As the death toll grows, the immunisation campaign is crucial. At a time like this individuals spreading nonsense is downright dangerous, writes Madeleine Chapman.

As of November 27, there have been 33 confirmed measles-related deaths in Sāmoa, 29 of them children. There have been 2,686 confirmed cases of measles in the current outbreak, in a country with a total population of less than 200,000.

Latest update: 2,686 measles cases have been reported since the outbreak with 249 recorded in the last 24 hours. To date, 33 measles related deaths have been recorded. Since the Mass Vaccination Campaign on 20 Nov 2019, the Ministry has successfully vaccinated 33,085 individuals. pic.twitter.com/QloorAzWBD

— Government of Samoa (@samoagovt) November 27, 2019

It’s believed the epidemic originated in New Zealand, where vaccination rates were at a historic low earlier this year. The rapid spread of the disease in Sāmoa was aided by low immunisation rates (less than half), particularly in the past 18 months. In July 2018, two babies died after receiving the MMR vaccine. The director general of health said the deaths were from human error – incorrect storage and incorrect mixing – and not the vaccine itself. However, administering of the MMR vaccine was banned throughout the country for several months and only started up again in April of this year. All children turning one in that time were not immunised. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated that in 2018, only 40% of 12-month-old infants received their first dose of the measles vaccine. In 2013 that figure was 99%.

“When they started vaccinating again in April, a lot of families who missed the first dose just didn’t take their kids back. Partly from no time but also limited access and it was a bit frightening,” says Sapeer Mayron, a reporter for the Samoa Observer.

“In terms of the anti-vaxxers, I really only see it online. The people here, they’re not necessarily not believing in the vaccine, it’s that they’re not exactly confident in the health system.”

Dr Nikki Turner, director of the Immunisation Advisory Centre, agrees. “There is a loss of confidence generally in the health services in Sāmoa that needs to be addressed. The issue now is to support them to restore that trust.”

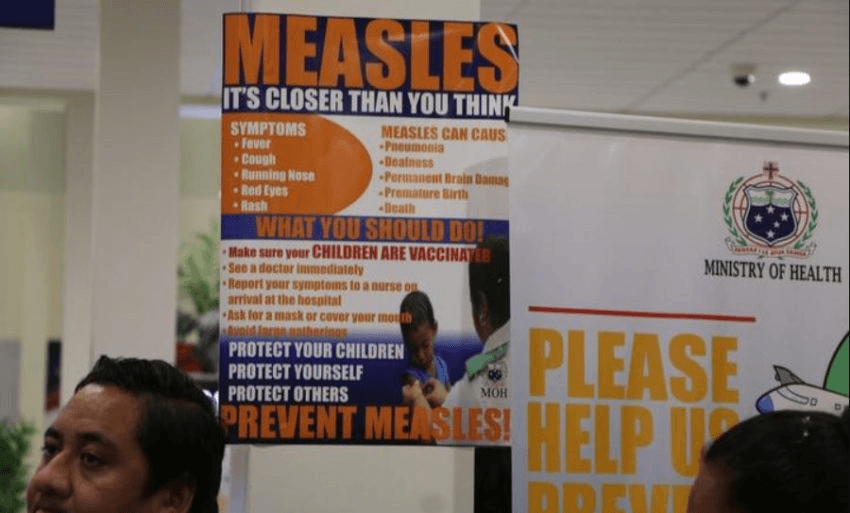

Huge efforts are being made to inform the Sāmoan public about the importance of immunisations and what to do if they or their children exhibit measles symptoms.

What doesn’t help these efforts is misinformation broadcast by people with a large audience but no expertise. Taylor Winterstein, an Australian blogger, and Eliota Sapolu, a former rugby player for Sāmoa, each have tens of thousands of followers on social media. They are apparently competing to see who can spread the most nonsense online.

Winterstein claimed that by declaring a national state of emergency and undertaking a mandatory vaccination schedule for vulnerable groups, Sāmoa is “turning into Nazi Germany”. Sapolu tweeted that the vaccines being administered are from India (true) and are “cheap” and “shit” (untrue) (wtf?).

The vaccines are from the Serum Institute of India, one of the largest vaccine manufacturers in the world. Their vaccines are approved by the WHO. Over half the children in the world will receive at least one vaccine manufactured by Serum Institute.

In Sāmoa, the reality is that most people simply want to do what’s best, and are willingly going for vaccinations, particularly those who live far from hospitals and are now being reached by mobile services.

“In my experiences out and about, the only resistance to the vaccination campaign and the measles effort I’ve noticed was when the government banned under 19s from travelling between Savai’i and Upolu [the two islands of Sāmoa],” says Mayron. “And that was because it was sudden and families were separated.”

Turner knows that just because such vocal theorists are in the minority doesn’t mean they are without influence. “When you’re dealing with fear in these situations, a few very vocal people with misinformation can do a lot of damage.

“From the World Health Organisation down, everyone knows that vaccines help to stop measles.”

When people are scared, they are vulnerable. Sāmoa is a scary place to be right now. Children are dying every day, and dozens of people are being diagnosed with a highly contagious, but entirely preventable, disease. The end is nowhere in sight so drastic measures have been taken to protect the most vulnerable groups.

What people like Winterstein and Sapolu are doing is not only frightening the most vulnerable. It’s outright dangerous.