Morgan Godfery tries to make sense of the last decade for Māori in te ao hurihuri, the changing world. Here he looks at the highs, the lows and the TBCs…

Taika’s interesting world

There are three roads out of Opotiki, the rural town where the Eastern Bay of Plenty becomes the East Coast. You can exit via the south, taking the Waioeka Gorge and retracing the route Te Kooti and his flock took to escape the colonial government. You can head west, back into the Bay of Plenty and the Pākehā world, passing the old Te Kooti Road on the way out. Or you can track east, down the coast and into the Māori world. 20 minutes in, passing at least three hard red, soft yellow Marae on the way, you reach Hawai. The road dips down from the hills and hugs the Pacific’s stone banks. The Raukūmara ranges roll out in front of you, thin finger peaks in the distance, and a green and white hoarding performs the necessary welcome.

Nau mai, haere mai, it reads.

You are entering the tribal lands of Te Whānau-ā-Apanui. First Nation people.

At this point a chorus breaks above the wave echoes and road hum. “E rere ra e taku poi poro-titi”. Sing it in tune! “Ti-taha-taha ra whaka-raru-raru e poro-taka taka ra poro hurihuri mai”. Keep up the beat! “Rite tonu ki te ti-wai-waka e”. When you make it to the end of the straights, climbing another sharp hill for another 45km turn, the soundtrack fades and James Rolleston walks into frame. “Kia ora, my name is Boy, and welcome to my interesting world”. This happens in my head every single time I pass that green and white boundary line. I blame Taika Waititi, the director who uses that welcome and warning sign to open his coming of age classic, Boy.

No one stands above and across this decade in the Māori world quite like Waititi does, at least culturally: Boy, the 2010 East Coast classic; the very Wellington What We Do in the Shadows in 2014; Barry Crump’s Hunt for the Wilderpeople in 2016; blockbuster triumph in 2017 with Thor: Ragnarok; and festival success this year with Jojo Rabbit. Waititi did in a decade what some directors take a lifetime to do, topping the New Zealand box office twice, breaking into Hollywood and its most lucrative market (Marvel), and winning critical acclaim all at the same time.

But Boy, and its predecessor Two Cars, One Night, a short film belonging to the 2000s, remain Waititi’s best. I remember when Boy made its theatrical release in March 2010 and a good number of critics, though not all, mistook its genre for ‘comedy’. In one sense, it is in that it’s a crack up. “Now, who knows what disease this sheep has? AIDS!.” But in another sense the film is nothing of the sort. Like almost all of Waititi’s work, Boy is about broken men. What they do to themselves and those close to them, and the havoc they leave behind. Whānau. Mothers. Sons. Alamein. Uncle Hec. Even Thor. Broken, for their own reasons and in their own ways, and all acting out hurt and healing on the world.

What distinguishes Boy is just how perfectly it captures the Māori world, in all the right colours. The accents we recognise. The mates we love. The nannies we knew. Once Were Warriors might mount a claim to best New Zealand film ever made, but it’s too cruel, too self-serious, and too violently regressive for anyone to ever hold it in affection or intellectual admiration. Boy does similarly serious work, but with the lightest touch. Rocky, Boy’s younger brother, is a social outcast but far from representing that as a stigma Waititi portrays it as a source of strength. “I’ve got powers,” Rocky tells Weirdo under the Raukokore bridge.

But the film did have its critics. Some scenes, admittedly, can come uncomfortably close to flippancy. Nan driving off on a week-long tangi trip is the sort of “back in my day” thing that did happen, but like the koros who would walk to school in the latest cow kicks, walking half the length of the North Island if they’re to be believed, today the angle is more stereotypical than archetypal. Off screen it’s Nan holding everyone’s lives together, and so using her as a punchline is less than she’s worth. But at the same time it’s hardly a coincidence that as soon as she’s out the gate and Alamein is in, Boy’s world turns inside out and upside down. And so for everything Boy and Waititi might come close to getting wrong, it nails so much more.

This is why the film is decade-defining, and after topping the New Zealand box office it made way for a rolling paepae in 2014. Toa Fraser’s The Deadlands, a landmark for screening entirely in te reo Māori; Himiona Grace’s The Pā Boys, a road tripper that isn’t quite what it appears, and James Robertson’s The Dark Horse, a drama confirming Cliff Curtis as probably the finest Māori actor ever. Curtis, a Fear the Walking Dead lead in 2015, tends to keep his head low – I remember spotting him few years ago, unrecognisable, in Dirty Dogs and a beard at Rotorua Airport – yet he deserves special credit as a mentor to up and coming local actors and as a producer with his cousin and filmmaking partner Ainsley Gardiner (Boy, This Is Piki, Merata: How Mum Decolonised the Screen, Herbs: Songs of Freedom).

Reo hits were popular again

It’s impossible to write about the decade in music without the customary mihi to Six60. The everyman band. The populists. The darlings of Western Springs. I remember in the band’s early years, 2011 especially, when breathas from lesser frat flats – mainly at Victoria and Canterbury – would make the pilgrimage to Otago to offer tribute (via a massive bender) to what was the decade’s insurgent sound. But was it, for the purposes of this piece, a Māori sound? Of course it was. The band’s first hit, ‘Rise Up’, owes a part of itself to Kora, the roots-reggae-funk-impossible-to-pin-down band whose sound defines the 2000s, and who this decade did the most extremely 2010s thing in focusing their creative energy into running an MMA gym.

Don’t Forget Your Roots, the band’s second hit, also owes part of itself to another 2000s star, this time Tiki Taane, the producer on their first album and another artist doing an extremely 2010s thing, chanting ‘Fuck the police’ at a gig in 2011 and spending a night in the cells for it. But on the wider point it really is a testament to Māori music’s crossover appeal that these collaborations were defining the decade, and opening space for others artists and for different forms. This year the poppiest artists and bands, from Benee to Drax Project, rerecorded their singles in te reo Māori, something unimaginable even 10 years ago.

But in the decade’s hall of fame it’s surely Stan Walker whose name stands above the door. For his music, yes. In [2010] his second album went [platinum] and in 2014 ‘Aotearoa’, a collaboration with Maisey Rika, Ria Hall, and Troy Kingi, the decade’s other standout stars, made it all the way to number two in the charts, an achievement in itself for a single entirely in Māori. Yet these days the Australian Idol winner’s music can sometimes feel secondary, acting more as a vessel for his charisma and a proximity to his pain.

In 2006 the teenage Walker found out he was carrying the CDH1 gene, an aggressive hereditary mutation that confers on its carriers an 80% chance of stomach cancer. “I know no one’s destined to have cancer,” Walker told Stuff’s Bridget Jones in 2018. “But I always felt like it was going to happen.” It turns out, tragically, his feelings were prophetic. Just over ten years after the diagnosis surgeons took out Walker’s stomach, attaching his oesophagus to his small intestines as a means of heading off the cancer.

The surgery alone is enough to bring any person low, let alone recovering and adjusting to a body without its digestive pouch. But complications also meant Walker had a collapsed lung, and a few months later surgeons were back, this time taking out his appendix. “I had these little dips, these deep, dark dips… It got worse and worse. Next minute, I’m in hospital again. After a day they wanted to do emergency surgery for an infected gallbladder, but I said ‘no, tonight I have a dinner with the Prime Minister’”

From the small things I know about Walker this seems like classic Stan: even in the worst pain imaginable he was honouring his commitments to others. In 2018, at the centre of his punishing recovery and adjustments, he took the One Love stage because that’s what professionals do. “There’s part of me that’s still numb,” Walker said a couple months after One Love. “Then there’s another part of me that wants to live my best life, make the best music.” And at the decade’s close, cancer-free, no one doubts he is, the personal struggle granting his music a special capacity for commentary. His latest hit ‘Give’, a single that might come across as a little “hopey changey” in another person’s voice, comes across as an honest and earnest encouragement in Stan’s.

We were all watching TV, until we weren’t

One of the decade’s surprising shifts, not necessarily in its happening but in its speed, was the te reo Māori take off. One year the best we could expect was Simon Dallow’s ‘Kia ora, good evening’ on 1News and the next year Maiki Sherman was delivering a news reports entirely in te reo (only for Māori Language Week, mind you, but the point stands). Guyon Espiner and Jack Tame were mihi machines on Morning Report and Breakfast respectively. Even Air New Zealand was in on it, dropping kia oras at every boarding gate. The language advocates call this normalising the language, and it certainly is, but I prefer to think of it as a restoration. The first nervous, promising steps to reclaiming the first language of these islands.

I suspect you can date the language’s media take off to 2012. That year the Māori Language Commission undertook a rebrand for language week launching ‘Arohatia te reo’. For one reason or another – whether it was good marketing or simply good timing – the theme took off. Stickers, badges, parliamentary questions entirely in Māori. Parliamentary answers entirely in Māori. The language was reaching as deep as its ever been in New Zealand society, shaping a new attitude to Māori and a better public understanding of just what it means to live here.

But these changes, at least the quiet ones, were probably in motion a little earlier than 2012. 2004, when Māori Television broadcasts its first transmission, is probably when the first signs were appearing and 2011, when the station was at the height of its powers, was probably confirmation something big was happening. That year it felt as if everyone was watching. Julian Wilcox was in the Native Affairs seat with Mihi Forbes following after. Jenny May-Coffin and Glen Osborne were on the Code couch. Producer queens and kings like Wena Harawira, Annabelle Lee-Mather, and Colin McRae were making it happen behind the scenes. Jim Mather was in the bosses’ office. And in a move no one was expecting, the Rugby World Cup would air on the channel later that year.

Come the quarter-final Māori Television was pulling in over 500,000 viewers to TVNZ1’s 420,000. These are ratings the channel’s architects could only dream of in 2004. As you might expect, the ratings went on to dip when the tournament was over, but announcement had already been made: Māori Television was here to stay. Public awareness of its other shows, from Native to Code to its documentaries and foreign films, and its influence was at an all time high.

Until, in 2015, it wasn’t. New management was in and the channel’s stars were out. Viewership and influence collapsed.

Reading and writing was cool (but fraught)

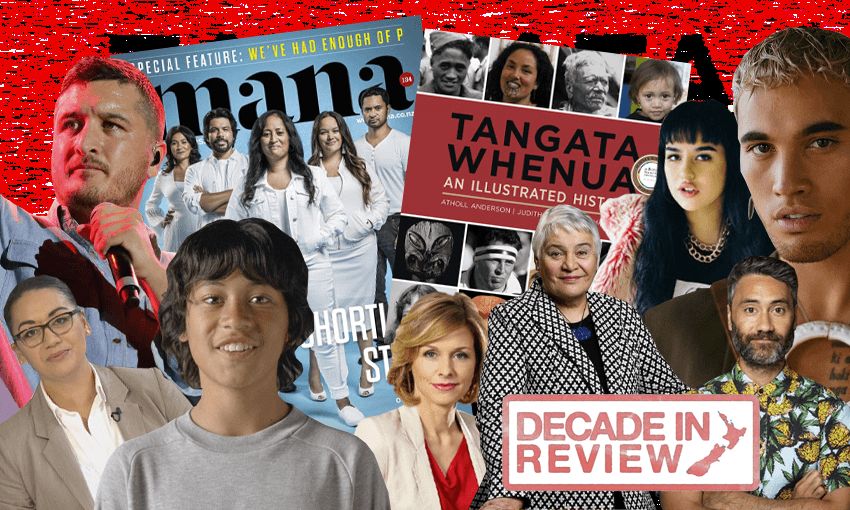

2014 was a landmark year. It was an election year, and it was the year Tangata Whenua: An Illustrated History went to print. In bringing together a list of the greatest works of [Māori] non-fiction ever (it’s worth re-reading the list, by the way) Ātea editor Leonie Hayden, award winning journalist Aaron Smale, Tangata Whenua’s publisher Bridget Williams (who was of course too gracious to list any of her own work) and myself put Tangata Whenua at the very top of our list. It was obvious, even after only a year in print, the book was a landmark work expanding the scope of Māori history, weaving together knowledge from archaeology, anthropology, linguistics, law, political science and of course oral history. It was brilliant.

But the decade for Māori writing ran hot and cold. Mana Magazine went out of print in 2017 after its owner Derek Fox refused to relicense or sell the masthead to Kowhai Media. The “indefinite hold” on the magazine, as Fox put it, left an outrageous gap in Māori writing and society. Over its history the magazine was responsible for iconic covers – from the Māori Queen to a naked Carol Hirschfeld (most copies of which were lost in a mysterious fire) – and some ground breaking journalism. It was Aaron Smale in Mana’s pages who broke open the abuse in state care scandal, and revealed the appalling number of families living in cars in Tāmaki Makaurau. Under Leonie Hayden’s editorship the magazine’s art, film, and music coverage was unrivalled, adding to the powerhouse political coverage nurtured and perfected under previous editors like Gary Wilson.

The first ever Mana issue went to print in 1993. The magazine came about more as a chance than anything else with Fox and Wilson, at the time running Māori radio and television, simply deciding to give it a go. Magazines were still selling well in the 90s, and as the two editors knew from their work in broadcasting there were so many stories waiting to be told. Why not? And through good work and a little luck things went their way. Over Mana’s long run it was everything a magazine should be: relevant, thanks in good part to the many Māori professionals willing to give it a shot; widespread in its reach with over 100,000 readers at one point; and a nursery for some of the best Māori writers and journalists of their generation.

For that reason alone the magazine folding was a tragedy. It was fragile time. At the same time Mana was put on hold the Māori blogosphere, such as it was, was collapsing after burning bright and briefly from 2011 to 2014. That left the legacy media as the last host for Māori writing. Bridget Williams Books, especially with its BWB Text series, put in the work to find and publish Māori writers: Hirini Kaa, Aroha Harris, Rachel Buchanan, Jade Kake, and (shamelessly) me. The late Tahu Potiki was writing regular columns for The Press. And crucially Leonie Hayden and Gary Wilson and Tapu Misa were striking out under new online mastheads, Ātea and E-Tangata respectively.

It was a significant moment, and four years after E-Tangata’s launch and three years after Ātea’s it’s impossible to think Māori writing could have ever got by without them. Both platforms are smashing it, providing a space for writers to write as Māori. Moana Maniapoto, a legend as a musician, proved she can master any art form she turns her hand to, publishing challenging essays and op-eds for E-Tangata. Nadine Anne Hura was publishing, both at E-Tangata and Ātea, the best creative non-fiction you can find. Emma Wehipeihana, Miriama Aoake, Josh Hitchcock, and many more were publishing the best thinking at Newsroom, Vice, and other outlets.

At Victoria University Press and vibrant independent publishing scene Māori poetry was having a decade-long moment too. Hana Pera Aoaka, essa may ranapiri, Tayi Tibble, Alice Te Punga Somerville (who also writes gorgeous prose) and too many more to name were releasing terrifyingly good work in that their latest piece is almost always better than their last. In fiction Tina Makereti, Paula Morris, Patricia Grace, Witi Ihimaera (this time in non-fiction) and so many others were publishing career best work. All asking, I think, in their own ways the most important question: how do I belong? Am I woven into the tukutuku or am I a dangling thread?

Long live the Māori Party

People with long memories will remember the last Labour government’s dying days. 2008, Helen Clark is the soon-to-be-former Prime Minister and the Māori Party, contesting only its second election, is going all in with the ihi of a thousand paddlers, the wehi of a hundred poi dames, and the wana of the mother of Māori politics herself: Tariana Turia. In that landmark election the party came home with five seats, a record catch and only the second time in more than half a century that a party managed to haul back most of the Māori seats from Labour. After the Foreshore and Seabed Act’s raupatu in 2004, and police invasion in Tūhoe country in 2007, the win felt like justice.

Anything was possible.

Yet it took the 2010s only a few years to snap everyone out of it. After early wins, from signing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2010 to implementing the Takutai Moana Act in 2011, the party waka was taking on water. The leadership in Turia and Pita Sharples, facing a dark choice between supporting an increase to GST or losing seats at the government’s table, went with the former, lending their votes to Budget 2010. Hone Harawira, the caucus radical at the time, was furious, and he let everyone in the media know it calling the choice and policy “an attack on the poor”. Not even a year later he threw his paddle overboard, opting for the Mana Movement waka instead.

Conventional wisdom says attack politics will fail. Focus groups and polls usually conclude voters have had it up to here with tribal bickering and petty partisanship. They would prefer politicians to work across the house. It’s a lovely sentiment, but usually the opposite happens and voters reward negative campaigns. Labour spend nine years on the attack, going as far as accusing the party of “selling out” for voting for amendments to the emissions trading scheme. In 2017 Andrew Little said the party actions in government were not “kaupapa Māori”. Labour won that election bringing home the seven seats and a record 13 Māori MPs.

In hindsight the problem is obvious: the party’s relationship with National. Political commentators, including this one, were broken records in the years 2008 to 2017 arguing the Māori Party’s supply and confidence agreement with the rich man’s party would doom it sooner or later. National regularly polls under 10% in the Māori seats, and so a compromise with the most unpopular party in your own constituency never made sense. It’s as good as throwing the game. Add in ‘Jacindamania’ in 2017, and the fact the party made its peace with power nine years earlier, and the election was always a done deal.

So come the close of the decade Labour is back. But that comes with its own snags. The government said no to a capital gains tax, no to most of the recommendations from its own welfare working group, and a “maybe” to returning Ihumātao to its people. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern came to power promising a “politics of kindness” and a “transformational government”. It fails on the first count, refusing to lift all sanctions on beneficiaries, and fails on the second, content to preside over the system as is. Even the good things – like lifting the minimum wage – are things that were happening under the last government anyway (there is something to be said, though, for the fact this government is lifting the minimum wage more than the last government was).

That political gap leaves it to others to pick up the ideological slack. SOUL, mainly, the kaitiaki group responsible for almost singlehandedly re-energising the wider left. Others, too, are doing their bit to remake the country. Ngāti Kahungungu are transforming the way we care for “vulnerable” families, taking the initiative after Oranga Tamariki’s catastrophic failures. Ngāti Ruanui are taking on Big Oil too as the government continues to allow onshore prospecting and extraction. In my mind, if people remember the end of this decade for anything, it’s surely that activism and those activists, people offering as much hope and promise as the cultural landmarks who were defining the decade’s open. In short: we’re with them, this decade and the next.