On Saturday, Tara Ward was one of 35,000 southerners who marched against the government’s proposed cuts to the new hospital.

My bus from the Ōtepoti Dunedin hill suburbs into the city usually only has a few people on it, but on Saturday morning, it stopped for passengers at every single stop. The Otago Regional Council had made buses free between 10am and 3pm, and as we drove along Highgate and wound down through Dunedin’s hills, more and more people got on. Most were retirees who wore warm hats and carried homemade protest signs under their arms. “I know where you’re going,” one grey-haired woman said to a stranger who sat next to her, their knitted heads quickly bowing together in conversation.

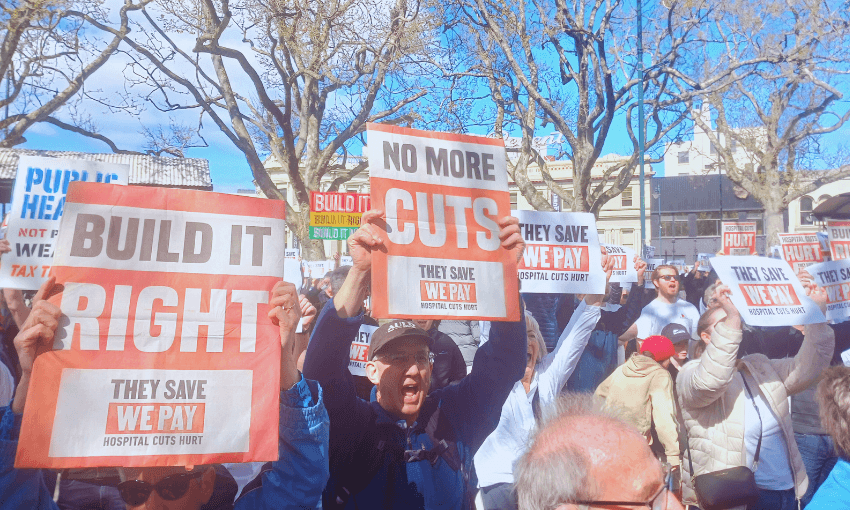

Saturday was a blue sky day, a true Dunner stunner, clear and warm in the sun. By the time we left the full bus in the central city, George Street was packed with people – students, families with young kids, weary middle-aged people like my husband and me – all walking in one direction. Everyone was headed north towards the dental school, many wearing white “you save, we pay” campaign T-shirts, and everyone was talking about one thing: the government’s U-turn on the new Dunedin hospital.

In July 2023, National campaigned in Dunedin on restoring funding to build the new hospital if it was elected. “Trust us,” Christopher Luxon promised, more than once, to the people of the south. Last week, minister of infrastructure Chris Bishop and minister of health Shane Reti arrived in town to announce that due to budget blowouts, the planned hospital redevelopment would either need to be reduced or done in stages. They are proposing two scaled-back options, but those critical of the decision say the proposed $3 billion cost is “a smokescreen” and that any reduction in services will result in lives being lost.

Southerners are generally stoic, non-demonstrative folk, but this news pissed a lot of people off. So many, in fact, that when we turned right into Frederick Street just before 12pm, we were met by a sea of people. They filled the end of Great King Street next to the dental school and spilled across the road next to the current hospital, which for many years experts have said cannot be retrofitted. We stood under a row of kōwhai trees, their yellow blossoms offering shade from the sun, as a young boy in a blue sweatshirt quietly held a “You lied again” sign.

“Don’t be sick, National,” read another sign, while “National puts the ‘N’ into cuts” was written neatly on a white bed sheet. Nearby, a protester held a beautiful orange cat wearing a white knitted top. “I knew someone would bring their cat,” someone said.

At 12pm, members from the nurses’ union and city councillors weaved through the crowd to begin the march to the Octagon. As we began the slow walk along George Street, past Yaks n Yetis and Slick Willy’s, even people who weren’t marching were protesting. Retailers stood outside their shops and others sat on benches, all holding up those “they save, we pay” posters. I saw a nurse friend with her elderly mother outside the Meridian Mall, waving and cheering the marchers on. Outside Farmers, someone’s grandparents stood together in the sun and clapped. Unusually for a protest march, nobody on the street looked away.

“Build it once, build it right,” we chanted, over and over again. Next to me, a woman’s phone rang, but she couldn’t talk long – she was on the march. After several peaceful minutes, we saw the front of the march make the small rise up the hill to the Octagon, the nurses’ union’s purple flags snapping in the breeze. “First the ferries, now our health, National hates the south,” two impassioned marchers yelled. An elderly woman on crutches kept her own pace. “I’m going to need new hips when I get there,” she joked.

At the Octagon, someone wearing a giant hoiho costume stood next to the Robbie Burns statue and a voice over the loudhailer announced that there were still protesters waiting to start the march at the dental school, 850 metres away. The wind blew the sound of their chants towards us as a team of doctors in scrubs wheeled a hospital bed onto the lawn and performed CPR on a dummy. I felt sad and angry and proud, all at the same time.

“This is the biggest crowd we’ve seen in the Octagon since Danyan Loader came through in 92,” the protest MC told the crowd. The speeches began with Dunedin mayor Jules Radich, and in every one that followed, the message was clear: this isn’t just Dunedin’s hospital. This hospital serves the largest geographical region of any New Zealand health board, covering Rakiura Stewart Island, Invercargill, Gore, Queenstown, Central Otago, Maniototo and the Waitaki. It’s also a teaching hospital connected to the medical school at the University of Otago, a vital tool in training and research for clinicians and medical professionals.

Those who spoke were impassioned and angry. Registered nurse Linda Smillie argued that the government’s decision was a deliberate choice; there is money to build new hospitals, but the coalition chooses to spend it on things like roads and tax relief for landlords. Others spoke about meticulously planning this hospital since 2007, where even the smallest cut in services means the hospital will no longer meet the needs of the south. Piri Tohu-Hapati from the Māori Medical Students Association called it “dire myopic short-sightedness” and said “to stall or cut corners is to be complicit in preventable deaths and long-term suffering”.

Former chair of the hospital advisory group (and ex-Labour minister of health) Pete Hodgson pointed out that the last pile for the new hospital was capped on Wednesday, one day before the government announcement. “The government wants the rest of New Zealand to think you’re being selfish by wanting a proper hospital,” former city councillor Richard Thomson told the crowd, while former ED doctor John Chambers put it simply: “This is about privatisation. This is exhausting.” Clutha district mayor Bryan Cadogan was particularly irate. “If you keep the original tower block, it won’t be long before it’s covered under the Historic Places covenant. What could go wrong?”

Near the end of the speeches, the Otago rescue helicopter flew low across the Octagon, and 35,000 heads – one quarter of Dunedin’s population – lifted skywards together. It was an unexpected, powerful reminder of everything that’s at stake, and the crowd burst into spontaneous applause. “Inadequate clinical facilities will result in patient deaths,” Smillie said moments earlier. “When that happens, I want it today to be very clear on whose shoulders the responsibility for those deaths rest on.” The clapping ended, and the crowd, now determined and united, sang an adapted version of the classic 90s Highlanders rugby banger.

“Build our hospital,” we sang. “Your pre-election claim should not be a house of pain.”