‘I finished This is Pleasure at about 4am on a Sunday. I hadn’t been able to sleep – I’d had an uncomfortable interaction with a powerful person, and it was keeping me awake …’. Pip Adam on a book that challenged and changed her.

From where I’m typing this, I can see a copy of Bad Behaviour, Mary Gaitskill’s 1988 short story collection. I don’t like to get too far away from it when I’m writing. It has this power to make me work harder. Whenever I’m contemplating the easy way out, if I catch a glimpse of it a voice in my head says, “Do you really want to do that?” In life, pleasure is complicated, pain is complicated, power and sex are complicated. But I didn’t realise this complication could be replicated so keenly in literature until I read Bad Behaviour. Nothing is easy in Gaitskill. Her new work This is Pleasure is possibly her most uneasy.

First published online at the New Yorker in July 2019, This is Pleasure is now also available as a hardcover book. The book, published in November, requires a degree of publicity and marketing – especially, I guess, because it’s available online for free – and it’s this marketing that began to unnerve me. There’s an urge to describe a book in simple terms, so people can tell if they want to buy it or not. A phrase that sticks in the first interviews and reviews is that This is Pleasure offers a “more nuanced view of #MeToo”. The book sounds worrying in the abstract (to me at least) – a story of sexual harm told through the voice of the abuser, Quinn (Q.) and Margot (M.) a very close friend of Q.’s who believes she has protected herself from his sexual predation. A review in the Guardian says, “There’s room to feel sympathy with the flamboyant, roguish Q, and some readers will; it’s an astonishingly humane characterisation, articulated within mutable social dynamics.”

Gaitskill’s complication has a way of rendering terms like “good and evil” ridiculous and I’m not sure if I’m ready to have this degree of ambiguity extended to an abuser and their supporter. I know how hypocritical this sounds – I’m willing to extend this complication to some characters and not others. It’s an irrational discomfort but I feel invested in Gaitskill’s work in a way I don’t in others. I feel like there’s so much more at stake here than just a book – I found something of myself in her work and I’m not sure I want to share that with people who do sexual harm or the people who protect them.

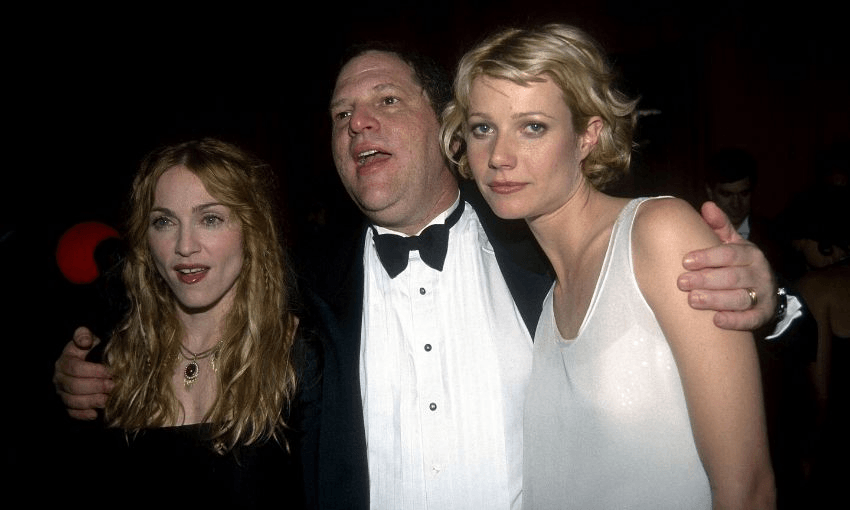

I’m a reader forged in Lolita and American Psycho – all the terrible people nuanced through beautiful language into complex humans with perspectives of their own. Most of the writers I read in my 20s and 30s have turned out to be terrible people themselves. The backdrop to my burgeoning sexuality was independent films produced by Harvey Weinstein. I’ve spent years trying to undo this cultural conditioning and Gaitskill has been a huge part of a journey home of sorts, toward a self-determination of desire and a renegotiation of my relationship to power. An un-teasing of my black and white ideas of good and evil – many of which were put there by people who did harm. These early stories, the ones I’ve tried so hard to out-run, were often used to characterise me in a way that made it possible to control me. These are the things I brought to Bad Behaviour when I first read it in 2006. The book didn’t give me answers to the questions I had about how to live but it was a huge help in revealing the things I’d hidden under other people’s stories of who I was and what I wanted.

I finished This is Pleasure at about 4am on a Sunday. I hadn’t been able to sleep – I’d had an uncomfortable interaction with a powerful person, and it was keeping me awake. After finishing the book, I went to the bathroom and found myself running back to my room afraid something would ‘get me’ if I walked. During the interaction that was causing me trouble in real life I’d felt powerless, I’d felt stupid, but most of all, I’d felt like my story was being re-written by someone else – like I was being redefined by another person’s actions. And I think that’s what I was reacting to so strongly in This is Pleasure. In the unrelenting voice of the abuser and his defender and the screaming absence of an accuser’s voice I felt like I’d been hit by all the narratives used to restore the order of the rape culture – she liked it, she wanted it, she overreacted, she’s crazy, she shouldn’t have dressed like that, or walked like that, or come into my office by herself.

I felt that by giving voice to these arguments Gaitskill was complicating something that didn’t deserve to be complicated. At first, I felt betrayed, then I launched into justification. I started frantically making excuses as to why that wasn’t what the book was trying to do. All these justifications were superficial, based on Gaitskill’s gender and her past writing. They were the weakest of justifications, ones based on the writer not the work. As the morning wore on, I found myself sinking unhappily into the idea that maybe this was just another piece of culture that attempts to make us forgive abuse and question victims. When I finally stopped the justification and surrendered to this idea, I was able to feel what I was feeling, rather than think what I was thinking and I was able to recognise – in my body – that this book apologises for nothing.

In an attempt to re-introduce a voice of a person at the receiving end of someone else’s power and sexual attention, I re-read Gaitskill’s story ‘Secretary’ in Bad Behaviour. It had been a long time since I’d read it and in my head it had been superseded by my memories of the 2002 film of the same name which Gaitskill wrote the screenplay for. I looked at some of the trailers for the film and it was how I remembered it – an almost uplifting story of a woman who finds her kink as her boss’s submissive. It made me wonder: maybe that was what This is Pleasure was up to. Maybe Q. is just a masochist in search of a sadist and maybe I’m being a prude. This thought immediately made me feel almost physically ill.

What I found when I re-read ‘Secretary’ was completely different to the hijinx of the film and it helped me understand some of the machinery of This is Pleasure. ‘Secretary’ is an extremely uncomfortable read. The narrator is simultaneously repulsed and excited by her boss’s escalating sexual behaviour. She has no power in the situation. In a HuffPost interview on the launch of her essay collection Somebody with a Little Hammer, Gaitskill talks about those devastating encounters where people say yes, out of the fear of saying no. ‘Secretary’, and perhaps all of Gaitskill’s work operates on this knife edge. ‘Secretary’ is an extremely unsettled story largely because, as a reader, I felt the same simultaneous revulsion and excitement in my body as I read the story. Because of this undeniable physical reaction I felt like I wasn’t learning about the characters as much as learning about myself.

I think there’s a tendency to understand this type of feeling as sympathy. I think fiction has a particular gearing toward the type of sympathy the Guardian review is suggesting. But I think Gaitskill is up to something much more terrifying in This is Pleasure than making me feel sympathetic toward Q.

Gaitskill has a way of almost absenting herself or any authorial voice from the work. There’s a sense of reading the events of her stories unmediated. I’d suggest, the effect of this lack of a moral compass is to make us far more implicated in the work. There’s no one telling us what to think or who to trust or that we’ll be okay – no one telling us how to be a decent human being in this situation. I think this inevitably turns the questions of the book back on the reader. I’d suggest that what I was reacting to so strongly in This is Pleasure wasn’t the monsters of Q. and M. but my own participation in rape culture – my many silences, those ingrained thoughts put there by someone else but inevitably my responsibility, the ways I misuse my privilege and power, my resistance to calling powerful people to account when it risks that privilege and power. This is what I thought would ‘get me’ as I ran back to my room in the dark.

What makes This is Pleasure so terrifying isn’t the risk that someone will tell us that rapists are okay, but that we have to decide for ourselves. In almost exactly the same way that Bad Behaviour had 13 years previously, This is Pleasure challenges me to learn something about who I am and what I believe. There is, of course, a problematic shadow text in the available reading outlined in the Guardian review: I imagine another person reading this book and finding justification for their own terrible behaviour, and this challenges me to learn something about the world I live in.

So, in the end, this is how I’m left after reading This is Pleasure – knowing more about myself and knowing more about the people and systems I live with. Most of what I know I wish I didn’t. I think finally, the effect of Gaitskill’s unmediated stories is the complete absence of someone to direct us away from the awful.

This is Pleasure by Mary Gaitskill (Pantheon, $18) is available from Unity Books.