In the late 1970s, workers joined Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei to stop luxury housing at Takaparawhau – a landmark alliance of unions, Māori and environmentalists.

During the strike waves of the 1960s and 1970s, “black bans” – in the unfortunate language of the time – were a frequent form of work stoppage. They involved unions banning certain forms of work for various reasons. For example, in New Zealand during the 1970s, unions banned trade with Chile (to protest the Pinochet dictatorship) and France (to protest French nuclear testing in the South Pacific).

Green bans were an innovative progression from black bans. They were ecological political stoppages pioneered in 1970 by Australian construction workers’ unions. The Builders’ Labourers’ Federation placed green bans on disputed land, natural habitats, buildings, and working-class neighbourhoods threatened by developers (see Rocking the Foundations). They only did so after a genuine request from a community group. After a green ban had been placed, construction workers would then refuse to work on the site. Hence, green bans were both a form of workers’ control and ecological control. Their remarkable success in halting expensive construction projects led to repression. However, many of the bans are still observed – for example they saved several historic Sydney neighbourhoods.

Many have championed green bans as examples of how unions can undertake successful direct action to support environmental concerns in this age of climate change, and to subvert the view that the labour movement fundamentally clashes with the environmental one. While the Australian green bans have gained some global recognition, the ones in New Zealand are almost unknown internationally. In Aotearoa, greens bans were also trailblazing – they were indigenous adaptations of the Australian practice. They were placed to support Māori concerns over their alienated land and fishing grounds in the late 1970s.

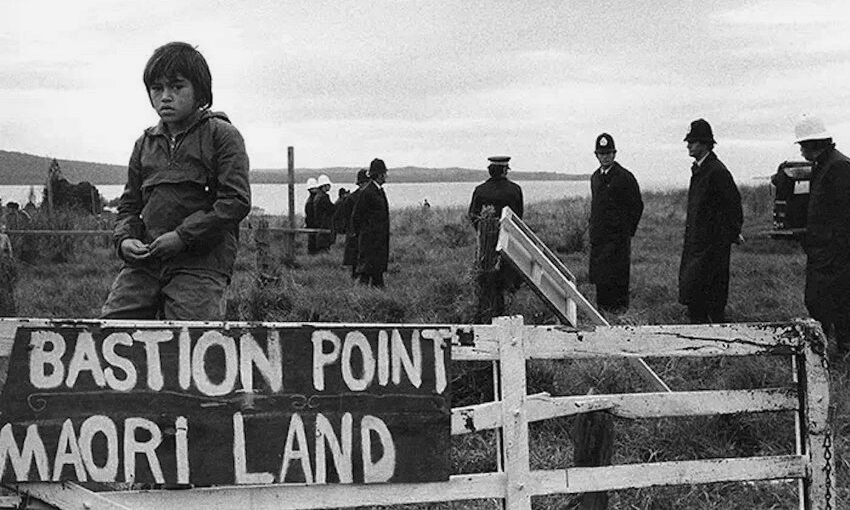

The most significant green ban in New Zealand was at Takaparawhau/Bastion Point Auckland in 1977–78.

Takaparawhau was the site of a watershed Māori protest against the alienation of their land, and the green ban placed to support the land occupation there represented the most significant workers’ stoppage in support of Māori in New Zealand history. It was also a globally important example of practical labour union support for indigenous land rights.

In the 1840s, Ngāti Whātua had gifted much of its Auckland land to the British governor. They retained the Ōrākei land block (which included Takaparawhau, so they could still live on their traditional lands). Yet, despite an 1869 court ruling that the 700-acre Ōrākei block was inalienable, the settler government either purchased or compulsorily took almost all of that land by 1951.

In the early 1950s, the government evicted Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei from the tiny amount of land they had left, and burnt their communal meeting house and private houses to a cinder. Joe Hawke, a leader of the Ōrākei Māori Committee Action Group (ŌMCAG) which organised the occupation of the land in 1977, was evicted as a youngster along with his family after his home was torched.

A belligerent National government, led by prime minister Robert Muldoon, had decided to develop Takaparawhau – which was then a large grassland area owned by the state above a headland – into a luxury private housing area. The land was prime real estate with an ocean view. It was also beside a working-class state housing area and “Boot Hill”, where many Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei had been relocated by the state after their early 1950s eviction. The Ngāti Whātua iwi and supporters then occupied or repossessed their land, and unions placed a green ban in support.

In 1977, Hawke wrote in the Socialist Action newspaper of the 700 acre Ōrākei block:

“Only a quarter acre was left now – the urupā or burial ground… Today at Bastion Point, the Ngāti Whātua are fighting against the government sub-dividing what is rightfully their land… Our people will no longer submit to disgrace and humiliation. Bastion Point represents the struggle of the Ngāti Whātua for the return of their mana, honour, and ancestral land.

The green ban was placed before the occupation began to stop bulldozers rolling in. It occurred after ŌMCAG requested that the Auckland Trades Council (ATC) ban any work on the site. The ATC was the Auckland region coordinating body of private-sector unions affiliated to the New Zealand Federation of Labour. The acting ATC president Dave Clarke (of the Te Paatu tribe and the Seamen’s Union) agreed to it, and the green ban was later confirmed by the full ATC executive.

ŌMCAG representatives then hurriedly contacted the workplaces that would have been required to begin construction work on the land to give practical effect to the green ban. Union job meetings were arranged with such workers, including road metal suppliers and truck drivers, and they voted unanimously to support the ban and to contribute money to the occupation. The unions they contacted contained many Māori, including the labourers and drivers’ unions. Consequently, no development began at Takaparawhau such as bulldozing and infrastructure work like roading.

On January 5, 1977 the occupation began. A large tent town was established to occupy the land. Thousands of supporters visited. Gardens were dug, buildings erected and a large marae built. Some of the building materials were sourced by unionists and many participated in, or supported, the occupation.

Four months into the occupation, the government threatened to evict the occupiers. They considered the protesters squatters and the tents a shanty town. Despite defying trespass law, the government “had to back off because of the widespread public support for our stand,” according to ŌMCAG.

The committee continued to send its representatives to union meetings to gain support and reinforce the green ban. After meetings, teachers, wharfies/dockers, seafarers, railway workers, construction workers, nurses, meatworkers and others donated money. Brewery workers gifted a weekly levy from their paychecks to the occupiers. However, Syd Keepa – a truck driver union member – is quoted by Cybele Locke in Comrade: Bill Andersen – A Communist, Working-Class Life as saying that some union officials sold the green ban to unionists as an action opposing the efforts of prime minister Muldoon “to build rich people’s houses on there” to circumvent some union members “who were a bit iffy on Māori rights”.

In April 1978, an injunction was granted to stop protesters trespassing on, using or occupying land at Takaparawhau. ŌMCAG, in a “special appeal to workers”, called for workers to defend Bastion Point and “show class solidarity with us in our struggle”. The ATC called for a mass union picket if an eviction attempt was made. According to Syd Jackson – an ATC executive member and major leader in the Māori sovereignty movement – workers at several job sites went on strike to rush to the occupation when eviction threats were issued.

Despite these efforts, the state forcibly evicted the occupiers and arrested 222 people on May 25, 1978. Hundreds of supporters, including unionists, could not reach Takaparawhau as the police had sealed off all roads in the area. The occupation had lasted 17 months. Government workers, who were in a conservative public sector union outside the ATC, scabbed on the green ban by demolishing the buildings. The early 1950s eviction had been repeated, despite mass non-violent resistance.

To ŌMCAG, the government had taken off its “mask of democracy” and showed its “true face of state force violence in using 600 police, Army, Navy and Air-Force personnel…Bastion Point was to be subdivided for a rich elite. The spirit of Māori and Pākehā people in the face of massive state force was tremendous”. Many unionists were among those arrested. The 222 arrests made it one of the largest mass arrests of protesters in the country’s history.

Unions locally and globally have generally neglected indigenous issues. The Takaparawhau green ban was an example of a successful practical alliance between indigenous people and unions, as well as environmental action. Its apparent defeat due to state repression turned into a win when, after a Waitangi Tribunal hearing in 1987, the government eventually returned most of Takaparawhau to Ngāti Whātua – the land had remained undeveloped, and the green ban remained in force after the eviction. Today, much of that land is a public reserve, Takaparawhau Reserve, “for the benefit of all” and managed jointly by Ngāti Whātua o Ōrākei and Auckland Council.

The occupation is now celebrated as a landmark event. It was a turning point in the Māori renaissance. By the 1970s, Māori had lost around 95% of their land since colonisation through war, confiscations and purchases. Takaparawhau was one of the first parcels of land to be returned to Māori through the state’s attempt to redress grievances, which began in the mid-1980s through the Waitangi Tribunal process. The occupation opened the eyes of many Pākehā to the systemic and ongoing nature of land alienation and racism.

The green ban was also a high point in workers’ direct action to support Māori land rights. Māori were overwhelmingly concentrated in the blue-collar working-class, and frequently played a central role in many militant unions and strikes. The mutual connections and traditions of solidarity with fellow unionists that were developed during the 1970s – the largest period of strike and protest activity in the country’s history – laid the foundations for the green ban. Several other green bans were placed on traditional fishing grounds and alienated lands in the 1970s. But after unions were progressively defeated and then hollowed out in the 1980s and 1990s by de-industrialisation and neoliberalism, green bans were not placed again as far as is known.

This article was originally published on the Brazilian social history website LEHMT (Laboratory for the Study of the History of Worlds of Labor) as part of their global series on places of significance in working-class history.