The old utopian ideal of an unmoderated free speech arena can’t survive this upswing in right wing violence, writes the co-author of a report calling for greater regulation of the internet.

Like many people my age, I feel like I grew up both on and with the internet. There was an amazing sense of freedom in the early days of chat rooms and message boards in the 90s. A friend doing a project on Ethiopia messaged directly (as far as we knew!) with a government minister there. I learned about Japanese anime, which I still love. It was an exciting time because it felt like a new world where everyone was equal, and you could talk to anyone. It is hard to describe if you were not part of it, but if you were, you know exactly what I mean. I remember feeling like my mind was blown because I had just been talking with a real live person from Singapore. This would have been about 1998. Ever since that time I have felt a strong cultural affinity for the utopian ideal of the internet to which many in the technology industry subscribe. Many people I know in senior roles now I probably first met in a chatroom somewhere back when we were teens.

But we find ourselves in a very different world, as I was reminded with the recent telco decisions to block 8chan. Meanwhile, it appeared that the only action the government regulator was able to take against a forum which has hosted the announcement of three massacres was to issue an approving press release.

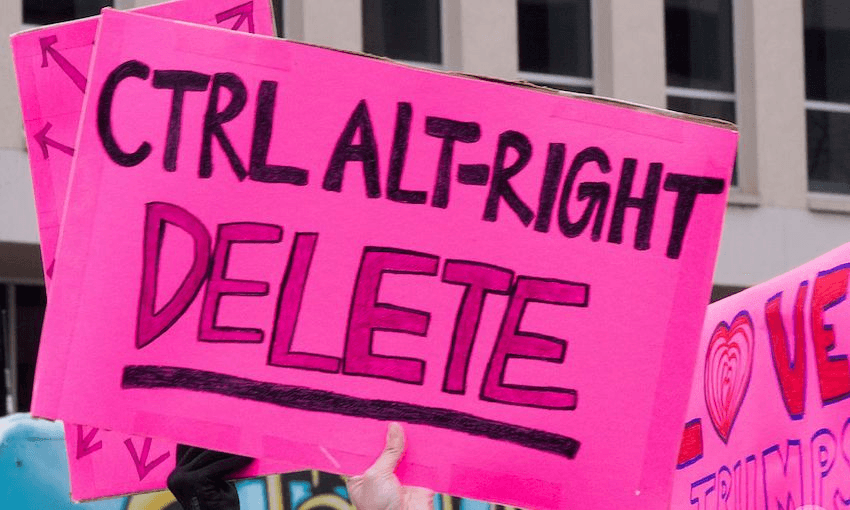

Unmoderated message boards, once a fascinating and exciting new community, are now being used in sinister ways to radicalise a generation. Like perhaps many other women online, I first began to understand this with the so-called ‘Gamergate’ affair back in 2014. Vicious and manifestly misogynist attacks were organised on message boards, then unleashed on public-facing platforms like Twitter and Facebook. These tactics had been trialled on message boards like 4chan for years.

Technology companies took no responsibility for what was going on, even as targets were faced with terrifying events like ‘swatting’. Male acquaintances seemed not to get it to a frightening degree. I remember being told that Zoe Quinn (the catalyst for gamergate) was probably ‘not a very good girlfriend’. It was like hearing someone complain that the in-flight meals were bad during a plane crash. Who could possibly care? These guys were not in fact interested in ‘ethics in gaming journalism’, they were looking for an outlet for rage and entitlement. And they had become highly and effectively organised.

Gamergate was the poison tree whose fruit was 8chan. And even the free speech purist who founded 8chan now wants it shut down.

And so I have found myself on the side calling for greater regulation of the internet, an idea that remains heresy for parts of the tech community.

Specifically, I co-authored with Claire Mason a report for the Helen Clark Foundation in May arguing that we need a social media regulator along the lines of the BSA, where decisions about what content is blocked, removed and regulated can be made. During a subsequent appearance on Q&A we pointed out that these decisions are made anyway, but at the moment they are made by private companies, with little or no public oversight. Who made the call at Spark to pull the plug on 8chan? Despite researching this topic and following it closely, I have no idea where the final decision rested inside the company. I agree with their decision but do not think they should have had to make it alone. It is an unreasonable burden to put on business.

Our current legislative framework has avoided taking responsibility for these kinds of hard decisions about acceptable content. There are at least five agencies with some coverage of social media, but none have a mandate to address the platforms. It is a regulatory patchwork with holes cut in it.

There is room to improve existing legislation, such as the Films, Video and Publication Classification Act 1993 and the Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015, to increase the liability of social media companies and impose higher financial penalties for non-compliance.

But considering the size and influence of social media companies, and the clear commercial incentive to encourage borderline content in order to drive engagement, we recommend that the New Zealand government takes a comprehensive regulatory response. A legislated duty of care overseen by an independent regulator would be a good place to start. (For more please read our full report!)