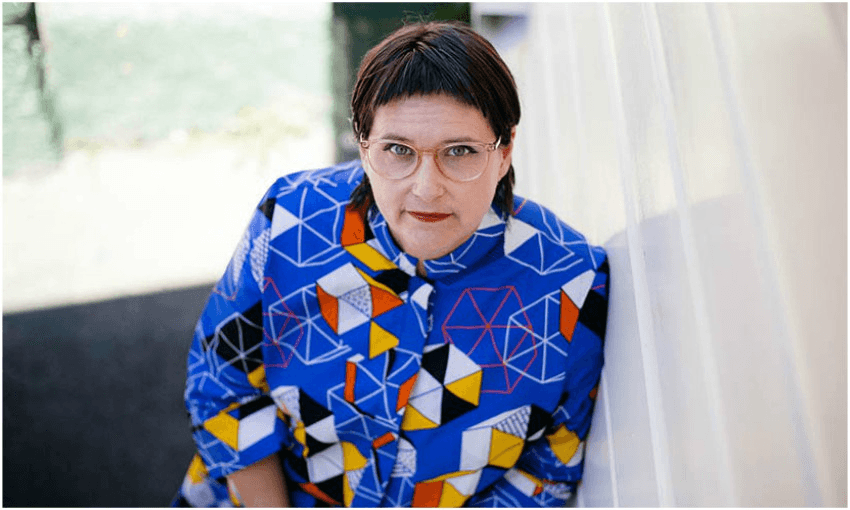

Neatly sidestepping spoilers, Briar Lawry of Little Unity reviews Pip Adam’s new and widely lauded novel, Nothing to See.

“How do you even review a Pip Adam book?” a colleague asked. “She’s too nice!”

“She is,” I agreed, “but luckily her books are always brilliant.”

In all honesty, I said this having barely started Nothing to See, but that didn’t dampen my confidence at all. It feels like the written word equivalent of going to a fringe festival show or esoteric movie from a creator you believe in: it might not be a pleasant experience, it might be weird, or grim, or painful – but it will be interesting. And that’s so much more fun than something that is just regular old tick-the-box good.

Adam’s books always manage to scrub away at corners of my brain that have never seen light, and turning back to the real world after marking the page and closing the book feels uncertain and new. Going into your first Pip Adam book is arresting – but it prepares you for future journeys in reading her work. You know to keep your mind open and receptive and let the story flow through you rather than try to stop and cleverly pick apart where you think things are going – because reader, you will invariably be wrong.

The shape of the story is summarised on the blurb. “It’s 1994. … It’s 2006. … It’s 2018.” Really, it tells you the whole story, as far as the key plot beats go. But it’s the in between that matters, how those beats are reached, making sense of the who and the why and the how. “[Peggy and Greta] live with Heidi and Dell, who are also like them.” Like them how?

“One day, Peggy and Greta turn around and there’s only one of them.” One of who?

I’m predominantly a children’s bookseller. I’m used to giving parents and grandparents and other would-be gift-givers a quick précis of a book, often spoiler-laden (“yes, I see that things look dire in the spread you opened to, but I promise that the jellyfish is going to be OK!”). When I put on my more generalist book person hat, that option is often less viable – and it’s definitely the case with Adam’s work.

When asked what it was about, what I thought of it, in the context of what kind of customers it might suit, I paused, and thought about it before answering – and have continued to think about it since. If you didn’t like The New Animals, you probably won’t like this either. It’s probably not something you’re going to buy on a whim from an airport shop before a long-haul flight – use your imagination to think about when that was still a thing – if you went in looking to see if there’s a new James Patterson. And it’s not one that you’re going to give to a 70-something woman for her book club if the last book she read was Before the Coffee Gets Cold. But for readers willing to lay their trust in the author to take them on an unpredictable and yet remarkably quotidian journey through three decades? This is going to be your jam.

Like the books that came before it, Nothing to See is compelling – but not a quick read. I would be sceptical (but impressed) if anyone could read this book in one sitting. To me, it can be taken in great gulps, each one deeply satisfying with a hint of constant unease. Happiness is not something that comes easily to the women of this book, with loneliness of various kinds: Margaret, who we officially meet in the 2006 section, exists in ongoing loneliness. It seems heightened at night, whether it’s the loneliness inherent sitting in a bar watching other people enjoy their booze while clutching your own glass of Coke, or that of lying in bed with a space where her other half should be.

The prose in Nothing to See is clear and arresting. I would never describe it as lyrical, and yet there’s a poetry to it in the same way that the best contemporary poets are shaking things up:

“They were so close to sleep, drifting in and out. Everyone thought they wanted to drink but sometimes they wondered if what they really wanted was just to be alone again. Maybe they didn’t want to work in the shop anymore, and then they were asleep. Gone. In a dark unconsciousness where time travelled weirdly or not at all. Where they dreamed they were a butterfly – not realising they were asleep until they woke up the next morning.”

Adam is an author who manages to lull you into thinking she’s playing by the literary rules while making her own playbook. The way she plays with phrasing reduplication and repetition is simultaneously utterly natural and technically masterful in the way it echoes the big plot goings on.

As time passes, and the story builds more into an era of web moderation and app-based surveillance, more and more technical computing language is woven through. It adds a depth in two quite contrasting ways, lending both increased authenticity to the way the tech stuff is handled and fantasy in the way that some of the language could seem quite opaque to less tech-savvy readers. Some of the core mysteries of the book start to really build in the final section (what happened to Dell? where did the tamagotchi phone come from? how did any of this happen anyway?), so using extra jargon to help build a bit of a literary smokescreen works beautifully.

When I read The New Animals, I felt like part of why I was so drawn to the story was the familiarity of the locations. The K Road cafes. Flats in GI. That late night walk through Ōrākei to the Waitematā. I saw a Tāmaki I knew. Nothing to See pointedly doesn’t refer to locations – and its fantasy and surrealism kicks in at a much earlier juncture – but at the same time it felt no less real. That crisp writing, that willingness to tell a version of the world seen through eyes that the world doesn’t like acknowledging… it’s a combination that transports.

So how do you even review a Pip Adam book? Effusively.

It’s not for everyone – but the most interesting books never are. If you do think it sounds like a bit of you – mystery, technology, surrealism, sex, questions of identity and reality, anyone? – then you are in for an absolute treat. Settle in with your non-alcoholic beverage of choice and make sure you’ve got your tom yum or carrot sandwiches on stand-by. But hold the quiche.

(Read an extract about that quiche here.)

Nothing To See, by Pip Adam (Victoria University Press, $30) is available from Unity Books Wellington and Auckland.