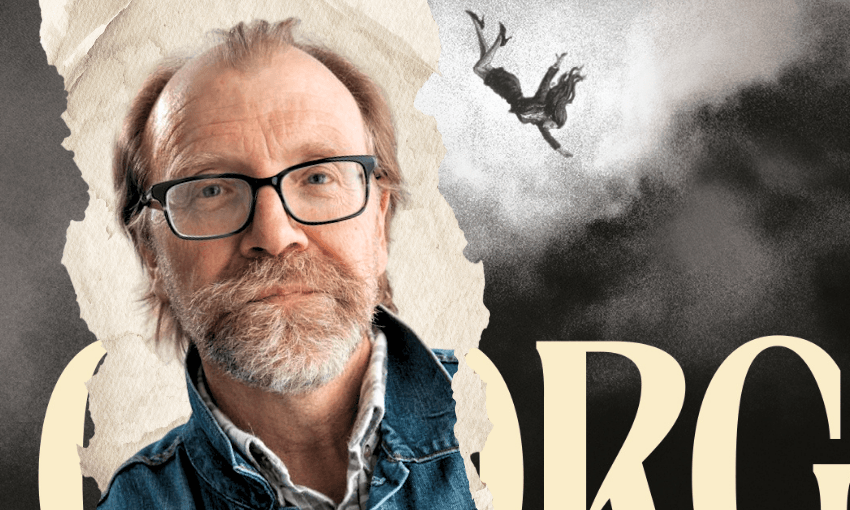

George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo is the year’s most talked-about novel, and there’s much excitement that the author will appear at the Auckland Writers Festival in May. Wyoming Paul reviews what may be a masterpiece.

A year into the Civil War, a tormented President Lincoln visits his 11-year-old son’s crypt in the cemetery. He holds his boy’s body one final time. His son Willie’s spirit is also present, tethered to the world of the living, out of longing to see his father again. The cemetery is populated by hundreds of other spirits, colourful and strange characters, who have refused to move on.

At its simplest level, Lincoln in the Bardo is a compassionate depiction of Lincoln at the most difficult time of his life – mourning his young son, while conducting a bloody civil war. But it’s also a meditation – a dark, comical, deeply empathetic meditation – on the universality of suffering, and the acceptance of dying with regrets and unfulfilled hopes.

Saunders mixes these daunting subjects with humour and a wonderful quirkiness. The introduction of Willie Lincoln, for example, occurs when one of the spirits, Vollman, is talking about the involuntary poop he did in his funeral clothes: “I hope you do not find this rude, young sir, or off-putting, I hope it does not impair our nascent friendship – that poop is still down there, at this moment, in my sick-box, albeit much drier!”

Combining that, flawlessly, with President Lincoln’s profound sorrow and a poignant understanding of the human condition…well, it’s quite something.

Willie Lincoln and the many spirits who remain in the cemetery are existing in a purgatory, or “bardo”, meaning the state between life and death. They are both unwilling to leave the world – and unwilling to accept that they have died at all. Almost all go to extreme lengths to believe that they might one day recover from whatever illness they have, referring to their coffins as “sick-boxes” and their corpses as “sick-forms”.

The spirits manifest with awful and often ridiculous deformities, each a symbol of their greatest connection to the living. Vollman, who died on the day that he would have consummated his marriage, presents with a limb-sized erection; a former hunter sits with the huge pile of animals he’s killed, holding each one in turn for hours or months until they come back to life; a woman who was a slave has feet and hands worn down to bloody stumps.

Saunders’s narrative is experimental and brave, written from the constantly changing perspectives of the spirits in the cemetery, all who are weird and fascinating, and difficult not to adore. We hear a cacophony of stories, all wanting to be told – of black slaves, soldiers, young women, a reverend, mothers, murderers, a rape victim – and can’t help but love (almost) all.

Other sections are composed entirely of beautifully arranged snippets from primary and secondary sources, describing aspects of Lincoln’s life – the ugliness or handsomeness of his face, whether or not the moon shone on the night of the Lincolns’ party while Willie lay burning with typhoid fever upstairs. Throughout, the novel moves easily between Saunders’s bizarre dark humour and the deep suffering of the characters, both those who existed and those who are fictional.

While those who died as adults can endure in this in-between world, Willie and other children cannot. Much of the progress which happens throughout the novel revolves around the spirits attempting to help Willie move on – while Lincoln is also attempting to reconcile his son’s death with the war he has declared, where thousands of other sons are being killed.

With Lincoln in the Bardo, Saunders has achieved nothing less than expanded the form of the novel. He’s knitted together history and fiction, and combined profound insights on human suffering with bawdy, rude, and comical narration. He’s created an American Civil War novel which is actually fun. Perhaps it could have done with a stronger female voice. But, my god – this is a rare achievement, a work of art.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders (Bloomsbury, $33) is available at Unity Books.