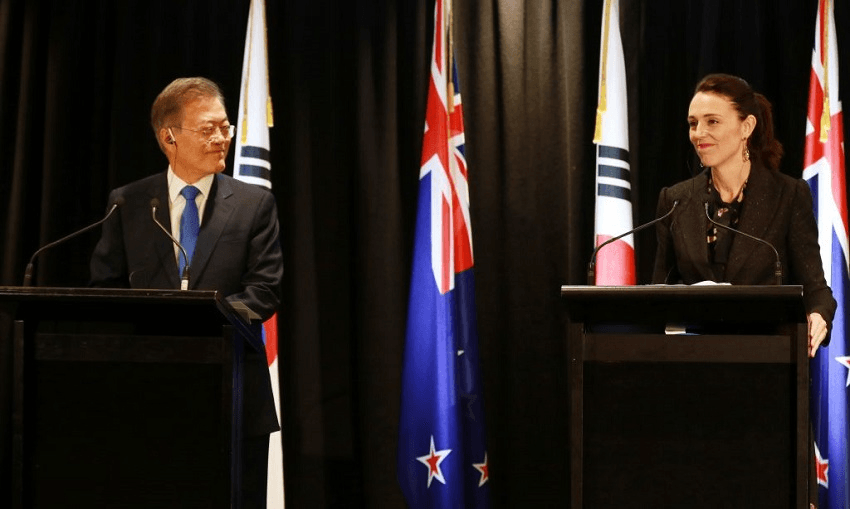

South Korean President Moon Jae-In this week completed a successful visit to New Zealand. Rebekah Jaung explains where New Zealand-Korean relations are today and what we can do to help restore lasting peace on the peninsula.

If you took a walk through Auckland Domain on Monday morning, you may have noticed some commotion outside the museum. Over 200 members of the local Korean community gathered outside the building, hoping to catch a glimpse of South Korean President Moon Jae-In and his wife Kim Jung-Sook, and celebrate their visit to Aotearoa. They were waving flags – South Korean and New Zealand ones as might be expected, but also a white flag featuring a blue, undivided Korean Peninsula.

This flag featured in international news this year when it was carried together by North and South Korean Olympians at the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics. For the last 20 years, it’s been a symbol of the aspiration for peace on the Korean peninsula. For those 200-plus local Koreans on a miserably wet Monday morning, waving the unification flag was the best way for them to directly express their excitement and support for President Moon and his administration’s work towards lasting peace on the Korean peninsula.

A lot has happened since the year’s first inter-Korean summit on April 27. The number of times the leaders of the two Koreas have met throughout history has more than doubled (from two to five). Truncated roads and railway lines are being reconnected, gifts of produce are being exchanged and cultural exchanges are becoming the norm. We’re starting to get a taste of what normalised relations between the two governments might look like. As an avid follower of news from the motherland, I’ve spent days watching live streams of the family reunifications in August and had my head in my hands with every sign of backtracking or instability in the peace talks.

Although great strides have been made in terms of improving inter-Korean relations, history has demonstrated that this relationship can be heartbreakingly fragile in the context of global affairs. One recent heart sink moment was the controversial New York Times article which reported the existence of “newly discovered 16 hidden missile bases”, which indicated “a great deception” by North Korea. This take has now been criticised for misrepresenting information that was sourced from a think-tank with close ties to the military-industrial complex, and for mirroring the type of sensationalist reporting which supported the eventual invasion of Iraq by the US in 2003.

In Korea, this approach was criticised in an open letter to the Times by the editor of one of South Korea’s progressive newspapers. “While reading the Times’ coverage, I sometimes feel that US national interest takes preference over peace on the Korean Peninsula and that the success of North Korea-US talks is treated as less important than concerns that their success might strengthen Trump’s position and buoy his spirits.”

So where do we stand here in Aotearoa? And what more can we do to make peace a real possibility? The relationship between the two countries was forged by New Zealand’s participation in the Korean War and has largely been maintained since then through revisiting and building on these ties. Local and visiting Korean officials, as well as community groups, often hold events which pay tribute to New Zealand veterans, and there are a number of government-funded scholarships for the descendants of veterans with some veterans continuing to support charities in Korea.

Even someone like me, with complex feelings about the war and militarism, can appreciate the strength of feeling behind that bond. When I was a medical student on a busy surgical attachment, I had a patient ask about my ethnicity then break down into tears when I told him I was Korean — turns out he was a veteran. I know it was a vicious, bloody and traumatic war, and the bond of having participated in it is exactly why we have a responsibility and first-hand interest in ensuring that it finally ends.

Perhaps with that connection, along with an international reputation for peace (flawed though it is) and relative freedom from the lobbying of the military-industrial-complex and burn-it-all-to-the-ground political battling of the US, New Zealand is ideally placed to be a friend to the Korean people once again. To share a bit of relentless positivity for the work that the two Koreas are doing, to support the reestablishment of humanitarian aid to the North (which is still the best chance we have of improving the lives of average citizens) and supporting a more nuanced and diplomatic way forward than towing the American line of denuclearisation as the start of the conversation. An opportunity to be an ally in the peace process instead of war.

On Wednesday 5 December, the day after President Moon returned to Korea, Kim Soon-Ok, a survivor of Japanese military sexual slavery passed away at the age of 97. She was taken from her family in Pyeongyang when she was 20 and was never able to return to her hometown. This is just one of thousands of stories of families separated throughout Korea’s history, one marked by colonisation and division for multiple generations of Koreans on both sides of the demilitarised zone. Although achieving lasting peace and eventual unification will be significant regardless of when it happens, for the rapidly dwindling number of survivors of Korea’s tumultuous past, time is running out for political and global leaders to figure out a way which would finally allow them to return home.