Stephanie Johnson luxuriates in the new Julian Barnes novel – a story of adultery which “wrestles with the deepest conflicts of human existence.”

Julian Barnes may be seen as a leading exponent of the Hampstead novel. This is, in England, a pejorative term, even though great writers such as Margaret Drabble and Margaret Forster have been so ineptly labelled. In its broadest definition Hampstead novels concern themselves with the comfortable middle-class. White-skinned characters are well-educated, articulate, and partial to the forbidden fruit of adultery. They do not wrestle with the questions to which New Zealand writers frequently return, such as racism, isolation and social unrest. The Hampstead novel is an entertainment. At its lightest it’s a soak in the bath with scented candles and half an inch of scotch. At its most complex it keeps you awake while it wrestles with the deepest conflicts of human existence.

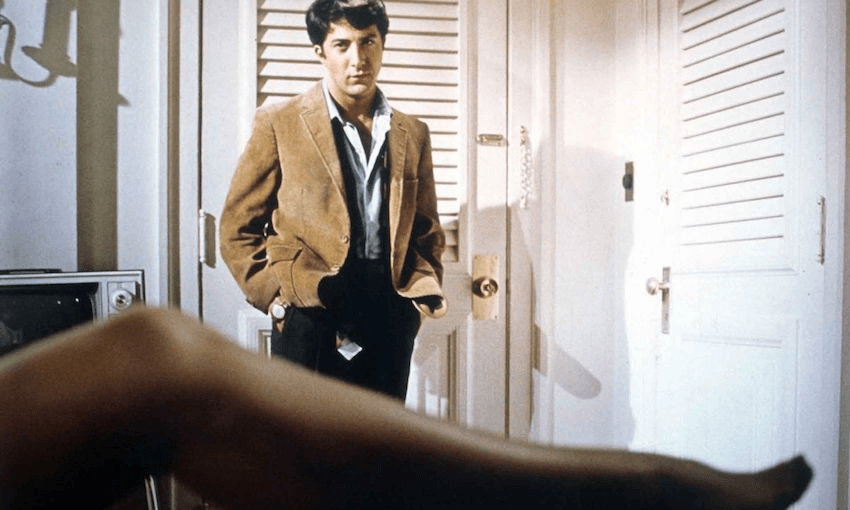

Barnes’s latest novel is both light and heavy. It’s a love story, a story of adultery, beginning with the narrator asking himself what he thinks of as the only real question: “Would you rather love the more, and suffer the more; or love the less and suffer the less?” Early on he wonders whether “the time and the place and the social milieu are important in stories of love” (surely they are?) before he goes on to give a detailed description of the village south of London in which he grew up. There are only two television channels and the chemist is not yet selling contraceptives. Later, when Susan Macleod enters the story, she makes more than once the statement that her generation are all played out, that the war took the best of them. So we can deduce that we are in the early 1960s.

Narrator Paul returns us to the year he was 19 and home from university for the summer holidays. He’s bored and rather snobbish about the locals, so his mother suggests that he join the tennis club, where he might meet a nice young woman of “Conservative tendencies.” Paul signs on, doing his best to ignore the Carolines and Hugos and jolly what-ho’s, and meets instead the woman who will disrupt his life and change it forever. Susan is 48, married with two daughters around Paul’s age, and more bored than he is. She refers to her husband as Mr Elephant Pants and tells Paul that they haven’t had sex for 20 years. She introduces him to her only real friend Joan, who smokes heavily, knocks back the gin and lives alone with a mob of dogs. Joan becomes the wise woman of the tale, a kind of mentor for Paul.

Although the story is being told in recall, which would allow the older Paul, the teller of the tale, to interject with statements of hindsight, Barnes resists the temptation. Guileless, innocent and full of hubris, young Paul allows himself to believe that he and this woman almost 30 years his senior are the same in spirit and that the age gap doesn’t matter. He thinks her turns of phrase and amusing (to him) Cold War Russian-ising of words, eg “Whatski?” are her own, little realising that this is argot developed over a long marriage.

He enjoys the sex, even though he knows very little about sex and it seems Susan knows even less. Barnes has it that Paul is surprised that Susan hasn’t yet gone into menopause, which she refers to as The Dreaded. This small point strikes a false note – menopause, i.e. The Change, was a well-kept secret in the mid-twentieth century. Women did their best not to mention it within male earshot. It is unlikely that a 19 year old bloke with no interest in things medical would know anything about menopause at all, just as, when he offers help with a newly bought Dutch cap and contraceptive jelly from London chemist, she tells him “there are some things it’s better for a man not to see. Or to think about.”

Eventually familial and village scorn is enough to compel the lovers to run away to London, where Paul studies to become a solicitor so that he can keep Susan in the manner to which she is accustomed. They are in and out of one another’s lives, mostly destructively, for the next 14 years.

The story Barnes tells is compelling, even though it’s not really the story itself that concerns him. He is more interested in the way we remember the most important, life-changing events and relationships, and how we tell other people about them: “If this is your only story, then it’s the one you have most often told and retold, even if – as is the case here – mainly to yourself. The question then is: do all these retellings bring you closer to the truth of what happened or move you further away?”

Most would say the latter. We believe what we want to believe, and if a story contains some unpleasant truths or hard facts we would rather not confront, then after so many tellings those aspects may be dropped.

The Only Story is not a museum piece, a glass case displaying English life 50 years ago. After all, it is de rigueur these days for men to have an ancient partner. Macron was 15 when he first fell in love with Brigitte Trogneux, who is a quarter of a century older than he is. Joan Collins’s fifth husband is more than 30 years younger than her. Various internet sites extol the virtues of the older woman: she’s got money, she doesn’t want kids and apparently she’s grateful for the male attention.

Other contemporary concerns rise to the surface of the narrative, for example the current euthanasia debate. Susan remembers a doctor coming to visit her father-in-law, a lung cancer patient writhing with pain. The doctor told him, “It’s time to put you under, Jack.” The grateful patient was well aware that the doctor would put him into a morphine coma from which he would not emerge. This was common mid-twentieth century practice.

Barnes also takes a hard look at alcoholism of the female variety, which is an ever-increasing problem in Britain just as it is here. He refers to statistics that prove that the partners of alcoholics “despite being repulsed by the habit – frequently succumb to it themselves”, and how in the common view “…female alcoholics, old enough to know better, old enough to be mothers, even grandmothers – these are the lowest of the low.” Paul’s struggle to deal with Susan’s drinking is heart-wrenching.

Towards the end of the novel, Paul muses that “…there are metaphors which sit more powerfully in the brain than remembered events.” Julian Barnes is, after all, a literary novelist, and he puts some highly original metaphors to good use. Oddly, wrists are one of them – Paul plays a “wristy” game of tennis, ie good with both forehand and backhand. He likes to hold Susan by the wrists when they have sex, and later in life, to restrain and try to get through to her. He has a recurring dream of holding Susan by the wrists out a second-floor window. Perhaps Barnes is teasing us – we notice the wrist metaphor, but we have no idea what it means. One for the book clubs, perhaps. Shackles? Pulse points?

“I’m not trying to spin you a story; I’m trying to tell you the truth,” Paul reminds us, the same sentiment expressed several times in different words through the book. He also says that “in love, everything is both true and false; it’s the one subject on which it’s impossible to say anything absurd.”

When the older Paul finally steps out of the shadows, wiser and sadder, ex-solicitor turned artisan cheese-maker (another metaphor?) he has a memory of a long ago conversation with Susan about her friend Joan. He remembers Susan saying, “We’re all just looking for a place of safety. And if you don’t find one, then you have to learn how to pass the time.”

Time is a quality Hampstead novels always seem to have plenty of. Oodles of it. It’s one of the reasons we still read them, for the sense of an unendangered, unhurried way of life. If The Only Story seems at times facile, a story of first-world privilege, it also resounds deeply with masterful meditations on the meaning of love and sex between men and women.

The Only Story by Julian Barnes (Jonathan Cape, $35) is available at Unity Books.