“I don’t think I’ve ever heard a more succinct summary of the way that sexual violence lives in the air that we breathe,” writes Alex Casey of Boys Will Be Boys.

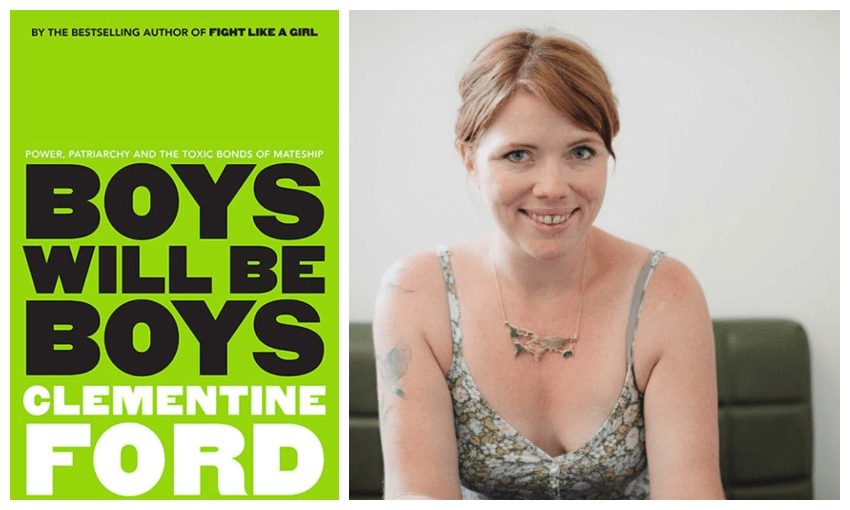

I’ve never written a book review before, so I’m assuming it’s totally canon and intelligentsia to start by talking about the cover. Boys Will Be Boys, Clementine Ford’s furious and phenomenal second book, is the exact same neon green as the sentient goo in sci-fi comedy Flubber (1997). If toxic masculinity had a physical form, I think it would be a lot like flubber. Even though men (Robin Williams) think it’s benefiting them, flubber ruins everything in its wake. When left unchecked, it can be fully absorbed, turning some men (Tim Curry) into absurd, violent, twitching demons.

It’s this oozy green of the patriarchy and “the toxic bonds of mateship” that get obliterated in feminist writer Ford’s latest book. Walking to work last week, I was thinking about how best to summarise Boys Will Be Boys. How do you “review” something so blistering, so thoughtful, so ferocious in a way that would still entice those who need to read it the most (men)? Maybe I was just being hysterical, maybe I was on my period, maybe I was overthinking it’s magnitude because I famously have a “sandy vagina” (brave commenter on The Spinoff, 2015).

Lost in those thoughts, I dropped my phone on the footpath because I forgot my stupid fucking pants don’t have stupid fucking pockets, because no women’s clothes have stupid fucking pockets. And then, when I bent down to pick up my stupid fucking phone that had slipped because I didn’t have stupid fucking pockets, a van full of men drove past, tooted at my butt and yelled “woo!” like I was performing some kind of intricate sidewalk sex show. The green goo began seeping out of the drain below me. Flubber.

Where her first book Fight Like a Girl read like a feminist manifesto and a call to arms for women everywhere, Boy Will Be Boys shifts the spotlight to examine how the patriarchy and gender roles affect men as well as everyone else on this godforsaken planet. Tackling something as vast as the patriarchy is a mammoth task, so Ford takes what I call “the Michele A’Court approach” and eats the elephant with a teaspoon, breaking it down into essays ranging from the ‘not all men’ movement to the representation of men and women in popular culture.

Armed with statistics, studies, and reference points spanning Audre Lorde to Return to Oz (1985), Ford constructs bulletproof arguments and devastating snapshots of a gender shitshow. There are grim facts about childhood classics (Mulan is 77% men talking, Aladdin is 90%) and serious analysis of how crucial representation in pop culture is. Namely, if you’ve grown up with “men being heroes, men being villains, men being funny, men being serious. Men – so many men – navigating the world with purpose and adventure,” then where do the rest of us fit in?

Beyond realising that all movies are fucked – even Frozen – every foggy interaction with sexism and gender violence you’ve ever had will be pulled into sharp focus. A chapter about how the perceived primal sexuality of men and the ‘purity’ of women reminded me of how my primary school banned girls from wearing Canterbury shorts (not long after I made them cool *sunglasses emoji*) because they were deemed too short. I was 12 years old, and the only fashionable thing I’ve ever done was ripped away from me for fear of how boys might react.

Taking on those flubber-like qualities yet again, rape culture and sexual violence permeate every chapter of Boys Will Be Boys, some of which you may need to steel yourself for. I may also have ruined the vibe of our sunny long weekend holiday by loudly declaring “I just don’t want to read about rape anymore” on the beach, but I meant every word. Ford takes us on an extremely uncomfortable whistle-stop tour of sexual violence, be it Brock Turner, Steubenville, Donald Trump or Dane Cook and the ongoing defence of rape jokes.

For all the many, many intelligent words Ford has written on the topic of rape culture in her two books and hundreds of columns, five simple words packed the biggest wallop: rape is in the room. Rape. Is. In. The. Room. I don’t think I’ve ever heard a more succinct summary of the way that sexual violence lives in the air that we breathe. Make no mistake, every woman that you know has a story of sexual violence or harassment, or knows someone who does. Ford makes that abundantly clear, before posing the biggest question of all: who is doing it to us?

Although Boys Will Be Boys draws primarily from Australian examples of sexism and violence, New Zealanders can hold their heads up high in the knowledge that our culture is entirely just as bad. We love to stay on par with the Aussies, don’t we? They have the AFL scandal, we have the Chiefs scandal. They have their misogynist named Tony (Abbott), we have ours (Veitch). Before you get defensive, consider the fact that police knew about the Roastbusters page for at least two years and ridiculed this Beast of Blenheim survivor when she came forward.

When Ford wrote that “the vision of Australian mateship has always felt distinctly male to me, and I’m not really sure how I’m supposed to fit into it,” my eyes immediately rolled back into my head and conjured up a vivid vision of Speights-drinking, barbeque blokeyness. You know that tunnel full of shocking images that Willy Wonka drags the kids through in the original? It’s like that, but instead of worms and bugs, it’s John Key wearing a ‘I’m not sorry for being a man’ t-shirt, Stuff comments and Thane Kirby on loop. I’m not sure how I’m supposed to fit into it.

For all of the infuriating, terrifying parts of Boys Will be Boys, I can’t overstate Ford’s withering wit. She describes incels as a “turducken of toxic masculinity, entitlement, self-obsession and rank misogyny” and has the most brilliant use for yoghurt culture since at-home thrush treatment. Throughout, she takes care to explain the ways that women of colour, LGBTQIA+ women and disabled women come out of the patriarchy even worse. You won’t get any millennial pink #leanin guff here, but instead an ongoing dissection of her cis white privilege.

And still, somehow, there’s lots of jokes.

Beginning and ending with her own personal reflections on the birth of Ford’s son, Boys will be Boys is wrapped with a tenderness and an empathy that even the most incensed, feminazi-hunter MRA Reddit user would find hard to deny. “I want this world to be different for you,” she writes, “I want you to have more choices about the kind of boy you want to be.” Waah. Look, even if you hate feelings, Boys serves as an incredibly thorough time capsule of the modern fight for gender equality. It’s also some of the most essential and electric feminist reading of the year. Buy it for the special man in your life.

Boys Will Be Boys: power, patriarchy and the toxic bonds of mateship by Clementine Ford (Allen & Unwin, $37) is available at Unity Books.

Clementine will appear onstage at the Freemans Bay Community Centre in Auckland, on Tuesday, November 27; and at LitCrawl in Wellington on Friday, November 22 at Victoria University’s Memorial Theatre, and Saturday, November 24 at the Double Denim HQ in Cuba St.