Analyst Emma Vitz turns her gaze to renting data, discovering that New Zealanders are spending twice as much as they did 30 years ago to live in increasingly squalid houses.

Renting in New Zealand is often considered a temporary stopgap on the way to home ownership. Some see it as an uncomfortable phase that young people put up with for a couple of years while they save for their deposit, along with two-minute noodles for dinner and wearing a sweatshirt to bed to avoid turning on the heater.

But the reality is that in 2018, 35.5% of New Zealanders did not own their own home, a number that has been increasing since the 1980s. Renting is no longer exclusively the domain of younger people. Over 31% of those aged 65 or older do not own their own home, and this percentage has increased for every age group since 2006.

With this in mind, I wanted to have a look at how the affordability of rentals has changed over time. Once again, I took the common financial rule of allocating 30% of your gross income to housing and calculated how much a household would need to earn to afford the average rental going back to 1993.

The prices were inflated to current dollars using the consumer price index in order to make them comparable to 2021 figures. I used rental data from Tenancy Services. This data includes all rentals in New Zealand, from studio apartments to large family homes. I assumed that the average would represent a mid-sized home in New Zealand.

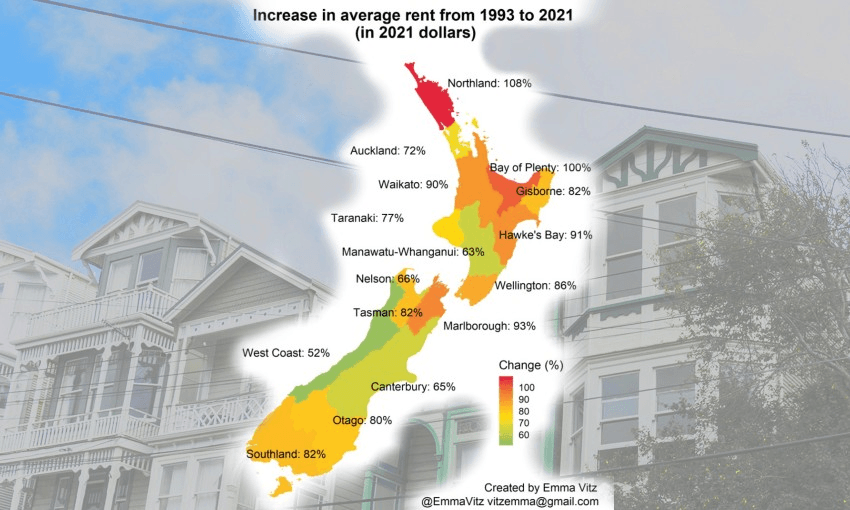

Across New Zealand as a whole, the cost of renting has almost doubled in today’s dollars since 1993. In 1993, an income of $45,856 in today’s dollars was required to afford the average rental. Today, that figure is $84,059. In relative terms, Northland has seen the highest increase in rental prices with an increase of 108% in current dollars. Other regions like the Bay of Plenty and Marlborough have seen sharp increases as well.

Given that more and more people are renting for longer, and that rent prices have increased substantially over time, we might expect the quality of rentals to improve.

However, the Wellbeing statistics show that housing quality differs substantially between renters and those who own their own home.

In 2018, 36% of renters said their house was always or often too cold, compared to only 15% of those who owned their own home. Similarly, 49% of renters said their house was sometimes or always damp, compared to 27% of owners. Of the 47% of renters who said their house was mouldy, 56% said the mould was larger than an A4 piece of paper. This compared with 30% of owner-occupiers having a mouldy house, of which 37% said the mould was larger than an A4 piece of paper.

These numbers are an indictment of the overall housing quality in New Zealand, but they also show that renters are more likely to experience the worst of these conditions. And these renters are not exclusively students who can look back and laugh about the time a whole window fell off its hinges in the middle of the night, letting the howling Wellington wind in (it happened to me). Increasingly, they are families and even retired individuals, for whom renting is the only long-term option.

Emma Vitz is an actuarial analyst for Finity Consulting. The opinions expressed in this story are her own and do not represent those of her employer.

Follow When the Facts Change, Bernard Hickey’s essential weekly guide to the intersection of economics, politics and business on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.