Books editor Claire Mabey attempts to untangle the age-old problem of good art made by bad people.

Not a year goes by that news of the heinous deeds of a beloved artist doesn’t come to very public light. So far this year writers Neil Gaiman and Alice Munro (cw: please take care with those stories which involve abuse and assault) have made the news, and for many fans it will mark the severance of a relationship with their art. But should it?

You’ve been squirming on this conundrum for ages. Since you found out that most of the dudes involved in the art history and literary canon land that you studied are somewhere on the spectrum of prickish behaviour. In light of this latest, horrible, news about revered short story writer, Alice Munro, where have you landed? Can you divorce the art from the artist?

Obviously, you can, sometimes. Roland Barthes figured this out for us way back in 1967 when he wrote ‘The death of the author’ which says that the text has got nothing to do with the author but with the reader. His argument is that you can take that Picasso cubism and claim it because it’s your own imagination that makes meaning of it, not old mate misogynist.

Sorry but that is clearly badly aged bollocks. The Munro allegations are incredibly serious and frankly monstrous. Surely you’re not going to rush out and read her stories now: that would be indulging the work of someone who did an unconscionable thing? And there are so many books to read in this world, why would you choose to support someone like that?

The thing with Munro is that I’ve hardly read any of her work and so in this case I can happily say I won’t be bothering to catch myself up. I don’t feel the need to separate the art from the artist because I’ve come from the artist first, if you know what I mean?

Not really, no. Please enlighten?

Because I don’t have a strong connection with Munro’s work I don’t feel any need to defend or protect her art from her. If I went to Munro now, knowing what I know, I’d find it very hard to appreciate those stories on their own terms because I’d be looking at them through the lens of “how could she have done what she did?” And “I feel guilty for perpetuating this idea of the art idol when we know she’s actually an art monster”. So it’s different to say, Anne of Green Gables books which I read and loved without giving a fig who the writer was. I have a relationship with that art first and foremost.

And what if you found out that LM Montgomery who wrote Anne of Green Gables was a cretin?

Honestly? In that case I’d have to apply Barthes because those books have already fused themselves into my brain. They’re mine, not hers. So I think I could successfully make an internal case for continuing to love and own them, despite the subsequent knowledge of shitty personnel in the making of them. I’d protect my relationship with that art born from the period in which I didn’t know about the author: she was already dead to me.

Right, so you’re saying that it’s a matter of timing and order? If you know the art before you know about the artist, then it’s OK?

Kind of, yes. Unless … it’s really bad.

How bad?

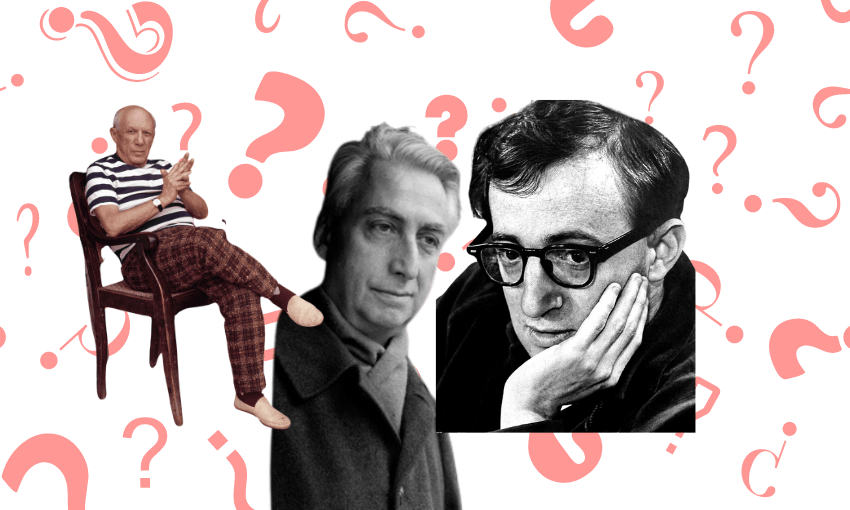

Two words. Michael Jackson. Bill Cosby. Harvey Weinstein. Roman Polanski. Woody Allen…

That’s a lot more than two words but I see what you were doing there. I know you’d still find it hard not to dance if Thriller came on, right? And you really liked that Woody Allen movie with Scarlett Johansson and Rebecca Hall and Penelope Cruz in it?

OK look, with MJ I would have to try and control my feet, but I would also find it excruciating and sad and I’d turn it off or moonwalk out of the venue. I did once love that artist but I was steeped in childhood innocence about who he was. As an informed adult I’d now never seek out his music. I can enjoy my innocent memories, but I wouldn’t want to expand on them.

With the Woody Allen movie, I saw that when I was only vaguely aware that he was controversial. So that movie I can enjoy through the lens of memory and ignorance. But of all the films I could go and watch now, that wouldn’t be one of them. If anything, the crimes of those artists helps eliminate option overwhelm.

You haven’t seen Annie Hall though and you want to, I know you do.

That’s because everyone says it’s wonderful! But I can live with a desire to see it and not prioritise it, can’t I?

You’re being incredibly inconsistent. Sounds to me like you’re a case-by-case operator. Also how do you deal with the idea that if you dig deep enough, probably every artist you love has done something shitty.

Case-by-case is the only fair way to be. You have to give every circumstance a thorough hearing before you cut yourself off from good art forever. Also sometimes there are allegations that aren’t proven: surely the whole innocence until proven guilty concept must still apply. And to your second point, it’s only logical that nobody is perfect but not everybody is as terrible like the artists you named above: those ones were/are art monsters.

I see what you did there, you’re referring to Claire Dederer’s book, Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma. Are you referring to the notion of the privileged audience, then? That only the privileged can afford to go Barthes and kill the author?

Well actually yes. Pretty much. Have we swapped sides? I think a lot of these men, in particular, existed in the canon for so long because the patriarchy allowed them to get away with grotesque behaviour towards women. Instead of being admonished they were heroised. I have zero interest in perpetuating that adoration. In fact, Gaiman can probably take a hike because there are literally about 100 books in my tbr pile and I have no time for him. And while I have fond memories of reading Harry Potter in my youth, I will never purchase another book by she-who-shall-not-be-named because I am extremely disappointed in her obvious lack of many things, like humanity.

Aha! So you, Mabey, are in fact incapable of divorcing the art from the artist. Case dismissed.

No, not quite. I think if you have a strong, existing relationship with the art (pre-knowledge of bad behaviour) to the extent that you’ve poured so much of your own self into that work and made lifelong meaning and memory from it, then I do think the balance of power lies with the reader/viewer/listening. But if that artist is known to you as a cretin and then you seek out their work and pay for it, that’s a whole other matter. I also think there’s a calculation that could be argued around what the art of the monster contributed versus what the monster themselves committed. For example the writer you cannot deny that you love, Virginia Woolf, had some appalling ideas. But it is possible to condemn those aspects of her portfolio and see how progressive other aspects of her art were, for their time.

Ah OK, so you’re also advocating for engaging with the work but only critically? That’s why you don’t like Hemingway, right? You didn’t really know about him at all but when you read those books you saw misogyny in the texts.

I’ll never bother much with Hemingway because I don’t like the art. It annoyed me. The words were good and the writing strong but the ideas aggravating. Anyway that’s a sideways step in this argument. Sometimes when the artist is a salty old dog you can see salt and dogs in their work and you can comfortably conclude that their worldview is not for you. That’s a healthy way to consume. With historic texts/art there’s a distance that somehow softens the approach: you can contextualise the work into its time and read critically accordingly.

It’s important to apply a critical lens to most art (except maybe … no actually can’t think of anything exempt from that) but there is a difference in the nature of that critical lens between contemporary artists and historic ones. It’s much harder, for me, to apply critical distance to contemporary artists who are making from within the same world as we are reading / absorbing them in. It’s harder to separate art from artist when they’re right under our nose and affecting people in real-time.

Still case-by-case then.

Yep, sorry. Mabey by name, maybe by nature.