Contrary to many assumptions, New Zealand’s economic response to Covid was among the worst in the world in terms of widening wealth inequality and the wasteful use of taxpayer funds, argues Bernard Hickey.

This is an edited version of a post first published on Bernard Hickey’s newsletter The Kākā.

Since the onset of Covid in March 2020, the government of Aotearoa has delivered one of the biggest fiscal and monetary policy responses in the OECD in terms of taxpayer money spent and central bank money printed, relative to GDP. It also unleashed the strongest economic recovery, the fastest asset price inflation, and delivered the lowest unemployment rate in the OECD.

Surely that’s all good? The Labour government certainly paints its response as a kind and progressive one that has not left the most vulnerable behind. It has touted the success of its wage subsidies and regularly highlighted the various dollops of funds paid to food banks and for emergency housing and special needs grants.

But what was the scale of the support, and who is better or worse off as a result? The headlines look good, but what are the bottom lines?

The effects now evident in asset values and bank accounts nearly two years after the outbreak are simply astonishing. They show asset owners, who have been the beneficiaries of almost all the government’s direct support and central bank actions, are now astoundingly more wealthy.

Working families and beneficiaries who pay rent are now mostly worse off or barely treading water since the first lockdowns in March 2020. Food banks are seeing record demand and the waiting list for public housing has risen 65% to 24,475 since the beginning of Covid. It has trebled in the last three years.

The rich’s wealth rose by 50%

In short, by my calculations from Reserve Bank figures on term deposits, household financial assets and house and land valuations, asset owners’ wealth is on track to rise by $872 billion or 50% to $2.63 trillion within two years of the outbreak, including:

- a $45b increase in cash in bank deposits to $319b, which incorporates a $21b rise in non-financial bank deposits to $110b and a $24b increase in household deposits to $209b;

- a $608b increase in housing equity due to a $648b rise in the value of houses and land to $1.74t and a $40b rise in home loans to $318b; and,

- a $257b increase in the value of shares, bonds and other non-bank financial assets to $954b.

All of that increased wealth and cash on hand is due to government payouts and the actions of central banks here and overseas. Yet the money keeps flowing to those who already have it.

Here’s another chunk of change

The government announced last week that it would pay up to another $490m of cash grants to business owners as a transition payment going into the traffic light system, extending taxpayer support for the owners of capital and assets to a total of $20b in cash since the onset of Covid.

Just to be clear: wage subsidies were not paid to workers. They were paid to business owners to offset the wages of the employees they would otherwise have made redundant, although that willingness to fire staff or the ability to use their own existing buffers was never tested.

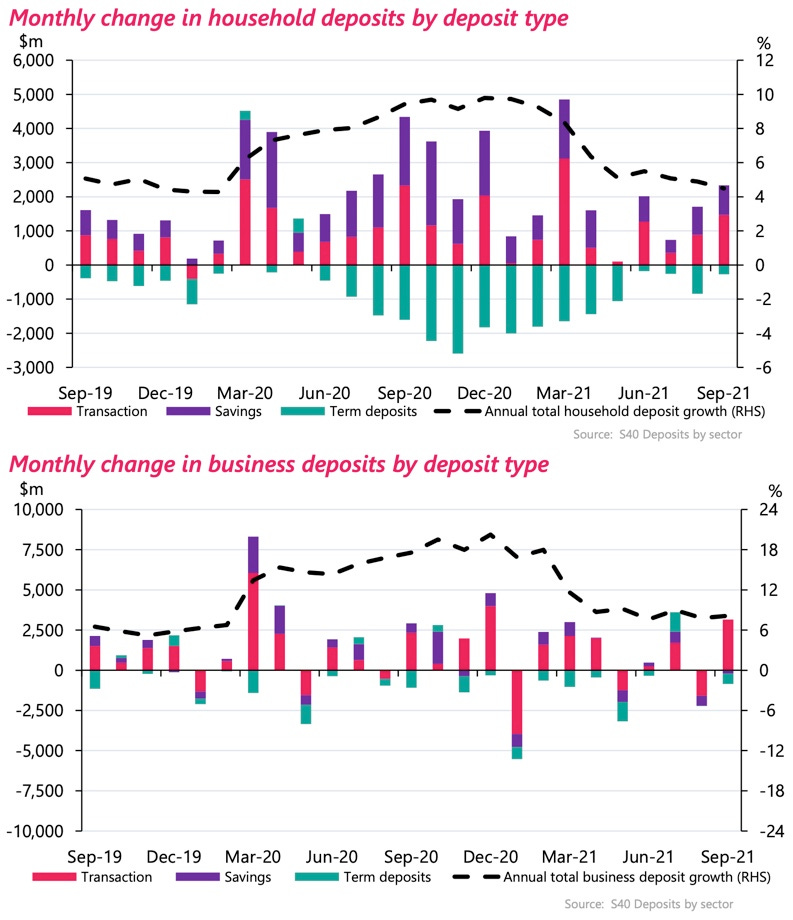

Meanwhile, the cash balances of transaction and term deposit bank accounts of non-financial businesses and households owning property have risen by a net $45b since Feb 2020 to $319b at the end of September. Significant increases in cash deposits can be seen in March and September soon after the government payments, and have continued increasing since then.

None of the wage subsidies, resurgence payments or the new transitional support payments were ever means tested or given as loans for repayment. An assumption was made in March 2020 that there was not enough time to check and business owners needed a shot of confidence to keep employing people. Somehow, that assumption was not challenged or revisited in August 2020 or August 2021 when fresh resurgence payments were made, even though the experience after March 2020 was of quick economic and spending recoveries, and a strong labour market.

Why no means testing or clawbacks?

There was never any suggestion of clawing it back if, in the event of a strong recovery, businesses ended up with cash surpluses, which is indeed what happened.

The desperate situation forecast in March 2020 of double-digit unemployment meant the first handouts of cash labelled as wage subsidies were forgiveable and certainly worked spectacularly to stabilise the situation, largely due to the speed and lack of conditions with the cash.

But it was clearly abused in retrospect, and then the government failed to follow up and pull back funds through the end of 2020. By then the government had given $14b in cash to businesses and less than $1b had been paid back. MSD did not even send letters to businesses asking them to check if they had indeed needed the money and whether they should pay it back. Auditor general John Ryan has criticised the MSD’s lack of proper audits and follow-ups with subsidy recipients.

Many companies, including Hallensteins Glassons, Fletcher Building, Harvey Norman, the James Pascoe Group (Pascoes the Jewellers, Stewart Dawsons, Goldmark, Whitcoulls and Farmers), NZME and Fulton Hogan took the cash and did not repay any or all of it, even though they quickly returned to profit and are again paying dividends to shareholders.

Some refused to pay the money back on both sides of the Tasman, including Michael Hill Jewellers, Kathmandu and Harvey Norman. Then there were the luxury product and services businesses, often owned by rich-listers, that took the money and never repaid it, including The Wellington Club, The Northern Club, the Kauri Cliffs golf course and the Millbrook resort and golf course in Queenstown. The luxury lodges, wineries and golf courses owned by US hedge fund billionaire Julian Robertson claimed more than $1.2m in subsidies and didn’t return them, despite making hefty profits by the end of the year.

Some were embarrassed into repaying

Some businesses were effectively shamed into repaying their wage subsidies through mid-2020, including The Warehouse, Briscoes, Ryman Healthcare and Vector. Others hastily repaid the money slightly earlier when they realised their customers, staff, regulators and competitors could find out here the names of which large companies were paid and how much. There were some embarrassingly high-end names who had to scramble to give the money back, including blue-chip law firms such as Bell Gully, Simpson Grierson, MinterEllisonRuddWatts, Meredith Connell and Lane Neave. Some, including the private equity-owned and heavily-indebted Trade Me only repaid after revolts from embarrassed staff.

So far, only one reported prosecution has been launched by MSD against those who took the money without justification, out of over 1,000 cases referred for investigation. During that time, MSD has launched dozens of prosecutions against beneficiaries.

Various advisers, including in a detailed report from the auditor general’s office, recommended someone in the government simply ask those who received cash to prove with GST receipts that they needed the money and if not, repay the money. Neither has happened. There has also never been proper audits of how the money was sent, used, and not repaid. Newsroom’s David Williams, who has been doing some excellent reporting on this, reported earlier this month that MSD had asked for about $6.8m of repayments from the 10 largest companies it had requested repayments from.

Meanwhile, here’s the list compiled via Newsroom of the top 30 recipients of wage subsidies, who received a total of $842m, most of who are large overseas-owned or listed companies. Newsroom reported last month that MSD had done sample checks on 339 of the 396,817 businesses that received the subsidy last year.

Not nearly as much for the working poor

The biggest losers in the Covid recovery have been those in itinerant work or piecemeal work, who have lost income, along with those renting. Last year those on benefits and the working poor received benefit increases that were not enough to cover rent increases. Last year they received a doubling of the winter energy payment, but not this year.

The government announced earlier this month it would lift the incomes of 346,000 families by an average of $20 a week with various increases in best start payments and higher tax credits, but only from April next year. The PM said it would lift 6,000 children out of poverty. It is costing $68m a year for the next four years. Just imagine what $20b worth of cash paid to increase benefits, let alone to invest in housing and infrastructure, would have done to reduce child poverty.

Last month, MSD minister Carmel Sepuloni announced an extra $9.6m in hardship assistance for low income workers, although some of it can be clawed back at a later date.

Child poverty activists have described the recent one-off grants and tax credits, some of which are clawed back as recipient incomes rise, as disappointing and out of touch.

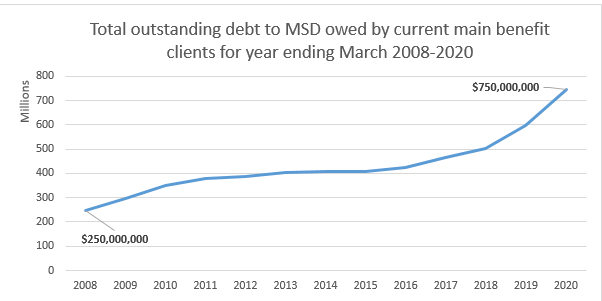

That has been reflected in massive increases in demand for food parcels and a rise in debt owed by beneficiaries to MSD. As of March 2020, 67% of beneficiaries owed an average of $3,600 in debt to MSD, with debt rising $150m to $750m in the year to March, 2020. The Govt has rejected suggestions of an MSD debt moratorium or writeoff.

So in summary…

Due to government policies for cash payments and money printing to create a wealth effect and rescue the economy and jobs:

- the wealthy were made $872b richer, largely because of a 54% rise in house prices forecast in the two years (the RBNZ sees another 10% rise over the next year) after the onset of Covid;

- the government will have given at least $20b in cash to business and asset owners in a period when those asset owners have increased their cash savings accounts by $45b to $319b;

- the even-wealthier recipients of those cash grants have largely refused to repay the money, even though it is considered normal for the recipients of benefits to repay money deemed not necessary to overpaid; and,

- workers and beneficiaries who rent are worse off because of part time and extra hour job losses, along with rent increases and inflation in costs of petrol and food.

Yet many boards and leaders talk about ‘Building Back Better’ and just transitions. Some have even said workers should be grateful for low unemployment and that the measures taken have made New Zealand a model for the rest of the world.

A counterproductive erosion of social cohesion

One feature of the double standard when it comes to the double standard described above is that the poor notice – and, understandably, can sometimes be uncooperative when the government needs them to do something for society as a whole. Such as get vaccinated.

Essentially, the social contract is broken.

The clearest sign of that inevitable loss of social cohesion can be seen in low vaccination rates, which are closely aligned with the most deprived and vulnerable suburbs.

When business leaders and asset owners express surprise and disappointment when poorer voters and citizens are uncooperative or vote for the ‘wrong’ candidates, they should look first at whether they seriously think the last two responses by government to crises were just and effective.

The strategy of bailing out businesses and making the wealthy wealthier has worked for the wealthiest during the GFC and Covid, but it has further deepened the societal divisions in the process, storing up yet more social and political conflict for the next crisis.

Follow When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey’s essential weekly guide to the intersection of economics, politics and business on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider