. It’s just a sentence explaining that he ran into a guy called Brent, a friend from Wellington, at Heathrow.

“He met me at Heathrow – ‘Cox, ya idiot’ – and persuaded me to go down to Kent with him for a few days.”

It’s the thing that Brent says. Cox, ya idiot. It’s the fact that Cox remembered it after 30 years – just a small, throwaway line, a classic New Zealand greeting between two mates. Maybe he made it up, I thought it sounded like something Brent might have said. It’s also the decision to place it within hyphens in the middle of the sentence. Parentheses would have ruined it; it needs the hyphens to give it a certain pace, to give it comic timing. It’s the “ya”. It’s the charm of the whole little three-word hyphenated arrangement, made possible by an ear for speech and a quick wit. All writers make decisions, one after another, in their writing. Cox, ya idiot. The inclusion of that is such a quick, good decision, and it tells you that you’re in the presence of someone who’s going to make a lot of other really good decisions, someone who can really write.

The Spinoff Review of Books is brought to you by Unity Books.