Instead of more roads, what about more rail? James Dann draws up a plan on how he’d improve Christchurch with a brand new transport system centred on heavy and light rail.

Christchurch is a sprawling mess. Its only major geographical feature is the Port Hills, a buffer that has slowed growth in one direction. From the vantage of these hills, you can look out across the Canterbury Plains, once the nation’s breadbasket, but now increasingly covered by metastasising exurbs. Though Greater Christchurch is forecast to continue growing at almost twice the rate of Wellington, our growth strategy seems to be entirely dependent on cars and roads. But as both Auckland and Wellington are finding, cars and roads just don’t cut it. Especially with the looming crisis of climate change, why doesn’t the South Island’s biggest city have a plan that anticipates these challenges?

There are many reasons why we need a better transport network. We need to get people in and out of town, to the places they work, play, and live. We also need to build more houses, and a good transport network can open up areas for new developments. We need to invigorate the CBD, which has everything except people. Most importantly though, we need to prepare Christchurch for the effects of climate change. We know that we need to make massive changes to the way we live to have any chance of stopping climate change (you can argue that New Zealand is too small to even bother, to which I say: why bother doing anything?). Mass transit is a far more economical way of moving people around. On top of that, any new rail scheme could utilise electricity, which the South Island is quite good at generating from hydropower so we’d be reducing our carbon footprint. But on top of that, a well-designed transit network will encourage greater density in the centre of Christchurch, making not only travel by rail, but also by foot/bike/electric scooter a much more attractive prospect.

Christchurch needs to promote density within three to five kilometres of the CBD. To do this, we should look at a light rail network that is deliberately designed to build density. By this, I mean that it isn’t designed to connect everyone in the city. Christchurch is already too sprawling to make that an economic reality. We should instead look to connect a series of dense urban areas which aren’t too far from the city.

We should also be aiming to convert brownfield sites to residential. There are light industrial areas, especially in the south and east of the CBD – Addington, Sydenham, Waltham, the CBD between Barbados and Fitzgerald, and the south of town between St Asaph St and Moorehouse Ave – that could support tens of thousands of people in well-designed apartment buildings. These people could then walk to their nearest stop and ride into town, and if they didn’t work in town, quickly transfer to another line that would take them to their place of work. This sort of growth not only makes the city a more vibrant place to live, but also works towards a more sustainable form of urbanism.

Brendan Harre has written and researched an excellent article about Christchurch’s transport challenges on his blog. He outlines the growth patterns and demands of Greater Christchurch, and highlights what he calls the “fat banana”: an urban development corridor that stretches from Rangiora in the north, curving down through Christchurch and out to Rolleston in the west. I don’t disagree with his analysis, but I think that we need to avoid the “fat banana” at all costs, rather than enabling it to develop further.

One of the issues with simply activating the rail corridors to the satellite towns in the west and the north is that it actually makes it easier to live there. Sure, it will reduce the emissions of anyone who regularly commutes, but it doesn’t do anything to arrest sprawl. We need to limit the growth of these satellites, and the paving over of some of the best market gardening and farmland in the country. If we can limit the sprawl of these satellites to their current footprint, then we will not only reduce our carbon emissions but also increase our food security. Another side-effect of limiting sprawl is that we will retain more open farmland, which is going to be needed to absorb water when it floods. The development in the south-west especially is going to make one-in-a-hundred-year floods much more frequent, unless we can better mitigate the water run-off.

There are further issues with the satellite towns, mainly around governance and rating. I could go on about how Selwyn and Waimakariri don’t pay for the infrastructure costs that their ratepayers have on Christchurch City Council, but we all just want to get on to pictures of train maps, right?

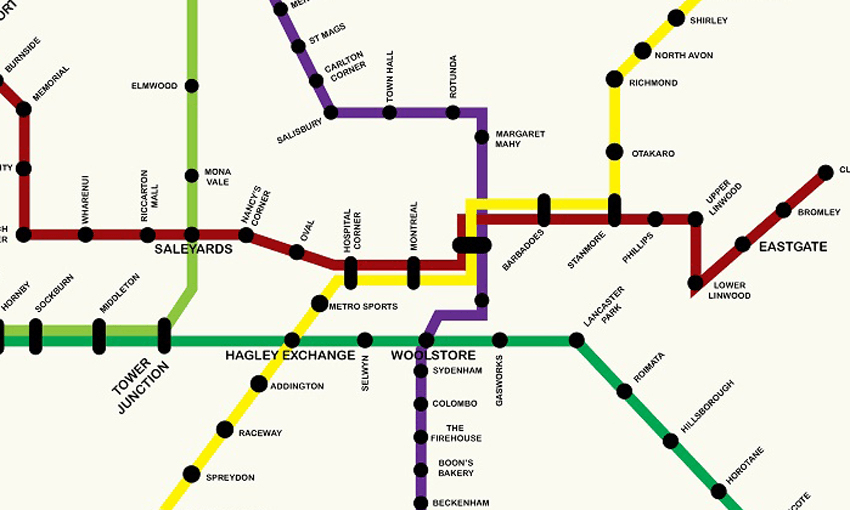

The model that I’m proposing puts passengers back on the existing heavy rail corridor and adds in light rail to provide greater network coverage. The rail corridor in the city comes in from the south-west through Rolleston and Hornby, before getting to the station at Tower Junction. Here, there’s a small station where the only passenger trains currently in service, the Tranz-Alpine and the Coastal Pacific, leave from. It’s around here that the rail splits, with the northern line heading through Papanui and Belfast on its way to Kaikoura and Picton. The eastern line rides along the southern fringe of the city before turning south-east and heading to the port of Lyttelton through the rail tunnel. To help clear the rail lines, another heavy rail line would need to be built that would effectively connect Rolleston and Belfast, allowing north-south freight to largely bypass the city.

The main issue with the existing heavy rail network is that it doesn’t connect to the city. The old Railway Station was on Moorehouse Ave, between Gasson and Manchester Streets, and was the home of a cinema and Science Alive before the quakes. Now it’s been demolished and is, ironically, a car yard and petrol station. While it might be nice to put a station back here, it was never close enough to the CBD. Christchurch used to have an extensive tram network up until the ’50s, and these tram lines have led to the development of many of the inner suburbs of the city. In researching for this piece, I found some of the maps of the old routes and was stunned to discover that I’d mapped out routes that were, in some cases, identical to the historic ones. I swear I didn’t know what the routes were.

Around 1950, Christchurch had 16 tram lines and a population of just 170,000. The city has more than twice that now with Greater Christchurch projected to have around 750,000 by mid-century. The city can definitely support a light rail network. Sure, fewer people had private cars at that point, but surely we’re heading towards a future when fewer private cars is a necessity.

The light rail routes that I’m putting forward would connect the heavy rail network to the city, unlocking the full potential of this corridor. It connects Christchurch to the satellite towns to the north and west using the existing rail corridor. It also connects both the airport and the port to the CBD. However, the main focus is to connect and strengthen the urban fabric within a five-kilometre radius of the square. To do this, I’m proposing three light-rail routes that will complement the heavy rail corridor. Through this, you will be able to get to and from libraries, swimming pools, sports grounds, entertainment venues, Christchurch’s two tertiary institutions, and all of the major shopping malls (as well as all the amenities built or being built in the CBD). These routes will enhance the amenity value of the neighbourhoods adjacent to them, as well as providing an incentive for more intense development in key areas. It also provides excellent coverage in the south and eastern city fringe, a potential development area that I’ve previously highlighted.

The Purple Line is the most North-South of the routes, running on a similar route to the current Blue Line bus. The north end would be at Papanui in the area between the existing rail corridor and Northlands Mall. As well as the mall, which has two supermarkets and a cinema, this area also boasts a high school, a swimming pool, a library and a large number of other shops and services. The Papanui Exchange would serve as a transfer point for people coming in from the north of the city via the Green Line who would switch from heavy to light rail for the remainder of their journey into the CBD.

The route would run from the Exchange along Papanui Road, connecting to schools (including St Andrew’s, Selwyn House, and St Margaret’s), St George’s Hospital, Merivale Mall, and then Carlton Corner. After crossing Bealey Ave into Victoria St, it would roll past the casino before turning into Kilmore St and the Town Hall, then into Manchester St, with a stop at the Margaret Mahy Playground that would also serve the Theatre Royal and Turanga. The main exchange, co-located with the Bus Exchange, would put people right into the heart of the CBD, or allow them to transfer to either of the other services.

If they continued on the Purple Line, it would take them over the railway and into Sydenham, with an exchange at Woolstores for the Green Line to Lyttelton or Rolleston. From Woolstores it would ride down Colombo St, with stops at Sydenham, Colombo, the Firehouse, Boon’s Bakery (where Countdown is now), Beckenham Shops, Waimea (South Library), before finally terminating at the bottom of Cashmere Hill.

The Maroon Line takes its colour from the University of Canterbury, which is a key part of this route. As previously outlined, I’ve designed a compact network, with the idea of promoting a more dense urban core for the city. However, this route is the one exception as it connects the airport to the city – a strategic advantage for both residents and visitors alike. From the airport, the route would take Memorial Ave towards the city – a wide road that could easily handle a double-track rail corridor, as well as providing a scenic backdrop for visitors coming to our city for the first time. The tram would then turn south with two or possibly three stops near the university. It would then continue to Church Corner, and from there, along Riccarton Road. The Saleyards station would allow people to transfer to the Green Line, before the route continued along Riccarton Ave through Hagley Park, with a stop at Hagley Oval, and another at Hospital Corner.

The Maroon Line would then meet up with the Yellow Line, as both head east through the CBD with a stop at Montreal St close to the Arts Centre, Art Gallery and the Council. After the exchange, the Maroon Line would continue heading east with the Yellow Line until they separate at Stanmore Road with the Maroon Line heading towards Phillipstown, Linwood College, Eastgate Mall and finally, Cuthbert’s Green.

The Yellow Line would start in the North East at the Palms Shopping centre. It would wind its way south and west through Shirley into Richmond, then south down Stanmore Road until meeting the Maroon Line, as was previously mentioned. It would trace the same route west until reaching Hospital Corner where it would veer south-west, stopping at the Metro Sports centre, which would also service Hagley High School and the Canterbury Netball Courts. After crossing Moorehouse Ave, there’d be an exchange with the Green Line. The Yellow Line would then continue in a South West direction along Lincoln Road through Addington. A stop at Raceway would serve not just the raceway, but also the Arena and Stadium which are part of the complex. Following another station at Spreydon, the Yellow Line would terminate near Hillmorton Hospital. Though the hospital has been overlooked for some years, a direct connection to the main hospital might make the CDHB rethink its facilities. There’s also a reasonable amount of land here, which could accommodate a park-and-ride scheme for people coming into the city from Halswell, Aidanfield, Wigram and Tai Tapu.

The two Green Lines use the existing rail corridors. Green Line North starts in Rangiora, travelling through Kaiapoi, Belfast, Northwood and Redwood, before meeting the Purple Line at Papanui Exchange. For those who didn’t transfer, it would continue heading south with stops at Blighs Rd, Elmwood and Mona Vale, before meeting the Maroon Line at Saleyards. It then meets the other Green Line at Tower Junction. These Green Lines would have fewer stops, as they have much longer distances to travel before they get to Christchurch proper.

Green Line West starts in Rolleston with a stop at Templeton before it gets to the malignant mall-scape of Hornby which would need two, if not three stops. After another stop in Sockburn and one at Middleton, it would reach Tower Junction. If continuing on to the CBD, passengers would continue to either Hagley Exchange (Yellow Line) or Woolstores (Purple Line). The Green Line runs parallel to Moorehouse Ave and there’d be more stops along this section to service both nearby residents as well as employees who work at the many business parks in this stretch of the city fringe. It would be a quick walk from the Gasworks station to Ara. The line then heads south-east towards the tunnel, with stops at Lancaster Park (possibly a future residential development), Roimata (close to Ara’s Sullivan Ave campus), Opawa, Fauxpawa, Hillsborough (the Tannery), Horotane, and Heathcote Valley. The Green Line would then head through the tunnel to Lyttelton, where it would then be possible to take the ferry across to Diamond Harbour.

I’m aware that this network doesn’t cover everywhere. However, I think it does a pretty good job of using the existing rail corridor, plus three new lines. The largest areas within the five-kilometre radius of the Square that wouldn’t be covered are currently between the Papanui and Palms termini, including Mairehau, Edgeware and St Albans; Woolston and Bromley between Cuthbert’s Green and Hillsborough; Waltham and St Martins; and Somerfield (where I live!), Spreydon and Barrington.

There are obviously areas that this doesn’t cover at all. I’ve outlined why that is, though I appreciate that people will disagree with it, especially if they happen to live there. While connecting out to Sumner would make for a beautiful trip, I doubt that there is the density to justify it. Plus, most people would still have to get up a hill from wherever the train stopped, so I suspect they’d probably still continue to drive. New Brighton is perhaps more problematic. The area has been repeatedly overlooked since the quakes and even well before them. Many of the residents seem to think that the council and the government have ignored them and, if this scheme went ahead, no doubt that they’d continue to think that. Aside from the five-kilometre density rationale, there are a number of other things counting against the east. Obviously, it was badly hit by the quakes and most of the demolished houses were in this area. Unfortunately, this means that the region will never recover the population density that it had before, and would need to justify mass transit. Additionally, the houses were demolished because the land was bad and that’s still the case. It might not be the best place to be building heavy infrastructure. Finally, we need to prepare for climate change by thinking 10, 20, 100 years ahead. If we do nothing to reduce the rate of climate change (which sadly seems to be the most likely outcome) then low-lying areas will be increasingly affected by it. It doesn’t make sense to build infrastructure for 50 years when it might be underwater in 15.

As well as connecting to strategic areas like the port and airport, this network also links to Christchurch’s mall. I don’t like malls. I hate them. I hate being in them, I hate having to try and park at or near them, and I hate the excesses of capitalism that they represent. But I know that I’m in the minority. Christchurch is a mall city. Forget ‘Which school did you go to?’. ‘Which mall did you go to?’ should be the cliched first question from a Cantabrian’s mouth. Before the quakes, retail in the CBD was being hollowed out by the malls. But since 2011, they’ve only got bigger. While they’re all ludicrous, the two areas that have exploded the most are Northlands/Papanui, and Hornby/The Hub. I don’t think it’s any coincidence that these are both the closest malls to the satellite towns to the north and to the west.

Anyway, the malls are here to stay. People use them and we need to service the people who use them. This plan links all of the major malls (Northlands, The Palms, Eastgate, Riccarton, and Hornby) as well as many of the secondary ones (Bush Inn, Fendalton, Merivale, The Colombo, and The Tannery). Northlands is a good example of how this could work. The mall has two supermarkets, a couple of major chain stores, and a cinema. There are also some council services (a swimming pool and a library) as well as a few government ones (a school and an office building with a number of government services). It’s a great place to put a train and tram station. Malls also have heaps and heaps of carparks. With a bit of planning and negotiating with the property owners, it might be possible to start using the car parking at malls for park-and-ride schemes. While the malls might not want to give up car parking spaces, I think the increase in patronage from the transit system would more than make up for it.

Whenever the case is made for light rail in Christchurch, the Sensible Men In Suits Who Know About Money pop their heads up to tut-tut and tell us we can’t afford it. To which I’d respond: where were you when the government threw $500m at a convention centre with no business case? Or $500m at a stadium that’s forecast to lose money? Maybe your phone just wasn’t working each and every time the previous government announced giant motorways, spending more than $900m on a bold plan to move gridlock from the northern motorway to Cranford St.

This isn’t a costed plan. It’s not meant to be. It’s about starting a discussion about Christchurch’s transport future. Canberra is about to open a 12km long light rail line which cost $700m AUD, so that’s probably a decent ballpark figure for each line. We’d get far more bang for our buck in Christchurch than we would in Wellington or Auckland – our wide streets and flat terrain mean we can use the existing roadways, rather than having to build tunnels or bridges. The cheapest time to build is now – it’ll only every get more expensive. Without sounding too hokey, this is about an investment in the future. We know that we can’t just continue to build bigger and bigger motorways, as we can’t sustain more and more cars.

Another benefit of remaking Christchurch as a rail city would be the connections with the rest of the South Island. Christchurch Airport is the arrival point for most tourists in the South Island. The airport link would allow them to explore the city without having to hire a car, and then, when they wanted to travel elsewhere in the island, they could make the journey by train. Even though 100% Pure is more of an aspiration than a reality, being able to pitch towards eco-savvy tourists is a big selling point for Christchurch and the South Island.

In the aftermath of the quakes, there was an optimism and a genuine hope that Christchurch could be remade to be a better place. Phrases like “the best little city in the world” were bandied about, but they’ve all but disappeared from the conversation. Though the city is developing in fits and starts, no-one would honestly say that it’s going to be the best little anything at the moment. The central city has new shops and offices and a beautiful library, but lacks life. This is a bold, expensive, forward-thinking plan that could do what 100 convention centres and justice precincts never could do – make Christchurch a fabulous, sustainable, liveable city for all.