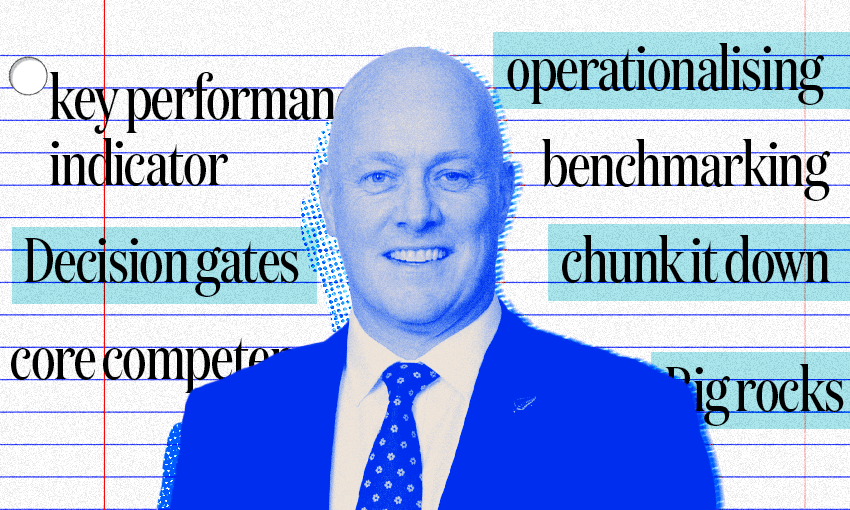

An operationalised, strategically aligned, actionable guide to the phraseology of prime minister Christopher Luxon.

The prime minister loves business jargon. Luxon’s 36-point action plan is full of pledges to “take decisions” and “raise the energy”. But his media team is slowly beating that instinct out of him, and it’s a real shame.

It’s cute seeing Luxon embrace his true self. Corporate speak makes him feel comfortable, it reminds him of his young, carefree days at the University of Canterbury business school, where he provided operational efficiencies in beer pong and accelerated leveraged opportunities on the dancefloor.

Like all politicians, sometimes Luxon’s corporate speak is just word-salad. But sometimes, our prime minister is actually trying to communicate with us. He just forgets normal people don’t spend their spare time reading books with titles like Seven Steps to Synergising Success because, well, they are normal people. It’s a sad sight, like a baby desperately trying to tell its parents what it needs, but it doesn’t quite have the words.

Out of pity, we compiled a guide to some of Luxon’s favourite bits of business school jargon, what they mean, and where he probably learned them.

Chunk it down

Example: “You still have to chunk it down and actually execute components on it.” – Luxon on government reforms.

Definition: To break a larger project or goal into smaller tasks.

Origin: Like most business school jargon, this sounds like a common-sense phrase that has probably existed forever, but Luxon almost certainly learned the phrase from the 2004 book The Success Principles: How to Get From Where You Are to Where You Want to Be by Jack Cranfield.

Big rocks

Example: “We need to elevate up and say, ‘Well, what are the big rocks and the additive things that actually the other parties are bringing to our agenda?” – Luxon on the coalition negotiations.

Definition: Big rocks are your priorities. It’s part of an analogy about filling a jar with rocks. If you put the big rocks in first, you can still fit the smaller rocks around them. But if you fill it with small rocks first, you’ll never be able to fit the big rocks.

Origin: The big rocks analogy was popularised by the 1989 self-help book The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey.

Deliverables

Example: “We are looking ahead to actually deliver a set of deliverables that will help our vision of New Zealand to take root and come to pass.” – Luxon’s instructions to his MPs at their 2024 annual retreat.

Definition: Deliverables are the things that must be delivered throughout a project. It includes the final product, but also things like reports, updates and prototypes that need to be prepared along the way.

Origin: One of the earliest examples of the term is from the Work Breakdown Structure, a “deliverable-oriented” method of project management developed in 1962 by the US Department of Defense.

Operationalising

“We are operationalising our government.” – Luxon, on operationalising the government.

Definition: No, it doesn’t just mean making the government operate. In science, operationalisation means to take a vague concept and try to define it with measurable observations. For example, personality differences are vague, and the Meyers-Briggs test is an attempt to operationalise them. In business and government it’s about trying to create standardised, repeatable processes even for big, vague goals (like getting our mojo back).

Origin: The idea of operationalism was coined in the 1927 book The Logic of Modern Physics by Percy Williams Bridgman, and eventually spread to the social sciences and business schools.

Core competency

Example: “We’ve got to focus on what our core competency is and what our advantages are and what we can actually do to help.” Luxon, on New Zealand’s involvement in the war in Ukraine.

Definition: The attributes that make a person or company stand out from the competition. For example, Luxon’s core competencies are his business experience and saying words like “core competencies”.

Origin: First used in the 1990 book The Core Competence of the Corporation by C.K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel.

Value chain

Example: “We don’t generate enough value from what we do because we can’t get ourselves up the value chain to generate higher-value products and services.” – Luxon, on the quality of education in New Zealand.

Definition: The value chain is the process by which a raw product becomes more valuable and therefore more profitable. Chopping down a tree is at the bottom of the value chain. Then, someone adds value by cutting it into timber, and someone else creates even more value by turning that timber into a house.

Origin: The term “value chain” was first introduced in the 1985 book Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance by Michael Porter.

Results-driven

Example: “The coalition government will make decisions that are… results-driven. Interventions that aren’t delivering results will be stopped.” – Coalition agreement between National and Act.

Definition: Managing an organisation based on achieving outcomes, rather than being overly focused on adhering to strategies or processes.

Origin: The concept of results-driven management is most often credited to the 1954 book, The Practice of Management by Peter Drucker, though he referred to it as “management by objectives”.

Benchmarking

Example: “A big part of that is to know whether you’re actually benchmarking your performance and knowing whether you are or are not hitting the mark and doing the right thing.” – Luxon on whether councils should have to do audits.

Definition: To set a specific standard that you can be measured against. It might be better for a business to benchmark itself against its competitors, rather than just looking at overall sales.

Origin: A benchmark was originally a form of survey marker, chiseled in stone to form a bench for a levelling rod, so the measurement could be accurately repeated in the future. It reached the business world in 1979 when Xerox undertook benchmarking studies to compare itself to its competitors. It was popularised by the 1989 book Benchmarking: The Search for Industry Best Practices that Lead to Superior Performance by Bob Camp.

Key Performance Indicators

Example: Luxon has publicly said he would set KPIs for other National Party MPs.

Definition: KPIs are commonly used in the corporate world to measure whether an employee is doing a good job, especially if their work can’t be directly linked to a financial result.

Origin: Key Performance Indicators as a concept have existed for basically all of human history, but the phrase was popularised among business nerds by the 1996 book The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action by Dr. Robert Kaplan and Dr. David Norton.

Mission creep

“Fundamentally, there has been mission creep with the Reserve Bank.” – Luxon on the Reserve Bank’s dual mandate.

Definition: Mission creep refers to when an organisation’s mission becomes broader and vaguer over time, until they lose sight of what they were originally meant to be doing.

Origin: The first recorded use of the phrase is in a 1993 Washington Post column by Jim Hoagland about the battle of Mogadishu – “Beware ‘mission creep’ in Somalia“. It quickly became a common phrase in the military and business world.

Decision gates

Example: “You take those big topics and you chunk them down by decision gates as well through the quarter.” – Luxon on his second quarterly action plan.

Definition: Decision gates are part of a model of product development called the Stage Gate process. It breaks down the process into five phases, from idea to launch. Between each phase is a “gate” where you have to decide whether to continue the project, modify or scrap it.

Origin: First introduced in the 1988 article Stage-gate Systems: A New Tool for Managing New Products by Robert G. Cooper.

Gates of implementation

Example: “It’s just making sure that as we go through the gates of implementation of different decisions that we’re taking, that we’re actually consciously working, moving forward.” – Luxon on his government’s action plan.

Definition: Once you have passed through the decision gates, I guess there are another set of gates where you implement things?

Origin: Gates of implementation does not appear to be a thing. As far as I can tell, no one has ever said these words before. Is this the title of Christopher Luxon’s future business bestseller?

This dictionary will be updated as new vocabulary is introduced.